The 19th-century trademark law that gave us the hottest labels you’ve never heard of

An exhibition at the Museum of Art & Photography in Bengaluru is a portal into an entire visual language born out of necessity—the art of the textile trademark in Indo-British textile trade.

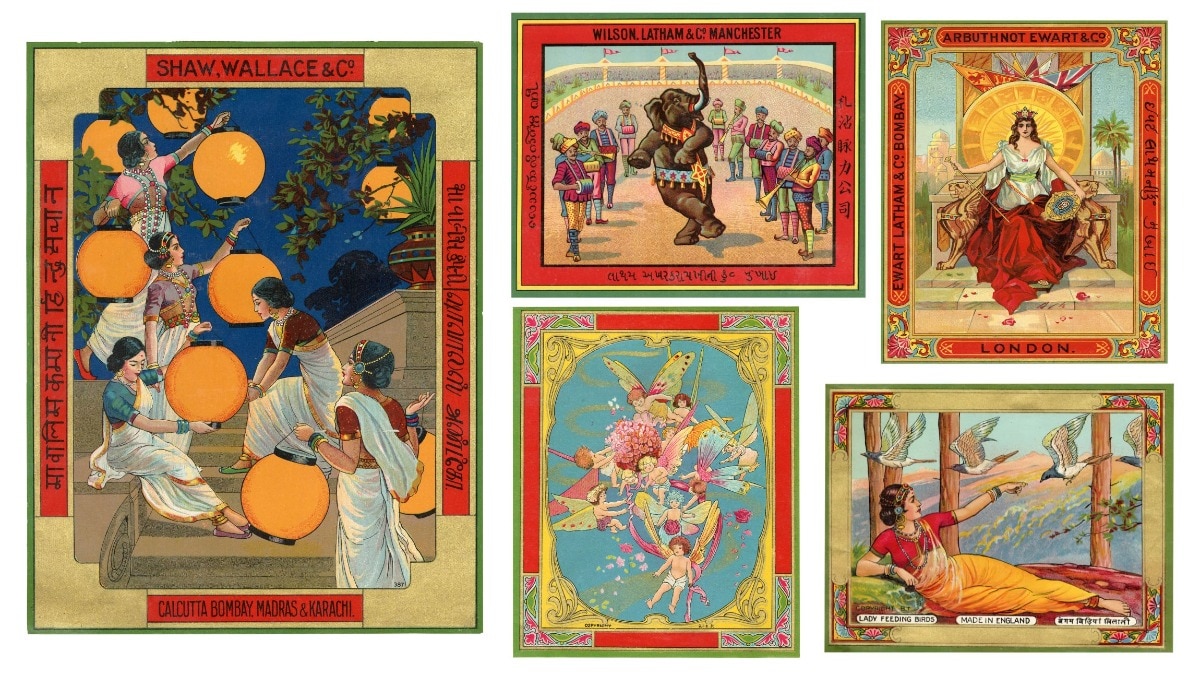

I was in Bengaluru, skimming through the air-conditioned quiet of the gift shop at the Museum of Art & Photography (MAP), thinking vaguely about lunch. It was a pit stop in my slapdash weekend visit to the city, and I wanted to stop by to take a quick look at Ticket Tike Chaap, an exhibition showcasing textile trademark labels from the 19th century. Fifteen minutes in and out, I told myself. Until I climbed up to the third floor and saw it: women in saris, hanging up illuminated orbs on what looked like the lovechild of a postage stamp, a tarot card, and a hand-painted movie poster. Above it? “Shaw Wallace & Co.” Below it, “Calcutta Bombay Madras & Karachi.” I think I gasped.

Almost immediately, the exhibit became more than something to tick off my Bengaluru weekend checklist. It wasn’t about design for design’s sake, it was about branding before branding had a name. A whole genre of textile trademarks that loomed large in the 19th and early 20th centuries, born purely as a result of some good ol’ fashioned colonial red tape.

Here’s what happened: British mills that wanted to sell cloth in India suddenly found themselves within the purview of trademark laws. They could no longer stick their names on the bolts of cloth and call it a day. Instead, they had to create a symbol—something unmistakable, unforgettable, and crucially, unlike any of the others.

Enter the ticket, the tika, the chaap, as they came to be known. More than mere identifiers, these tickets were the ingenious solution to the very pressing problem of trademarking goods in a market with little literacy and rampant counterfeiting.

