How travel became performance—and we all played along

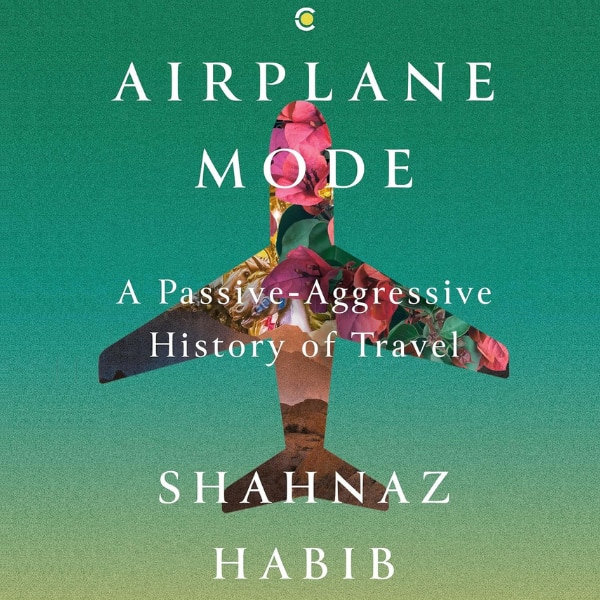

Bazaar India chats with Shahnaz Habib, the author of “Airplane Mode,” on the myths, language, and framework of travel—and all the questions we’re not asking.

It is perhaps the great con of our times—for years now, travel has been sold to us as this horizon-expanding, mind-broadening, self-improvement experience. It’s really quite remarkable how the modern travel industry has taken the very human instinct to move—and chalked it up to a slick, well-marketed, Instagram-filtered product. To travel is to live, to grow, to “discover”, they say. But, a closer look reveals that it’s about something far more complex—and at times, deeply problematic.

Shahnaz Habib, author, translator, and tourist, unpacks the notions of modern travel in her book, Airplane Mode: A Passive-Aggressive History of Travel (published in India by Westland), where she holds up the mirror to the very beloved activity and examines its many complexities—who gets to travel, for what reasons and under whose authority, and how we got here. She doesn't always have the answers but she's unafraid to ask the uncomfortable questions—in a way that's probing, witty, and scarily self-aware, she nudges us to reconsider what we take for granted when we pack our bags and take off.

In conversation with Bazaar India, it is soon apparent that Habib is both in love with travel and deeply sceptical of it. “That love-hate relationship is very much at the heart of this book. It's probably the reason I wrote this book. Because I bought into all these myths about travel being this horizon-expanding business and everyone should do it for cultural enrichment. And I still think, to a certain extent, it is all true. But the way tourism has been sold to us as this must-do activity is false,” she says.“It is very much the way capitalism and individualism train us to think—that we are special. ‘I am going to go on this experience of self-fulfilment and self-discovery, and this experience is going to be different from everybody else's experience.’"

And she’s right—in fact, not having seen the world is often perceived as unsophisticated and ultimately unfulfilled. The influencer-industrial complex has turned travel into a Pinterest-worthy checklist, where experiences are curated for an audience before they are even lived. And travel, once an act of movement, has become increasingly about the performance of movement.

Habib explains, “You're already thinking about what you're going to do when you get there. And it's not necessarily what you may like to do, but what you see people around you doing. When the iPhone introduced the selfie option, I think it marked a huge change in the travel industry because it shaped the way people recorded themselves travelling. Of course, we’ve always taken photos when we travel, and travel photographs are a genre by themselves. But the fact that by taking a selfie, you can just record yourself very quickly, very cheaply, without any assistance—that marked a big shift in the way we made travel a performative activity. So, for instance, there was one year when the New York Times reported that people actually had to step over dead bodies in order to get to the top of Mount Everest and take a selfie. Imagine a delicate ecosystem like a mountain peak and what this kind of consumerist travel is doing to that delicate ecosystem.”

