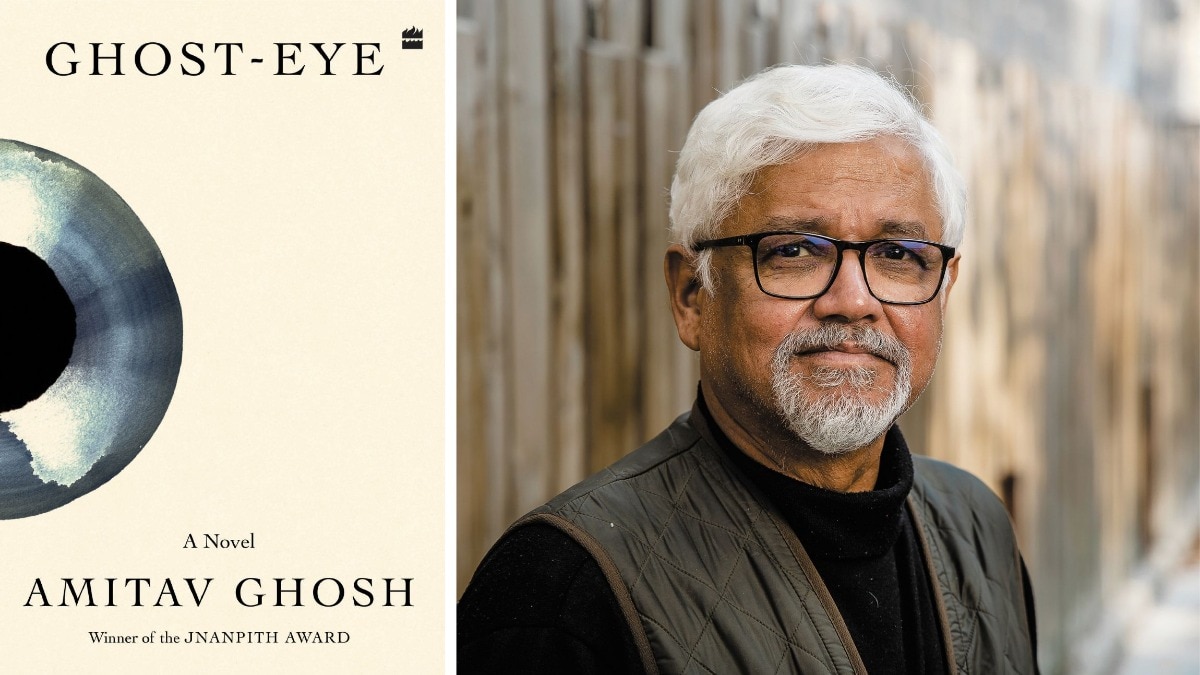

Inside the minds of India’s next-generation art collectors

With all eyes on India, five new-age collectors reflect on their journeys of patronage that extend beyond private collections toward lasting cultural legacies.

What does it mean to be an “art collector”? This was the fundamental query that guided my conversations with five young collectors from across the country. Over several hours spent on Zoom meetings and phone calls, my rudimentary assumptions about what often appears to be an extravagant pursuit were quietly dismantled, revealing an informed and intentional engagement with art and artists through personal patronage, institutional support, and the primordial impulse to surround oneself with beauty.

The collectors express a critical negotiation of the acquisitory epithet, adding layers of nuance and depth to the act of collecting. There’s an overwhelming sense of “why” that defines our exchange, and it is here that the power of these stories lie. As South Asia positions itself as one of the leading talent pools and global markets, these new-age collectors are looking beyond building personal collections. Instead, they are contributing to a broader cultural landscape, shaping artists’ careers, expanding public access to art, and participating in the stewardship of artistic legacies.

SIDDHARTH SOMAIYA

“Artists are knowledge creators, they aren’t just decorating something to match your couch,” says Siddharth Somaiya. For the Mumbai-based educator, entrepreneur, and co-creator of the IMMERSE Residency & Fellowship at Somaiya Vidyavihar University, artists lie at the nucleus of the ecosystem. “I don’t consider myself a collector, nor do I aspire to be one,” he clarifies. “For me, it’s not about consuming art, but supporting artists’ practices and lived experiences.”