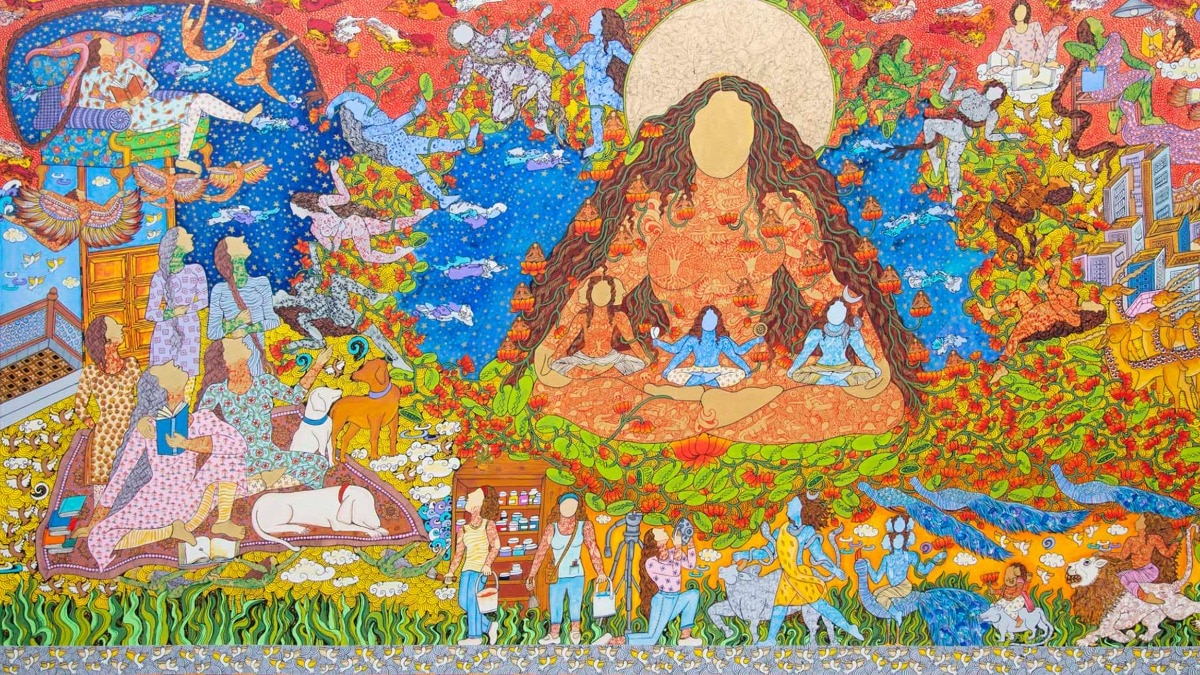

Factories in Manchester (and later, Indian mills) began to come up with imagery that would feel instantly familiar to Indian buyers: gods, kings, peacocks, temple elephants, even the odd portrait of Queen Victoria looking slightly miffed. Employing the then-novel technology of chromolithography, the art on these labels drew from everywhere—Mughal miniatures, local devotional posters, and the occasionally plagiarised royal manuscripts and religious iconography. The result was a visual genre entirely its own, each label revelling in itself—the art forced to be at the intersection of commerce and culture.

To walk through the exhibit is to witness a riot of contrasts between East and West. On one label, the goddess Saraswati is perched serenely atop a lotus beneath the stamped seal of a British cotton company. On another, three White women look coy in their swimsuits at a bathhouse.

Some labels are lush with Indo-Islamic motifs—pomegranates, archways, flowers, and birds—clear derivatives of historical, hand-painted manuscripts. Others feel like precursors to Bollywood posters painted in an era before digital printing became the norm: loud, joyful, and impossible to ignore. And people noticed even then—these tickets weren’t tossed aside. In some homes, they were framed. In others, they became devotional objects, stuck on walls next to the gods who were there before. With branding like that, who needed an Instagram reach?

What’s evident is that the curators, Nathaniel Gaskell and Shrey Maurya, and designer Shruti Singh at the MAP Academy, have presented the labels as more than just nostalgia. The tickets were pulled from MAP’s archive and arranged with the reverence typically reserved for rare books or fine art.

And they are fine art, in a way. The kind born of necessity, adapted with cunning, and executed with flair.

Standing there, surrounded by gods and gears, elephants and Empire, I couldn’t help thinking about how we spend so much time trying to figure out what “Indian design” means. But it’s been right here all along—half sacred, half slick, full of complexities, and meant to be seen, touched and remembered.

So no, I didn’t make it to lunch. I frolicked instead in a room full of tickets of lore and lions, struck by the brilliant audacity of the ordinary. By the labels that outlived the textiles.

And what could be more fashion than that?

Lead image: Philippe Calia and MAP Bangalore

Also read: How travel became performance—and we all played along