The power of a fiery red ruby, the serene depths of an emerald, and the sparkle of a sapphire seem to surround us with an explosion of colour in jewellery. But did we always live immersed in mineral colour? If not, when did this vibrant shift begin—and more importantly, why?

To answer that, we must journey back to the late 1800s, when diamonds were first discovered in South Africa.

For over 3,000 years, India was the only source of diamonds, attracting merchants and explorers from faraway lands. That monopoly was broken around 1725 when diamonds were found in Brazil. Yet nothing prepared the world for the South African diamond rush in the late 19th century. The sheer scale of production led to the founding of De Beers in 1888 and the Central Selling Organisation (CSO by De Beers) in 1890.

After oversupplying—and seeing prices tumble—De Beers quickly recognised the importance of controlled distribution. They created a network of ‘site‑holders’ tasked with purchasing rough diamonds, cutting them, and bringing them to market. To create and preserve diamond value for the sustainability of the pipeline from mine to market, De Beers initiated a series of consumer‑facing marketing campaigns ushering in the ‘diamond decades’.

To create, a painter needs pigments. Since De Beers’s establishment, the company has dominated the colour palette in jewellery. When the GIA introduced the four C’s—cut, colour, clarity, and carat—in 1953, they offered the industry a clear value framework. Yet there’s a fifth C everyone overlooks: Consistent supply. Reliable mining and manufacturing meant jewellery makers, designers, retailers could invest in acquiring and marketing diamond jewellery—no point promoting a stone that can’t be found when a client walks in.

In contrast, coloured gemstones were rare, sporadic, and typically relegated to accents or boutique pieces by specialist designers.

That changed in 2007, when Gemfields challenged the status quo. But the stage was set even earlier. Today, more than 80 per cent of coloured gems in global trade are African. After World War II, as African nations gained independence from colonial rule, they began exploring their mineral deposits for nation-building. But unlike diamonds (mainly carbon), coloured gemstones form under rare geological conditions, chemical reactions between different rock types and trace elements. Zambian emeralds, as an example, were formed around 550 million years ago. The sporadic and limited scale of gem deposits makes large-scale institutional investment unlikely.

Enter Gemfields: Their acquisition of Zambia’s Kagem emerald mine transformed the game. Emeralds were discovered in Zambia in the sixties, but despite illegal digging and formal mining, the global impact was limited.

Gioco di Forme e Colori watch featuring tanzanite, red tourmaline (rubellite), tsavorite, aquamarine, tourmaline, amethyst, malachite, and sodalite gems, Bvlgari

Emulating De Beers’ playbook, Gemfields invested heavily in one of the world’s richest emerald deposits, building a mining operation of unmatched calibre. In 2011, they established Montepuez Ruby Mining in Mozambique.

Both mines are the main source for emeralds and rubies in the world today, representing over USD 200 million in investment by Gemfields since inception and have generated a combined total of over USD 2 billion in auction revenues.

Alongside this infrastructure, Gemfields established a grading system for rough emeralds and rubies—and introduced a transparent auction system. Sean Gilbertson, Gemfields’ CEO, explains: “Before Gemfields, auctions of coloured gemstones were often haphazard and irregular, with gems of variable quality and size bundled up together. Buyers had to spend months and even years building up sets of gems to make jewellery suites. Gemfields’ proprietary grading system and auction process introduces consistency and transparency to a previously chaotic system, as rough gemstones are sorted and graded by colour, size, and clarity. This increasingly reliable supply has enabled jewellery brands to incorporate coloured gemstones into upcoming collections with confidence, transforming the availability of coloured gems for consumers.”

Ring featuring a Tanzanian spinel, Gübelin

This infusion of structure—and savvy consumer outreach—spurred demand for coloured stones across the industry, attracting players in both mining and manufacturing of gems.

Tarang Arora, creative director & CEO of Amrapali Jewels, confirms the shift: “In the last 10 years, there’s been a clear change in what people are looking for when it comes to jewellery. Colour has become a big part of the conversation. Instead of just sticking to classic gold, diamonds, or all-metal looks, customers—especially younger ones—are now drawn to pieces with colour. Whether it’s gemstones, enamel work, or mixed materials, buyers are looking for something more fun, personal, and expressive. Social media and global trends have played a part in this shift. People want jewellery that stands out, tells a story, or says something about who they are—and colour is a great way to do that. It’s no longer just about what looks expensive; it’s about what feels meaningful or different.”

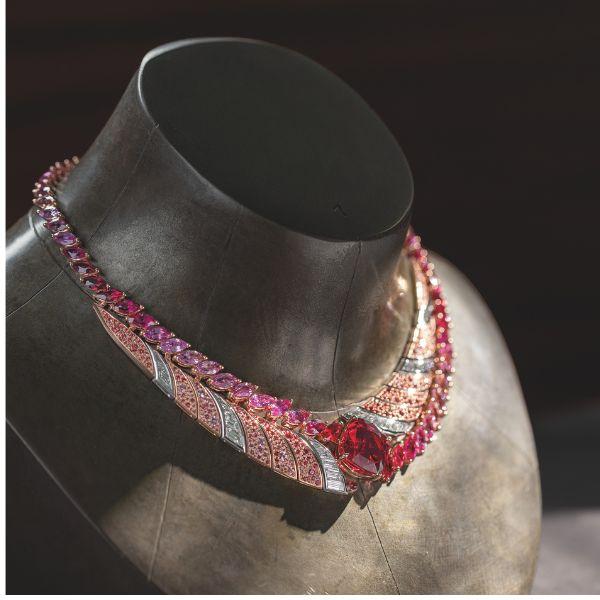

Necklace featuring rubies and spinels, Gübelin

Today’s gem palette has transcended the ruby-emerald-sapphire triumvirate. Spinels, Paraíba tourmaline, tsavorite and mandarin garnets, rubellite, aquamarine, morganite, kunzite, even tanzanite are finding their moment.

And it’s not just fine jewellery—coloured gems are reshaping watches and bridal lines. “About 30 per cent of bridal jewellery today features colour, compared to less than 10 per cent two decades ago,” says Arora. “Retailers also favour gems for higher margins than diamonds. Social media, global fashion, and storytelling in jewellery have all played a part. Colour isn’t just a trend anymore it’s a major shift in taste and buying behaviour.”

Colours of Love Eggsistence rose gold rainbow gemstone Watch, Fabergé; Notte Stellata Diva watch featuring blue sapphires and yellow diamonds, Bvlgari

One final catalyst: Confusion over lab-grown diamonds. As synthetic diamonds flood the market, consumers are turning to top-grade, untreated rubies, emeralds and sapphires—bracing themselves with something authentic and naturally rare. As we look ahead, colour is no longer the exception—it’s becoming the rule. This golden age of gemstones is not only redefining aesthetic preferences but also reshaping how we connect with the jewels we wear. Each coloured stone tells a story of time, place, and provenance. And in a world increasingly drawn to authenticity, individuality, and emotion, that story matters. From rough to radiant, colour is no longer a supporting act. It’s the headliner.

Cufflinks featuring multi-coloured gems, Fabergé

Lead image: Rough emeralds at Gemfields’ Kagem mine in Zambia

All images: Courtesy Gemfields, Bvlgari, Gubelin, and Faberge

This article originally appeared in Harper's Bazaar' India's June-July print edition.

Also read: From beach to the street: Why makeshift sarongs are everywhere

Also read: The Basque waist has fashion in a corseted chokehold