Our conversation over the next half-an-hour is driven by Somaiya’s distinct sense of clarity and purpose. I feel compelled to comment on his eloquent efficiency with which he takes me through his journey as a collector— as tenuous as his relationship with the label might be. To trace the origin of this need to render support, he recalls how as a young boy he watched his grandfather, Dr Shantilal K Somaiya, bring home Kashmiri carpet sellers, artists of Pichhwai or contemporary miniatures: “I would watch him buy but never really display anything. He bought these pieces to support someone’s life, and subconsciously over time, I imbibed that too.” Somaiya believes patronage is one of the primary ways to bridge the early valleys of death in young artists’ careers. A predictable income becomes a career-defining axis, especially for artists from marginalised communities and non-urban peripheries.

As a patron, Somaiya is deeply invested in understanding an artist’s practice, the rigour of their thought and of their hand. “I want to see someone go through the struggle of communicating effectively,” he notes, emphasising the importance of an artist’s processual training in both storytelling and technique. To elaborate, he draws attention to Riya Chandwani, a young artist from Madhya Pradesh, who weaved her Sindhi family’s experience of Partition into her work, expressing a collective history and memory of displacement and trauma. As a powerful and resonant manoeuvre, Chandwani placed mud from her ancestral homeland in Sindh next to her work. “When I was supporting her practice, I was also supporting a nation’s bookmark in time, whose effects continue to be felt today,” Somaiya observes.

When faced with the impossible task of picking favourites from his collection, he chuckles that he could easily give me a list of 50 names. While his family collection is rich in antiquities, Somaiya’s collection is composed of emerging artists, stitching together past heritage with present moment.

He does draw my attention to two works in particular by an IMMERSE Resident, Anila Kumar Govindappa. Born to a labourer in Karnataka, Govindappa’s work, Mother’s Dream, is a visual invocation of his mother’s dream to own a home. With his mother sleeping on a cloud in one corner, the painting depicts a beautiful walled home and an excluded family in what appears to be a forest. Three years later, Govindappa painted a sequel: this time, he is seen hurrying his mother and wife into the home, punctuated with a declaration of an “I love you”. This symbolic crossing over the wall is the impetus behind the IMMERSE Residency and Fellowship, which offers a platform to bridge dreams and reality.

Somaiya’s practice as a collector is intricately tied to offering an all-encompassing package of support to artists. “In art school, they teach you how to make art. We want to teach them how to be an artist,” he says. Speaking to him even briefly makes you acutely aware of his conviction to work towards something much bigger than amassing a private collection. His advice to young art collectors is laced with a similar temper: know yourself before you acquire art; more importantly, know the artist, visit their studios, and truly understand their practice. “You learn so much more about yourself— what moves you, what motivates you—through the lens of an artist,” he concludes.

NUPUR DALMIA

“I always say that art kind of happened to me,” beams Nupur Dalmia, as the late afternoon sun casts a warm glow across her room during our Zoom call. With an educational background in English and Political Science from the University of California, Berkeley, an MBA from the Indian School of Business, and experience in tech marketing, Dalmia’s career has followed an unconventional trajectory. She now serves as the Managing Director of the Ark Foundation for the Arts in Vadodara, a collaborative institution that focuses on expanding the scope of public engagement, pedagogy, and archiving of artistic histories. Dalmia’s practice as a collector is deeply intertwined with an institutional collection: the Ark Museum Baroda, set to open in 2029.

The Foundation was preceded by Gallery Ark, founded by Dalmia’s parents, Seema and Atul Dalmia, in 2017, which served to offer patronage and address the lack of formal spaces for exhibition in the city. Dalmia stepped in, without an art history degree or curatorial experience, yet equipped with a keen sense of curiosity and a proclivity for learning on the job. The decision to establish a museum was rooted in her interest in histories, friendships, narratives of progression, the life story of Baroda, and critical discourse on art. “Art is the most natural inclination and people need points of entry,” she qualifies. “It’s about the zeitgeist. It’s for everybody.”

