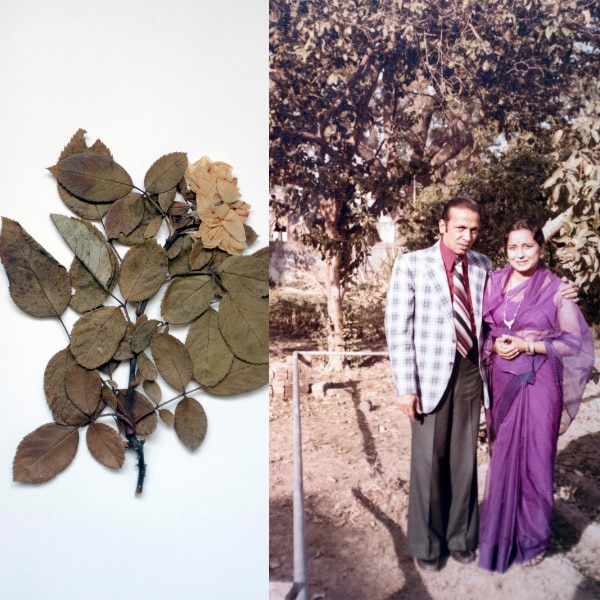

My grandma wore linen before it was cool

A visual essay on wear, ritual, and memory.

WHAT WAS FOLDED, STAYED FELT

Every morning in my grandmother’s house began with the rustle of fabric. She would lift a linen sari from the chair, still carrying the heat of the iron, and fold it neatly before the day started. The room smelled of rose powder and starch mixed with the faint scent of coconut oil from her hair. Her clothes grew softer with each wash, the edges fraying just enough to show use, not neglect. Inside the wooden cupboard, every fold seemed to hold a trace of her patience, the way years of small, careful gestures can turn routine into devotion.

SOFTNESS IS THE NEW STATUS SYMBOL

In India, softness was never a fashion choice. It came from the way people lived with their clothes. Linen and cotton were worn for air, for sweat, for work that lasted the whole day. A kurta turned supple after a dozen rinses, a sari grew lighter with every monsoon. The fabric learned its wearer, not the other way around. Before softness became a marketing word, it was simply what time did to a good cloth. When the world discovered the appeal of lived-in texture, India had already spent generations washing, sunning, and folding it into second skin.

A CREASE IS A MEMORY TOO

What we now call design often begins in repetition. The folding, washing, and rewearing that shaped Indian wardrobes were small but deliberate acts of calibration. Over time, those habits turned into a way of seeing the form of how fabric drapes, how colour fades, how a crease settles. Modern design in India still borrows that patience, translating maintenance into method. The aesthetic isn’t borrowed from the West; it’s inherited from care itself. A well-worn sari or softened kurta already solved the problem that fashion keeps chasing— of how to make something new feel like it has already lived.

THE HISTORY WAS ALWAYS IN THE WEAVE

In the early decades of industrial India, linen was seen as too demanding for machines and too stubborn for mass production. It had to be handled slowly, spun by hand, coaxed into thread that could survive heat and humidity. Khadi carried a similar patience, built on the same resistance to speed. When the freedom movement turned handspun fabric into a political symbol, it was less about purity and more about preservation of skill, labour, and the closeness to material.

TEXTURE TAUGHT THEM EVERYTHING

People learned to read fabric the way others read weather like how humidity changed the fall of a sari, how sunlight revived dull cotton. That sensitivity to material taught a slower logic of living. You couldn’t rush a garment into comfort; you had to earn it through use. The patience that kept clothes intact often extended to everything else like food, relationships, rhythm. What endured was not just the cloth but the temperament it required. To touch something daily, to mend and rewear it, was to practice steadiness in a world that kept moving faster.

THE BLUEPRINT WAS ALWAYS HERE

Every generation rediscovers what the last one never forgot. The world now speaks of sustainability and slow fashion, but Indian households have always practised it without ceremony. Clothes rotated with the season, stitched when they tore, shared when they no longer fit. Linen carried inheritance better than silk ever could because it allowed for change as it softened, adjusted, and survived. We are tracing our steps back to a wisdom that never vanished, only went silent.

All images: Kannagi Khanna

This article was originally published in the November 2025 print edition of Harper's Bazaar India

Also read: Ten iconic intersections between fashion and literature

Also read: How Roshan Raju is making AI feel human: The story behind Imersive