Four Northeast labels that are transforming inherited techniques into contemporary expression

We spotlight four labels from the Northeast that are transforming inherited techniques into contemporary expression.

Four Northeast labels are rewriting what craftsmanship from the region can look like—moving beyond nostalgia and into a sharper, contemporary vocabulary. Instead of treating inherited techniques as artefacts, these designers are retooling them through modern silhouettes, innovative materials, and a design language that feels unmistakably current. The result is a new wave of creativity that is neither bound by tradition nor distanced from it, but fueled by it—proving that the Northeast’s craft legacies aren’t just being preserved, they’re being reimagined for the world.

HANNAH KHIANGTE

We first heard Hannah Khiangte’s name the way many now do—via a viral post of Kareena Kapoor Khan describing one of her ensembles. A sharply cut silhouette in a weave that carried its own quiet authority. It made people ask the right questions: who designed this? And why haven’t we been paying attention sooner?

Hailing from Lunglei in Mizoram, Khiangte has emerged as a designer whose work is rooted in heritage yet fully alive in the contemporary. She does not see the fabrics of her homeland—the iconic puan weaves—as artefacts to be preserved. Instead, she treats them as living narratives, ready for reinterpretation. As she puts it, “It’s never been about simply juxtaposing the old and the new but letting them speak to each other.”

Khiangte watched her mother and grandmother wrap themselves in the richly patterned puan. “In Mizoram, fabric is more than something we wear, it’s how we celebrate, mourn, and remember,” she tells me, attuned to how textiles embody memory, material, and meaning.

The puan finds new expression in Khiangte’s hands. Its linear weaves and bold borders are reimagined through tailored forms—structured jackets, fluid skirts, and sculpted dresses—that preserve the rhythm and weight of the original textile while allowing it to speak a modern design language.

However, she does not attempt to modernise the puan—she listens to it. Her design process begins far from the sketchpad. Khiangte spends time with women weavers who still work on traditional loin looms, listening to their stories and observing the rhythm of their hands. “The fabric carries its own pulse. My role is to listen to it,” she says. The resulting textiles are then studied, softened, or reinterpreted to inform new silhouettes. There is no fixed formula—her collections evolve from texture rather than trend. “Nothing about handweaving can be rushed. It follows its own tempo,” she adds.

At a time when all attention is on the crafts of India’s Northeast, Khiangte remains resolute that her work is more than representation—it is authenticity. “I don’t want to be seen as ‘the designer from Mizoram who does traditional textiles’; I want to be seen as a designer who happens to carry that heritage, and interprets it with honesty.”

With a vision grounded in craft, community, and courage, she says: “For Mizo textiles, my hope is to see them embraced not as ‘traditional craft’, but as living art that continues to evolve. You can honour where you come from without being confined by it.”

KINTEM

Meaning “communities” in the Ao-Naga dialect, Kintem is a reminder that clothing can be a form of belonging. Founded by Moala Longchar, the label is rooted in the belief that textiles are carriers of memory, connecting those who came before with those who will inherit the culture next.

In Dimapur, she grew up surrounded by yarns and looms because of her mother’s weaving business, though appreciation came much later. It was only after two decades away from home, working in Delhi, that she recognised the distinction and richness of Naga weaving, and the quiet familiarity of craft that had always been part of her life. Kintem was born from that moment of return—to identity, to material, to community.

The mekhala—traditionally wrapped and layered— becomes a contemporary statement at Kintem, softened in drape yet anchored in custom. “We reinterpret but not alter,” Longchar explains. The motifs remain sacred; it is their placement, scale, and the wearer’s context that evolve. Through new colours, shifts in proportion, and textile innovations, traditional symbols transform into global fashion while retaining their cultural integrity.

Weavers from multiple Naga communities contribute to the brand’s textiles, creating a mosaic of lived traditions. “Everything about Kintem is intergenerational,” she says. “So much of our work is shaped by the dialogue between me, my parents, and elders in the family.” The loin loom remains central, alongside experiments with banana fibre, nettle, indigo dyes, and cowrie details worked as extra-weft embellishments. These material explorations expand what Naga textiles can look and feel like, without distancing them from where they come from.

Preservation at Kintem is not traditionalism; it is a living process. With much of Naga textile knowledge undocumented and passed down orally, every conversation with elders becomes part of research. When preparing for a wedding collection, Longchar’s father mentioned the importance of betel nuts in traditional ceremonies—a detail that found its way into the tablescape of the bridal edit, Bonded. Tiny gestures like this become gentle ways of keeping memory active.

“Our textiles are our soft power. They serve as cultural bridges—contemporary yet never divorced from origin,” Longchar asserts.

Their debut collection, Inti—named after both a word meaning “everyone” and Longchar’s newborn nephew— reflects inclusivity not as branding but as identity. With textiles contributed by weavers from different tribes, the collection speaks of unity through difference, tradition through new beginnings. Meanwhile, Longchar’s professional experience in public relations has shaped a storytelling approach that allows the product and its community to remain the brand’s strongest voice. “Even someone with only a thousand followers can tell our story beautifully if they genuinely resonate with the brand,” she notes—a departure from conventional scaledriven marketing.

11 TARENG

In the northeastern city of Imphal, where handlooms still shape the visual rhythm of daily life, 11 Tareng is building a new vocabulary for Manipuri textiles. Founded by Jayshree Koijam and Reena Ahanthem, the label sits comfortably between the past and what’s next—quietly contemporary, yet unbothered by trends. Its language is textile-first, grounded in the region’s indigenous silks and weaves, and guided by the tactile wisdom of the women who have kept them alive.