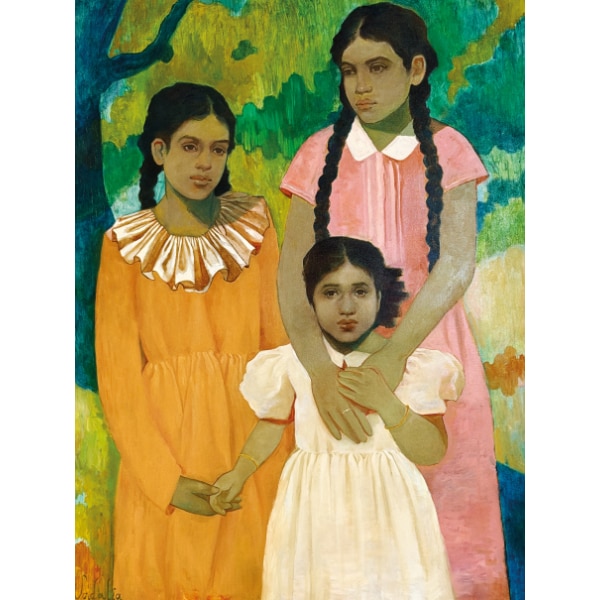

Dalmia’s art collection is guided by the larger vision for the Ark Museum Baroda to depict post-Independence developments in South Asian modern and contemporary art, using the city as a historical lens. “The Faculty of Fine Arts at MSU Baroda started right at the heels of Independence, repositioning visual art from a vocational skill to an intellectual pursuit as well,” she notes, highlighting the influential role of the institution and the city in shaping India’s art landscape.

