How we learned to dress smaller in cities that were built to be grand

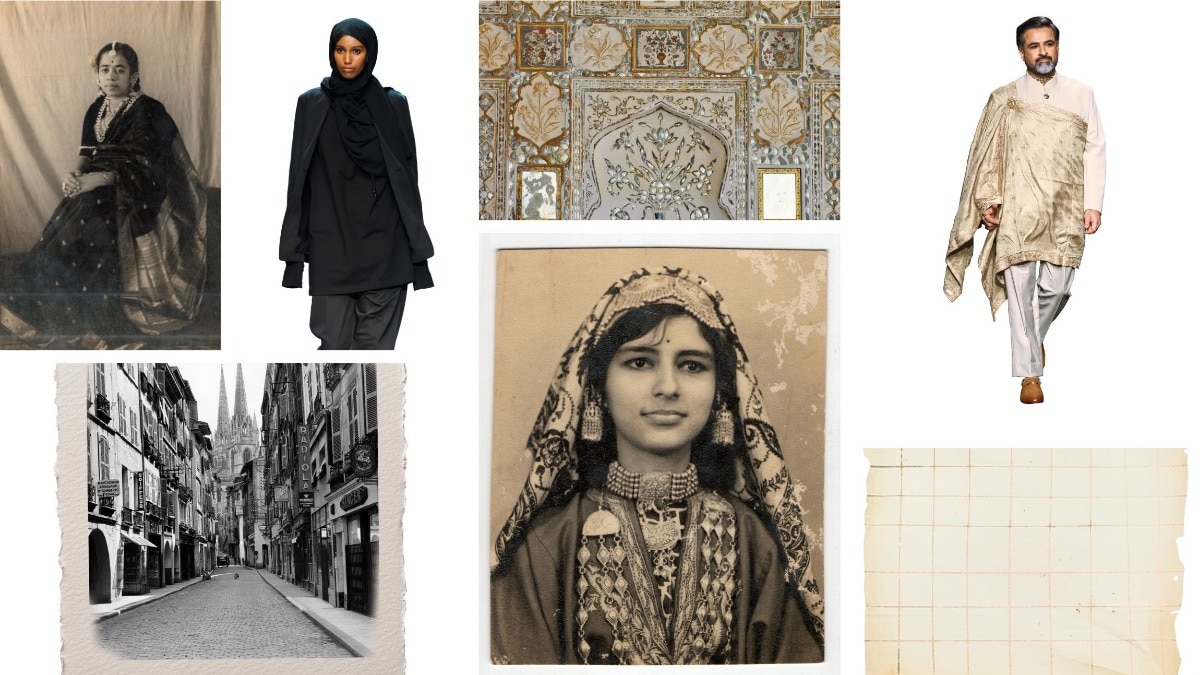

Throughout history, clothes have always filled in the gaps where words couldn’t. Why did we lose the theatrical, performative element of fashion in our daily lives?

How does a city reveal itself? The most global cities of the world do so through their streets, and, by extension, the people on those streets. We observe the cut of an overcoat, how someone styles it with a chequered scarf, the way a street’s sartorial homogeneity breaks when a man decked in gleaming leather, studs and suspenders tiptoes on the cobblestones, wearing graffitied headphones.

A city is the cradle of civilisation, its very zenith. It’s a place where human ingenuity finds its best and worst forms. Paris, some say, is so fashionable. Amsterdam too, but only in the nights, when its sex clubs roar with techno and house music. How about Rome? What should people wear in the imposing, intimidating shadows of a glorious civilisation? How can you beat the Colosseum or the orgiastic glory of the Trevi Fountain?

In India, as history has borne out, people have gone to great lengths to not simply dress for an occasion but to always dress, as we put it now, extra. In the famed Indus Valley Civilisation, beads, bangles, patterned shawls, and styled hair far exceeded survival needs. Even if we don’t go so far and look at early historic India, the Mauryan–Shunga–Kushana period, sculptures show ordinary people layered in jewellery, pleated garments, anklets and belts.

In 2025, we are looking at a different India. Clothes have become stratified. We expect every man from Kurla to colour his hair in at least four different shades of purple and gold and wear skimpy jeans and gold-mirrored wraparound sports sunglasses. Even beyond the heavy classist and casteist connotations of it, the spectacle of a human being dressed in full volume, not minimising himself, gives us the creeps. This is not new or even unique to India, although our deep social divisions do exacerbate it greatly. In The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (1956), the scholar Erving Goffman argues that social life operates like a theatre. People perform roles according to situational scripts, and social breakdown occurs when the wrong costume appears on the wrong body and performance exceeds the role assigned.