And beyond the selfies and the filters lies a more uncomfortable truth—all travellers are not created equal. There’s the matter of access itself. Who gets to travel? Who gets to tell travel stories? As it so happened, the face of travel, historically and overwhelmingly, has been White, male, and able to cross borders with ease. “When you look at the travel book section of a bookstore, so many of the great narratives of travel are written by White men. Until very recently, it was only the young White man who was able to just leave home and go and live wherever he wanted, without worrying about money, safety, or whether he had the right documents,” Habib says. But for everyone else—women, people of colour, those carrying third-world passports—travel is as much about movement as it is a confrontation with bureaucracy and bias. She continues, “When I talk about passportism, for instance, when I talk about this book to White people, it's often their first glimmer of understanding that there is this whole discrimination built into travel. That when they reach an airport, they can just walk through the arrival lines, while all the Brown people with third-world passports go to those long immigration lines and wait for like two-three hours before they can get out of the airport.”

The language of modern travel, in fact, thrives in this arrogance and yet, is so far behind acknowledging it at all. The travel industry has managed to laugh all the way to the bank while feeding us the “traveller, not a tourist” trope and having co-opted words like “discovery” and “exploration,” oblivious to and regardless of the baggage they carry. Habib points out, “Travel narratives of the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries were built on this idea of discovery where the colonial governments that were sponsoring expeditions were doing this very deliberately. They were not sponsoring travel; they were sponsoring colonial exploration. So, the word ‘discovery’, as used by these early modern travel writers and explorers, was used very deliberately to fashion a colonial narrative about discovering a place for England or Spain or Portugal. In Portuguese, the word for exploring and exploiting is actually the same word. I think modern tourists have unconsciously just inherited this framework of exploring in ‘discovery.’”

The medieval Arab world on the other hand, Habib notes, had a far more humble and poetic way of travelling: the framework of wonder. “[It would be] going to a place and feeling a sense of wonder at how different this place is from the place where they came from. And with the framework of wonder, it means you're not setting yourself up as this neutral, objective, only important point of view, which is exploring and discovering these other places. You're saying, ‘I’m weird. This place that I'm going to is weird. Look at the strangeness between us.’ And that framework of wonder was kind of built into the way the medieval Arabic Rihla (travel narratives) were written. So many of them are known as the ‘Book of Wonders’ because that was the idea.”

Perhaps it is this humility, a shift from discovery to wonder, that might just be the way to move through a world that is rife with modern complications. But the wonder framework is not without its limitations—medieval Arab travellers were travelling, wondering, when the Islamic empire was at its peak, so they likely had the same confidence that American tourists do today. They were not, for instance, familiar with what it felt to be othered, they were not travelling through a climate emergency. Habib suggests a new way to think about travel instead: solidarity.

“So much of modern travel is premised on customer service,” she says. “Instead of thinking of the locals in the places we are travelling to owing us customer service, what if we thought of ourselves as being in solidarity with them in living in a really hurting world? It's something I'm trying out.” She acknowledges that even this framework is fraught. Solidarity can easily veer into patronising saviorism, into yet another kind of performance. But the point is to keep questioning how we can do better.

Habib recommends dropping the main character narrative. "When I call myself a tourist, I want to shake that idea out of myself. I also want to have a very dramatic self-discovery, an epiphenic travel experience. And I hate how it just takes up so much space in my head. By calling myself a tourist and embracing that the things I do are touristy, I want to put some distance between myself and this idea that somehow travel is this individualistic, self-fulfilment experience because it is not. It is such a collective experience. It's a trillion-dollar industry. We're travelling with millions of people. Even if you take just tourists, that is a significant number. But then when you think about all the people who are also travelling as migrants, as refugees, people who are travelling for work, people who are travelling because they're fleeing, this is one of the biggest collective experiences of the 21st century—going somewhere.”

Maybe the most radical thing we can do, then, is to travel better—not as consumers collecting experiences for our feeds, or protagonists "discovering", but more mindfully, as witnesses to a shared world. One that is uneven, strange, and astonishing all at once. Perhaps we can move not with entitlement, but with empathy. Travel, at its most honest, can be about remembering we are not the only ones. And that's not a loss as much as it is the beginning of wonder.

Lead image: Pexels

Also read: How these organisations are rescuing India’s traditional arts from obliteration

Also read: The micro-retirement revolution: Work less, live more, thrive now