The name itself—11 Tareng—speaks of motion and multiplicity. ‘Tareng’ translates to the spinning wheel while ‘11’ stands for the eleven tribes of Manipur—a subtle nod to the community-oriented foundation of the brand. “We wanted the label to represent balance,” says Koijam. “Between what is inherited and what is imagined, between process and purpose.”

At the centre of their work lies Khurkhul silk, a local material traditionally used for dhotis and phaneks (a wraparound skirt). Under their direction, it finds new form—in sharply tailored jackets, minimal skirts, and lehengas that carry the grain of the weave as a visible texture. Nothing is overdesigned; every piece lets the silk determine its fall. “Khurkhul has a beautiful stiffness and shine. It doesn’t need reinterpretation—only placement in a different context,” Ahanthem explains.

The founders’ sensibility comes from having grown up in the Imphal Valley, where weaving was not an act of preservation but a part of everyday life. Nearly every home once had a loom. “Even today, weaving remains a part of daily life and connects us to where we come from,” they add.

Inside the studio, Koijam and Ahanthem work closely with local weavers. “Every weave carries its own timing,” Koijam asserts. “You learn to listen to the loom, not direct it.” This patient rhythm translates into clothes that feel finished but unforced, each holding the quiet confidence of craft done with intent. “The idea has never been to change tradition, but to expand its possibilities,” the founders note. “Our culture has so much to offer—the beauty of the craft, the skill of the weavers, the stories in every thread. Through our designs, we’re simply giving these traditions a new space to exist.”

JENJUM GADI

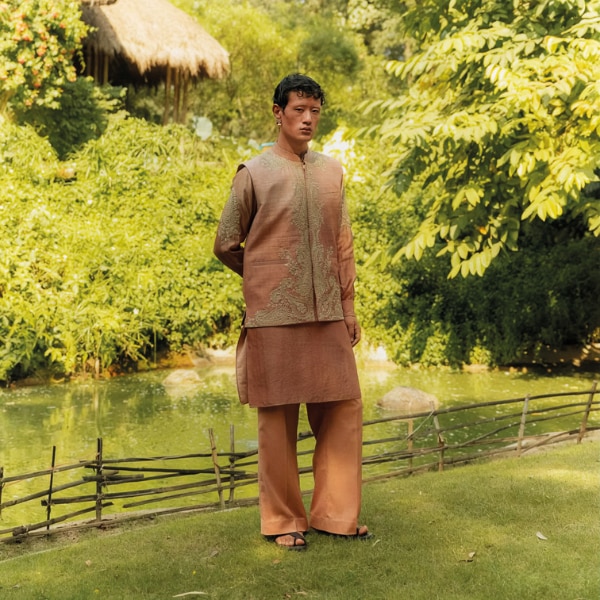

For years, Jenjum Gadi has been steadily expanding the vocabulary of Indian menswear. His approach is rooted in the fundamentals—thread, weave, and structure— reflecting a steady dialogue between his Northeastern roots and an urban, modern vocabulary.

Coming from Tirbin, Arunachal Pradesh, Gadi’s creative world was shaped by the textiles and rhythms of home. “Growing up in Arunachal Pradesh, I was surrounded by colour,” he recalls. “If you see our Northeastern textiles, they’re very bright, full of life. So when I started working with menswear, which usually leans towards more muted tones, I already knew how to balance both worlds. I could take risks with colour because I understood how to make them work together—how to mix traditional patterns with contemporary cuts and create something unexpected.” he says.

That understanding defines his design language—the way he layers, drapes, and builds rhythm on fabric. Every piece starts with handspun or handwoven textiles, which he treats as a base to construct something new. “Nature inspires me deeply,” he shares. “There’s texture, depth, and even imperfection in it and that’s what makes it beautiful. I don’t like flat surfaces or plain garments. That’s why I mix embroidery, patching, and even origami-like folds. It reflects who I am and where I come from. I might use a textile from Assam and combine it with embroidery from Rajasthan or Kashmir. For me, it’s about carrying my past into my present and pushing it into my future,” he adds.

He tells me that the turning point in his journey came in 2015, when he took a break from fashion. “That break really helped me relook at everything that I wanted to do and how I wanted to do it. The industry had become too fast, too instant. I didn’t want to chase that pace anymore. I wanted to create something slower, more meaningful. I wanted to enjoy the process again,” he says. His voice softens when he talks about his journey. “I’ve learned not to rush. My path from a small village to Delhi exposed me to so many different cultures. It taught me that I don’t need to fit into what fashion expects—I just need to keep it honest,” he asserts.

In recent years, his silhouettes have softened into universality—free-size, unisex, designed to move between spaces and identities. “People are smarter now when they buy, it’s about mobility and expression,” he explains.

As we speak, his thoughts keep returning to home—to the weaves, patterns, and tribal motifs that shaped him. “The Northeast has so many tribes and each has its own embroidery language. When I draw from them, I don’t pick one motif and repeat it. I reinterpret them, combine them, and create something new. That’s how you keep tradition alive—not by freezing it, but by letting it evolve,” he says.

All images: The brands and Instagram

This article was originally published in the November 2025 print edition of Harper's Bazaar India

Also read: Ten iconic intersections between fashion and literature

Also read: Met Gala 2026 theme revealed: “Costume Art” ushers in a new era at the Met