It is perhaps for this reason that our cities have become spaces where people will not exceed their sartorial mandate. If they do, they will be immediately policed and constrained to their own spaces. We see the evidence in everyday language. In Mumbai, it’s a common refrain: “I’m sorry, I do not go beyond the sea link.” In Delhi: “Why do we have to go anywhere beyond South Delhi?” It is precisely the social breakdown that Goffman mentions—when people move, their style moves with them, and that unsettles us.

SHADOW OF PERSONAL STYLE

The distinction between a city and a village is crucial to understanding the problem of the dilution of performative style. In rural spaces, or, more specifically, in tribal communities, performative style reigns supreme. To the outsider, it’s all costumes. There is no lateral movement in those spaces, no room for transcending class. The Bison Horn Maria community in central India still wears the horns of the bison as headgear, along with elaborate red beads. The Rabaris of Rajasthan and Kutch still decorate their homes with mirrorwork and wear the Kediyu, a short, flared cotton tunic, usually white, pleated or panelled. The flare and cut make the body visible in motion: functional, unmistakably performative.

The sight of Rabari men walking in tandem, of the Rabari women and their odhnis dense with geometric motifs and bold colours, stands out against the white, barren, unforgiving desert. The corollary is simple: People dare to dress in bold colours and motifs if others around them do so too, because each style decision holds historical import.

Enter personal style: it tramples over precisely the comfort that community dressing, read performative style, offers. Capitalism, its parent, breaks this shelter apart. Capitalism did not erase performative style so much as reroute it, away from shared rituals and into the market. In doing so, weirdly enough, it ultimately creates an army of mundane clothes. The term “white collar,” popularised by Upton Sinclair in his 1930 book White Collar, referred, clearly, to clean jobs, not stained by dirt. White for rich, white for posh.

An army gets created. Homogeneity is achieved. A woman, who inherently feels flamboyant and finds the yoke of a white collar shirt suffocating, has no choice but to wear it—the very antithesis of fashion. A softer variation of the same theme is the dress code at parties. Historically, across Europe, China, Japan, and parts of the Islamic world, sumptuary laws dictated who could wear silk, fur jewels, certain colours, how wide a sleeve could be and how much embroidery was permitted. The modern dress code at parties has, unfortunately, carried the mantle. It’s often vaguely worded, embarrasses people, and sends them scampering for new looks they don’t have just to fit in. If the theme of the party is black chic, it’s an open forum for everyone to judge how un-chic everyone is. All this aligns closely with Max Weber’s idea of rationalisation: efficiency replacing expression.

When the cracks appear, they lay bare the sheer inefficiency of it all, if anything. In September 2025, in the United States, Starbucks workers in three states took legal action against the coffee giant because it changed the dress code without reimbursing employees who had to buy new clothes. Karnataka’s 2022 hijab ban by several colleges showed us how unnecessary it is to force homogeneity when it lacks any historical basis. How can we forget the iconic Calcutta Swimming Club incident from 1987? Ananda Shankar, a cousin of Ravi Shankar, was denied entry because he simply wore a churidar-kurta.

What Shankar said during the incident, as reported by The New York Times then, most pertinently summarises the invisible intersections of it all: “Today, they take exception to the churidar kurta. Next, they will not allow you in because of the colour of your skin.” It is no coincidence that the club allowed only Caucasians until the 1960s.

TRENDING, TRENDING

The problem is rather simple. When a community dresses of its own accord, style blooms. This is not to romanticise community dressing. History shows it can often be rigid, hierarchical, and punitive—but it at least made the rules visible, shared, and collectively negotiated. When a capitalistic hegemonic order imposes a way of life and style, it is all about a uniform. This brings us to the last enemy of performative style: trends. Although the word “trend” originally comes from Old English trendan, meaning to turn or revolve, the first serious theorisation comes from Georg Simmel in his 1904 essay Fashion. His theory was simple. Fashion works through a tension between imitation and distinction: elites adopt something new, masses imitate it, elites abandon it, and the cycle repeats. This is the birth of the modern trend cycle and the death of performative style.

All these barriers stand between us and a style that knows no bounds—the slow march of capitalism, the manipulativeness of personal style, and the toxic loop of trends. And how refreshing an exercise that is, because to collapse these barriers is to also take the first step towards not thinking like a petulant, hormonal teenager who won’t budge beyond his irrational boundaries. Performative style persists because bodies continue to exceed the roles designed for them. Let the roof come down, let the theatre that Goffman refers to break down. Let us take space, not minimise ourselves and, as Dylan Thomas famously wrote, not go gentle into that good night but rage against the dying of the light.

All images: Courtesy Getty Images; Shutterstock; and Tasva

Artwork by Trushieta Naringrekar

This article first appeared in the January 2026 issue of Harper's Bazaar India

Also Read: Can’t commit to one vibe? These contrast fabric garments don’t ask you to

Also Read: Valentino Garavani, the man who showed the world the power of red