The fashion that doesn’t seek attention

The fashion industry grinds us down, pushes us against the wall, and leaves us tossed about: wide-eyed, mouths agape. We rant about how it manipulates us into believing that a better life is always just weeks away. But what does a way out look like?

In Bastar, the Naxal epicentre of India in Chhattisgarh, you start your day with a serving of chapda, chutney made with red ants. Men stare at you blankly, and you return the gaze with suspicion.

Are they sizing you up? Might you be a conspirator of the state? With every turn of your rickety Bolero, snaking its way through the Dandakaranya forest, the air grows heavier, acquiring a familiar weight. Along the way, hammer and sickle signs greet you, plastered across tapered tombstones. You are on edge, but no gun is cocked at your head. As the sun beats harder, the driver has a surprise: his wife has prepared the famous black chicken of central India, Kali Masi, for lunch. Won’t you come?

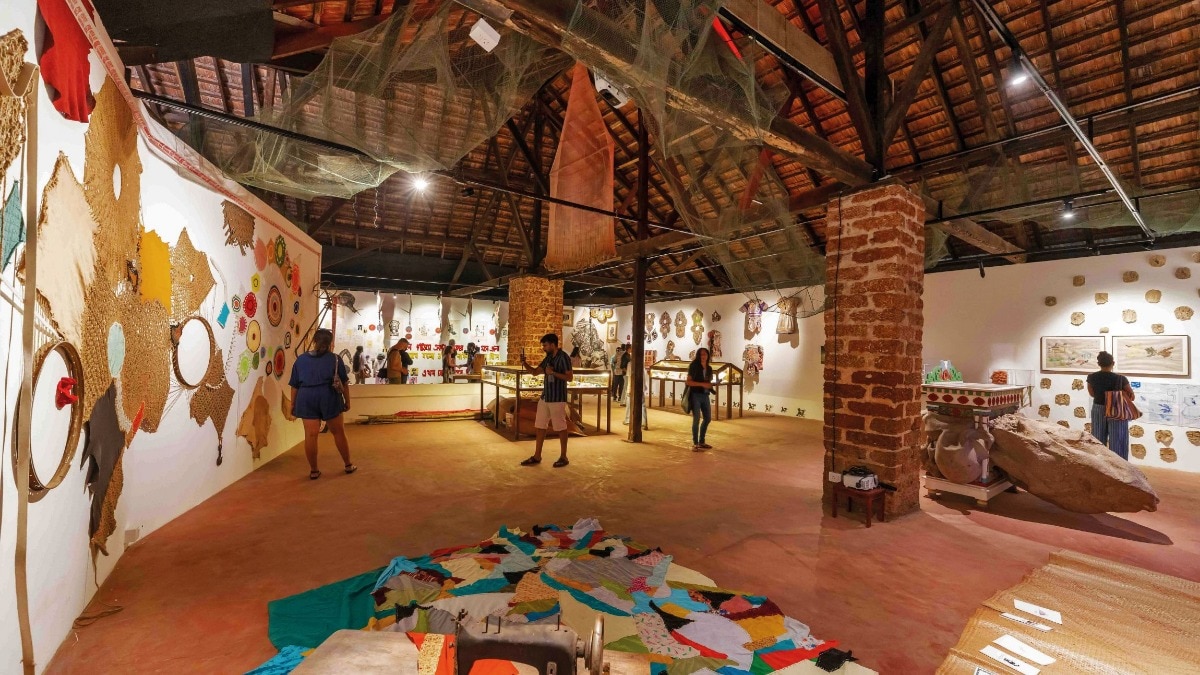

When you step into their thatched-roof cottage, the real surprise is the handloom in the courtyard. Over the past six years, she has been weaving the Jambudvipa, the Jain cosmological map with its concentric continents and oceans, Mount Meru at the centre, and the surrounding regions where humans and celestial beings dwell. She has employed the soof embroidery, a counted-thread technique of western India. Each river—Ganga, Rohita, Harit—is rendered stitch by stitch without a traced outline. She is Jain, so this is simply a prayer for her. It is not for sale. No designer will be allowed to use it as a backdrop for their fashion show. You would like to ask her questions, perhaps praise her. If this isn’t the intersection of fashion and art, what is? But she is not looking for your validation, and it is lunchtime.