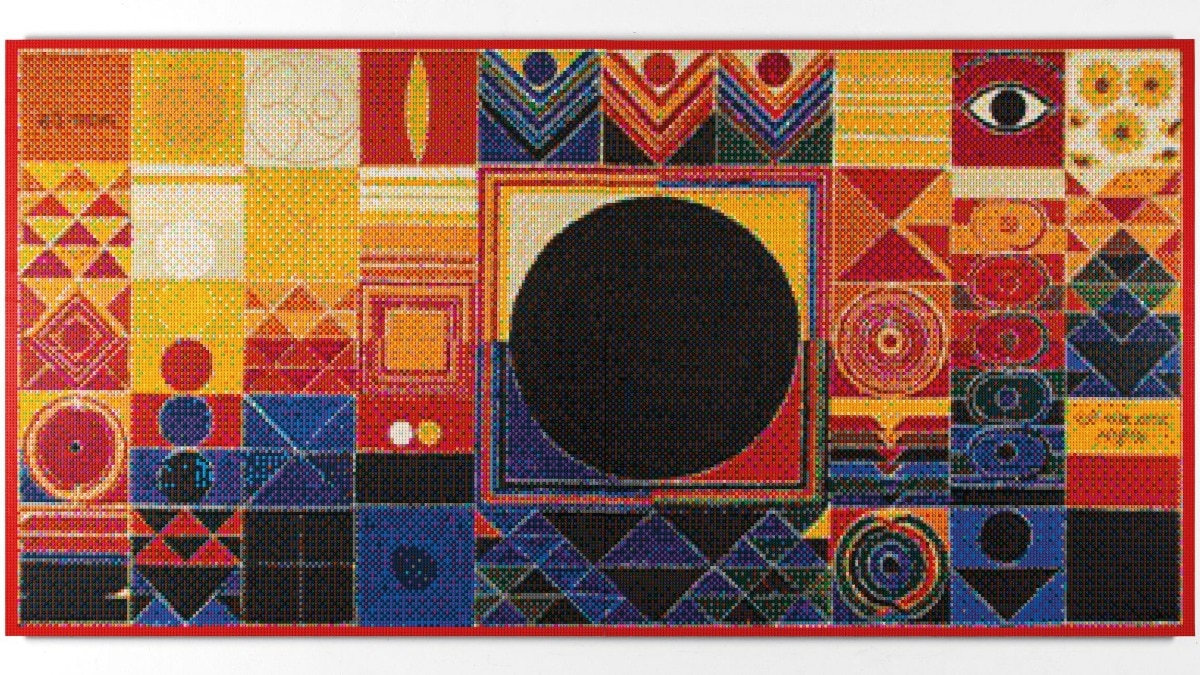

Dalmia began acquiring art for the museum in 2021, mindful of the scale of responsibility. The collection boasts representative bodies of work by several important figures in Baroda’s oeuvre; she particularly acknowledges KG Subramanyan, Jyoti Bhatt, Nasreen Mohamedi, Nilima Sheikh, and Gulam Mohammed Sheikh, among others. When it comes to collecting young artists, she expresses a critical awareness vis-a-vis the museum’s prerogative to make canonical propositions. “As an institution, what we put out is saying something. You don’t know how it will be received, but the awareness matters,” she states. The favourite part of her job is visiting artists in their studios and learning about their practice. She adds, “I never acquire their works without engaging with it extensively. It’s not just rewarding, but equally addictive. Additionally, as a public collector, personal liking is not enough. I need to back my choices with context.”

She points to the work of artist Mahesh Baliga, whose works represent living traditions in today’s context. “I see ‘life’ as it is in Mahesh’s work, life that exists in real-time, the life that one often overlooks in reality. His practice is a great example of what I informally call “Baroda plus plus”—it is, for instance, one example of why Sudhir Patwardhan or Gieve Patel are part of the museum’s narrative. Also clearly evident are the influences of others, such as Bhupen Khakhar and Subramanyan,” she elaborates.

Wrapping up our call two hours later, Dalmia has some advice for young collectors building their personal collections. “Don’t buy everything you immediately fall in love with, but don’t buy anything you don’t immediately fall in love with either.” The sun has set by now and I’m struck by the generosity she affords me with her time— it’s indeed a quiet extension of the artistic largesse required to imagine a museum from the ground up.

RHEA KURUVILLA

One never truly owns a work of art, believes art advisor and collector Rhea Kuruvilla. “At most, we are stewards and custodians.” Kuruvilla started her career as an art marketing professional at Saffronart, India’s leading auction house for modern and contemporary South Asian art. She was then a part of Art Mumbai’s founding team. Currently, she serves as the VIP Consultant for India at Frieze. Raised in Mumbai by parents who were collecting art through the years, Kuruvilla also grew up amongst a constant stream of artists, writers, designers, and musicians who visited her home.

“My love for art started with the love for objects,” she notes, reflecting on her time living in Milan and London, where she’d go perusing the local markets every weekend in search of vintage and one-of-a-kind collectibles. Her interest in collecting grew as a natural extension of her environment. When friends began turning to her for advice on shaping their collections, she found deep fulfilment in sharing the joy of collecting, leading her to formalise her advisory practice. As an advisor and collector, she strikes a careful balance between passion and precision, the emotional pull of a work and the knowledge that contextualises it in history and the market.

“I’m instinctively drawn to works that carry a certain charge, a raw energy, something that’s slightly off-centre,” she says. With time, she’s evolved in her response to different works, now informed by other factors such as the artist’s trajectory, their practice, and public and institutional collections they are a part of, amongst other considerations. What hasn’t changed is her purpose: for Kuruvilla, collecting art is not a liquid investment, and every decision needs to have heart in it. That’s a non-negotiable.

She’s also a strong believer in collecting works by young artists of our generation, to not only support the current ecosystem but also to preserve such works that act as an archive of our present. “It becomes a record of history, of time, an evolution of who you are, and becomes timestamps of memories,” she explains. In the same breath, she also advises young collectors against rushing to build a “serious” collection. Instead, she suggests identifying a couple artists whose work you genuinely enjoy and following them closely and supporting them through their journey. Try to understand what they are wrestling against, check in on new bodies of work, celebrate their milestones. A meaningful collection is built through this kind of slow, attentive engagement.

