This is what fashion looks like when you take your time

Raw Mango's Sanjay Garg continues to question place, perspectives, and purpose in his pursuit of defining a new aesthetic vocabulary.

To comprehend Sanjay Garg or his brand Raw Mango, it’s imperative to dive deep into the man’s school of storytelling and his true intentions, shaping the “whys” more than the “whats”. It takes me back to a session I had attended on Geoffrey Bawa’s garden ‘Lunuganga’, in 2023, where Garg spoke at length about reinforcing material memories with changed conventions to create the visual identity of today and the future. To contextualise the same ideology in his journey as a designer, Garg reflects, “Fashion can be a victim of tokenism. From plus-sized model to deep-skinned one—the industry works on one formula or the other, but we started way before it was ‘cool’.” For the initial five years, he didn’t have fashion photographers onboard, rather worked with travel photographers from news background, as his inclination towards documentary-like campaigns goes long back before the onset of the social-media aesthetic.

The designer reminisces about the casting for his 2017 collection campaign, Cloud People, that featured models from the Northeast. While the collection revisited chikankari as scalloped clouds of angels on Bengal mul, zardosi, and brocade, the campaign—shot by Ashish Shah—caught everyone’s attention. “In a way, we started the movement of casting real people in our campaigns eight to nine years ago. Now, everyone has picked it up, and once again it has become a recipe.” At that time, Garg refrained from the “trend” of featuring international models, especially from Sri Lanka, as he wanted the “real” people of India to be a part of his story. “Those kinds of sentiment, those kinds of provocation are crucial. The country is known for its rich storytelling, right?” he asks rhetorically. “We have diverse oral histories. There are several languages and dialects. If we don’t tell these stories, who else will? So, when I saw outdoor campaigns, I thought we could do much better than making the models stand in front of the palaces. There came a provocation to create a unique visual identity for Raw Mango,” Garg tells me as I sit next to him at the Raw Mango Headquarters in Gurugram. There’s an abstract artwork by Jeram Patel on the wall behind us, coexisting with a couple of chairs in the front picked from Chor Bazaar in Delhi. Terracotta antiques are lined up in glass boxes next to us, a sculpture from Cambodia on a stone table from Rajasthan, two gigantic busts hang at the reception desk, along with a framed Rashmi Varma embroidered map of Delhi, 1924, at the front—this is the collective essence of India to Garg.

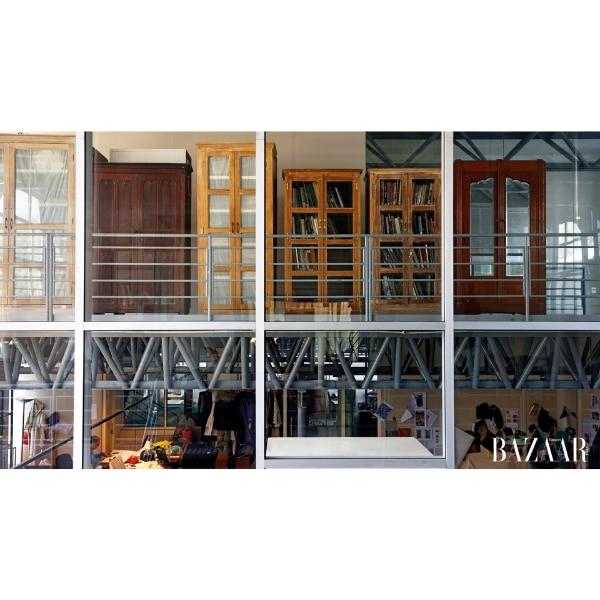

There’s more; contrasting icons of rituals, like Catholic statues, find space alongside Jaffna sculptures and 19th-century metal chairs in different shapes surround a huge table in the conference room. I am told the chairs are uncomfortable and could be Garg’s way of keeping the meetings short. The designer laughs at the jest thrown around by a team member. Across the conference room and upstairs, there is a library of his archival materials. Gigantic clay and brass vessels line the ground floor—the space is nothing short of a maze-like sanctuary, one that serves as a constant reminder to revive lost narratives.

As an aesthete-maker, the designer has a mature reaction towards being copied or the alleged “sameness” in aesthetic vocabulary in the fashion industry. “Honestly, earlier it used to bother me a lot. I definitely had sleepless nights. But now, for the last five to six years, I don’t think about it much. It’s not an easy path, because everyone keeps asking, ‘What is new?’ You have to dig deeper every time to come up with a story, but you are on the edge. Everyone has high expectations, and you are only fighting with your last campaign in a way. While it’s difficult, I think it’s also interesting and challenging at the same time.” He happily puts it as a breath of fresh air. And whether or not he has contributed to it, Garg is neither looking for acceptance nor does he feel threatened, “not anymore...,” in his words.