This was in October 2020, when I visited Chhattisgarh for a National Geographic assignment. The brief was to cover the Ramayana trail, a significant portion of which wound across Bastar. That overwhelming tapestry of the Jambudvipa was certainly not on my bingo card. But that was the first time I realised how narrow my understanding of fashion had been. Shorn of art and spirituality, fashion, to me, meant a fragile dress with Velcroed frills priced at a ridiculous markup. It meant an echo chamber swamped with incoherent Pinterest boards and advertisers poring over Excel sheets.

As I stood before the sprawling cross-weave of human ingenuity,I wondered how easily we had all let the world drain fashion of meaning, to some degree. It lived in the red alleyways of Bastar, just as vibrantly as it did in the mirror-work ghagras of Kutch, or the loom houses of Kanchipuram, where the clatter of shuttles rhymed with temple bells. But it was also in the sea of men and women, cloaked in white coffin cloth, when I circumambulated the Kaaba in Mecca for Hajj a decade ago.

Five years later, as I renegotiate my relationship with fashion, it is through the prism of this meaning. In the tesseract-coded illusion of our cities, it is easy to be jaded, to believe that fashion and stories do not matter. I would very much like not to reach that stage.

For me, the question of fashion has always carried a different weight. I graduated in mechanical engineering, also known as the most cishet qualification. That was the only time I flirted, very briefly, with quitting everything to sell apricot jam in Shimla, because there was nothing redeeming about gears and grease. In our bi-weekly workshops, I operated lathes, chamfered high-speed stainless-steel tools, learnt carpentry, and hammered molten metal into sheets. All the while, in my college bag, backdated copies of i-D picked up from scrap shops lay pressed between dreary tomes on thermal engineering and fluid mechanics.

It was my first brush with a life of contrast. Perhaps this is the only way to survive the horrors hidden like carpenter ants in the woodwork of an ordinary life. Cuts on my palms from an overzealous lathe? Instead of whining, I made peace with fashion spreads. When we refer to fashion as an escape from mundanity, this is what it looks like: a rose garden blooming amidst the clanking of machines.

These annoying machines that threaten to disrupt the peace of fashion’s rose garden, its very core, can take different forms depending on your job profile. They might arrive in the shape of devious Excel sheets, or the grid-shaped nightmare of a Zoom call. They might be a gaping void formed by the numbers in the accounts book that do not match because a critical merchandise batch failed to sell. Or they might take the shape of a marketing misfire. In all those cases, it is easy to forget that our garden is right there; we just have to ask all those machines to shut up.

When we are consumed by the perks and privileges of our lofty positions, it becomes easy to forget the impermanence of fame. That is the loudest machine, if you ask me. We lull ourselves into believing that we are really that special, that we are bigger than fashion. We become capable of engineering a riot because we did not get the front row or were overlooked for that stunning beauty-care package from some luxury brand, complete with ribbons and letters. So, can we achieve the equanimity of the master artist of Bastar? That is perhaps too much to expect from our weary, painfully urban hearts. But it is possible to take the first step.

We are not the prisoners in Plato’s allegorical cave, deluding ourselves into believing that no world exists outside its bleak shadows. We do not need to wait for a nervous breakdown in order to switch careers, unfollow all fashion pages, and recoil from the spectacle of it all. Ask anyone with a creative bone in them and they will tell you that their biggest fear is irrelevance: the twenty thousand vacant seats in the amphitheatre of their minds, single-page views for articles they thought would bring them fame, Instagram likes so low they are forced to turn off the count.

It is this fear of irrelevance, and ageing, its conjoined twin, that will not let us pause. Yet we all know too well that fashion, like the Jambudvipa stitched in a courtyard in Bastar, is at its most powerful when it exists just a few seconds away from fear. Or, as the character of Subrata Mazumdar says to his rebellious but inconsolable wife at the end of Satyajit Ray’s Mahanagar (1963), after she quits her job: “I could never have done what you did. I would not have had the courage. Earning our daily bread has made us cowards. But you were not a coward. Is that a small achievement?”

Lead image illustration by Shreya Arora

This article first appeared in the October 2025 print edition of Harper's Bazaar India.

Also read: Feel the grounding energy with these botanical-inspired designs