Following suit, Kuruvilla embarked on a spontaneous six-hour round-trip to Kolkata on her first virtual encounter with The Intertwining II by Indian-American artist, Bhasha Chakrabarti. “I was immediately drawn to its striking, layered work, which at first glance is charged and provocative, but ultimately unveils a quiet tenderness,” she observes. Another favourite is a terracotta sculpture by Australia-based, Sri Lankan-Tamil artist, Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran, that she considers to be a “fantastic wild idol that feels both ancient and radically contemporary.” But none come close to an untitled side profile by Gurusidappa GE that reminds the collector of her paternal grandmother she never had the chance to meet. “There’s a lot of her [grandmother’s] energy in this work from what my relatives have told me, so this is the only imagined connection I have with her,” she fondly reflects.

At present, with all eyes on the region, Kuruvilla is excited by the positive growth story within the South Asian art community. There’s a visible increase in access, accompanied by a simultaneous rise in education and exposure within both artist and collector bases. Working at the intersection of these worlds, Kuruvilla finds herself closely attuned to a moment of change unfolding in real time.

SALONI DOSHI

Saloni Doshi confesses that she’s not an easy collector to please. The arts patron and founder of the Space118 Art Foundation has been in the game for over 24 years—and it shows. Doshi’s journey as a first-generation collector began in the early 2000s as a solitary pursuit. “There’s not a single collector bone in the family,” she remarks on a bright sunny morning in Mumbai. “In fact, because we are Jain,” she continues, “there’s an emphasis on owning less, living with less. But I like to surround myself with beautiful things.”

For Doshi, coins and stamps in childhood graduated to textiles, wooden artefacts, and period furniture as an adult. While her first purchase was a poster of an Amrita Sher-Gil work, her collection now includes over a thousand acquisitions. After her Master’s in Media and Communication from the London School of Economics and Political Science, she joined The Times of India to digitise their publications. “I was living with my parents and had no overheads. There was no better utilisation of the money I was earning,” she reflects. Art, she says, brought her pure joy and satisfaction.

Doshi’s practice as a collector is guided by three rules: “I don’t buy dead artists, I only buy what suits my pocket, and I buy art that I want to live with.” Feeling takes primacy in her attraction to a work of art. Does it evoke happiness, sadness, discomfort? “I look for myself in the work,” she explains, as she roots herself in this moment of encounter— to buy an artwork, it must first deliver her to a state of presence, of being. This is a moment of knowing, of trusting one’s gut, both of which Doshi suggests can be developed over time. “Go to museums, galleries, biennales, and look at art, engage with artists,” she advises, “this is how you learn to assess with clarity.”

What should be a near-Herculean task, that is picking favourites from her collection, Doshi handles with casual ease. She instantly names Anju Dodiya’s 1998 painting Studio Guests. The pair of European visitors watching a trio of sword-swallowers is a work she finds deeply resonant. Equally prized is Zarina’s Delhi that was flown in from New York after quite a chase. The series represents a sense of loss for the city that the collector grew up in. “I never buy names, but if there’s a particular work I want, I will buy it, even if I have to buy it from an auction,” she adds. Meanwhile, Sonia Jose’s Self Portrait (with clothes pins) and T Venkanna’s Naughty Nighty in the Night fall on the eccentric spectrum of her collection, articulating beauty across diverse registers.

With the fifth show on view at Space118, titled The Presence of Absence, curated by Kunal Shah from Doshi’s collection, the latter is already living a collector’s long-held ambition. And beyond collecting and showing her collection, she has also been a serious patron of the arts since she established the foundation in 2009. The initiative was launched to provide studio residencies to young visual artists, and transitioned to a financial grant-making organisation in 2021, with over 450 residents since then. “I don’t want good talent to ever get erased because they lack financial backing. I want to support these critical voices, be it artists, practices, curators, or collectors,” she adds.

With a disclaimer of impending morbidity, I ask her if she’s thought about the future of her collection, beyond her time here. “The foundation shall outlive me, and everything I own shall be used to fund it,” she says, “I’m not married, I don’t have children, and I’m going to prove you don’t need any to create your own legacy.”

JAIVEER JOHAL

Jaiveer Johal, Chennai-based entrepreneur and founder of Avtar Foundation for the Arts (AFTA), is a self-confessed hoarder. “I’ve always collected things, and it’s not something entirely new to me as a person,” he laughs over our phone call. Even though he’s just hopped off an early morning flight, there’s an infectious lucidity in his voice as he offers me a glimpse into his life’s governing impetus to acquire things of beauty.