Ideologies move the needle for him. From limited participations at fashion weeks, preferring to be called a “textile designer” over a fashion designer, to getting bored with media asking “what’s next”—the list makes one sit up and brood. “If I don’t have anything new to show, I don’t deserve to be there. I don’t want to take someone’s space. I will be showcasing next year since I have built something new. There are other things, like campaigns, diverse artistic interests, and collaborations, when I don’t have anything new to present at fashion weeks.” Fashion shows are not the only medium to build a brand, in Garg’s opinion. “For instance, while we have brands like Gucci, Chanel, Dior, we also have The Row—they don’t allow phones at their shows. Then, there’s Hermès—they don’t have to vie for red carpet moments. This brings us to the concept of parallel movement in fashion, and it is where Raw Mango comes into the picture,” he makes a point. There is an entire system in place, and the audience grabs and grasps information differently. “As a brand, I am buying space in your head in my unique ways, not necessarily a fashion show every time.” Talking about his ways, Garg is known for his intimate baithaks and parties where style takes precedence over fashion, or his long-time collaboration with India Art Fair, from where his famous rose-petal shower has been replicated in many ways.

Culture and community have to be factored into the textile designer’s road to success, albeit not a linear one. From humble roots in Mubarikpur, Rajasthan, dismissed for his bright colours by renowned multidesigner brands, to finding his community at Dilli Haat and Dastakar Bazaar, Garg has come a long way in creating an identity and finding his fraternity in the industry. Today, artist Dayanita Singh, politicians Mohua Maitra and Shashi Tharoor, film-maker Kiran Rao, and craft activist Laila Tyabji are among his brand loyalists. It has taken him so much more than fashion shows to build these associations over the years.

A deeper understanding of community extends from brand patrons to Garg’s artisans. Over the past 16 years, he has extensively collaborated with clusters across the country, like Chanderi and Mashru, and worked with karigars from Rajasthan and West Bengal, to Varanasi. His vision for them stems from cultural and ethical contexts rather than marketing fluff. “Let’s take a hypothetical situation,” he pauses before continuing, “I am showcasing an indigo collection for which I have worked with an artisan who learnt to dye it from his ancestors. Later, if I am supposed to come up with something ‘new’ and choose a different trend or technique, the same artisan will cease to be in ‘trend’ and will not have a job.” This is the reason why working in a slow and sustainable model is essential for Garg. “For instance, we have been working with Chanderi for the last 15 years and continue to do so with every team. Whenever we add a new textile, we ask: Do we have enough business for the artisans to sustain themselves? The artisans don’t need our sympathy; all they need is ethical business and fair wages,” he adds.

He brings up the brand Anokhi as a reference point. “Their unparalleled commitment to the block printing technique over the last three decades has been a game-changer that no NGO could have achieved on their own. They catapulted several brands in the process, and now, we have block prints everywhere.” Such artisanal interventions can’t last over six months; these have to be long-term goals. “You are creating a sustainable ecosystem. The craftsmen don’t care about your photo-op tokenism. Some of them can afford cars, air-conditioners at home, their kids can go to schools, and some get to study at NID or NIFT. This is what matters,” Garg explains.

While visual identity sits at the front and centre of Raw Mango, it never comes at the cost of design interventions and innovation. Garg is a firm believer in functional creativity; it is what drives the course of visual creativity. Form and function go hand in hand. “We have lost so many textiles and techniques for a reason. We can’t blame the young generation if they don’t want to wear ‘tradition’. As a designer, it is my responsibility to understand the gap and bridge it.” The designer has strategically leaned into innovation to serve tradition—from design-forward blouses, embellished petticoats back in 2013, to mixing brocade with Lycra and experimenting with welded sculptural techniques for his collection, Children of the Night, in 2024. While at the core, he is a traditionalist, Garg predicts that the future of handloom is in a design-centric approach. “We need to constantly push the envelope—change the pattern, fall, surface textures. Traditions have to be reimagined, and we are doing it with different kinds of material and yarn.” Questions about the relatability of a final product can be answered with practical solutions.

The designer turns to surrealism for his upcoming festive collection, Once Upon a River, filmed at a heritage palace in Santrampur, Gujarat. Layers of surface ornamentations are woven in brocade. Weaving (bunai) and handwork (kadhai), which are traditionally imagined as independent crafts, will come together. “We created a huge paper-mâché horse and bird—the scale of it is very interesting. We have tried to create a land of dreams,” Garg shares with excitement. Additionally, as part of a major Indo-French exhibition in December in France, curated by Christian Louboutin and Mayank Kaul, Garg will showcase a pivotal point of sari drapes.

All images: Tongpangnuba Longchari

This article first appeared in Bazaar India's September-October 2025 print edition.

Also read: Godet: The vintage tailoring detail that’s bringing back flare with flair

Also read: Rummy, romance, or rooftop ragers—a Diwali dressing playbook for every plan