Johal’s propensity to collect found its initial manifestation in antiquarian maps and prints that he bought in London as a postgraduate student. Shortly after, he moved on to silver, and eventually settled on modern and contemporary art, which he has been collecting seriously for almost nine years now. “Growing up, my family bought things to fill up space—a wall here, a cabinet there—but there was never an intent to buy without knowing where to put it,” he remarks. His departure from the familial pursuit is marked by an acquisitory impulse. “Where decorating stops, true collecting begins,” he notes succinctly

Johal’s collection spans from paintings to textile and sculptures. “I’m agnostic to the materiality of collecting. It depends how the work speaks to me,” he states. His prebuying checklist is a simple one: “Do I like it? Can I afford it? If the answer is yes to both, I buy it.” But a meta-question lingers over us: when we like something, why do we like it? He underscores the various layers and complex processes that build up to the epiphanic moment of “I love it!” Borrowing the concept of navarasa (nine emotions) from the Natyasastra, the classical Sanskrit treatise on the arts, Johal argues that a work must first generate a rasa in him, whether it’s love/beauty, laughter, sorrow, anger, heroism, fear, disgust, wonder, or peace. But to enjoy the rasa, one must be a rasika, highlighting the importance of studying artists, their practices and their oeuvre. “This epiphany comes from a very serious process of seeing, reading, and listening. This is a moment of being more right than wrong,” he elaborates.

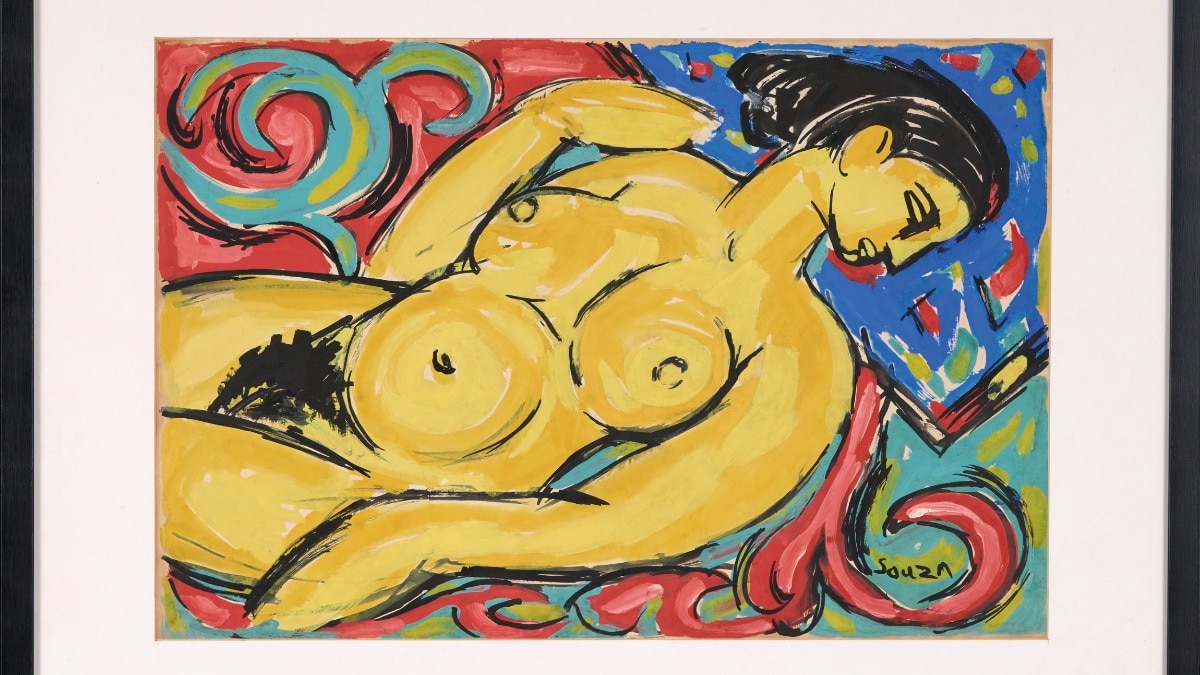

As most young art collectors tend to begin with building homes, Johal advises that you shouldn’t be afraid to live with an empty wall. Art collecting, he argues, is primarily the business of knowing what not to buy and saying no to mere space fillers. Similarly, a firm budget is crucial, but if opportunity arises, you shouldn’t shy away from blowing all of it on one work. One of Johal’s earliest acquisitions were works by Indian modernist painter, FN Souza, pop artist Bhupen Khakhar, and the iconic geometric abstractions of SH Raza. He also holds a special affinity for New York-based artist, Zarina, known for her printmaking practice. “Zarina is very important to me as an artist and a person. We share a very similar mind-space,” he adds. And one can’t help but mention the 200 kilogram concrete “Bhupen Bench” by Atul Dodiya in his collection.

In 2024, Johal established AFTA in Chennai, to address the lack of public or private patronage for modern and contemporary art in the city. “From the late 1970s onwards, Madras fell off the visual culture map in terms of paintings and sculptures,” he explains. The aim was to engage with ideas through curated shows and introduce audiences to broader streaks of development in the art world. The latest show, Udal: Reading the Body, was curated by Shruti Parthasarathy, in collaboration with Alliance Française of Madras. “The idea is that art is for everyone as long as you put in the effort to understand it,” Johal remarks, “to make things simple without making it simplistic.”

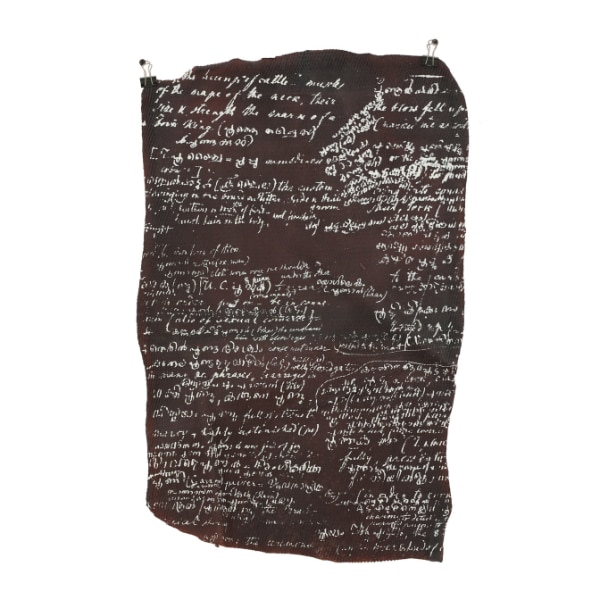

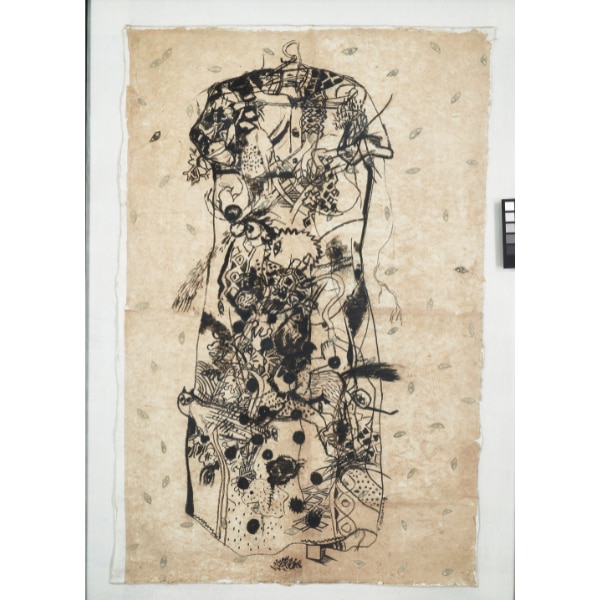

All mages: Courtesy Siddharth Somaiya, Nupur Dalmiya, Rhea Kuruvilla, Saloni Doshi, and Jaiveer Johal

This article first appeared in Bazaar India's January 2026 print edition.

Also read: An insider’s guide to India Art Fair 2026

Also read: India just got its first fashion café in Mumbai—here’s what to expect