In praise of the cathartic power of a good cry

Crying is scientifically proven to reduce stress—so why do we still try and hold back tears?

Thanks to the Public Displays of Emotion Act of 1831, it is illegal to cry in public in Great Britain. And while, of course, I’m being facetious, for many Brits, not crying is a badge of honour. You ran over my beloved pet? He peed on the carpet anyway. Somebody stole your brand new iPhone the day after you bought it? No worries. A hangover from the Victorian era, when stiff upper lip propaganda like Rudyard Kipling’s ‘If–' was popular, stoicism in the face of adversity has become firmly ingrained in the national consciousness.

Yet in recent weeks, we’ve seen a lot of crying in public. Most notably, we had the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Rachel Reeves, caught crying during Prime Minister’s Questions last month. Then there was defending Wimbledon champion Barbora Krejčíková, who audibly broke down and began sobbing loudly during her third-round game against Emma Navarro, in which she was ultimately knocked out of the competition. The pop star Katy Perry has been crying on stage following her break-up with Orlando Bloom; Aimee Lou Wood was papped with teary eyes amidst the hullabaloo of the SNL skit drama (though she explained it wasn’t actually to do with that); and even Love Island's Harry Cooksley has shed a tear over his questionable actions in the Mallorcan villa.

And while reactions to each of these incidents have been myriad and complex (Reeves, as a politician, and crucially, a woman, perhaps bearing the brunt of a lot of misogyny and unfairness), they all go to support my theory that there is nothing better, or more cathartic, than a good cry. You see, I’m a big crier. I cried when I missed my train connection because I was looking at the “Arrivals” rather than “Departures” board. I cried when I burned the top of a steak pie I’d been looking forward to eating all day. I’ve even cried at McDonalds adverts on TV. I’m the opposite of Cameron Diaz’s character in The Holiday—though I do share her taste in Jude Law.

Lucky for me then, that crying is scientifically proven to relieve stress. “Unlike basal tears, which are continuously produced by the tear glands to keep the eyes lubricated, or reflex tears, which are triggered by irritants like smoke and contain about 98 per cent water, emotional tears are thought to carry elevated levels of stress hormones,” explains Dr Enone McKenzie, Consultant Psychiatrist at The Soke. “When we cry emotionally, chemicals such as oxytocin and endogenous opioids (endorphins) are released in the body, helping to relieve both emotional and physical pain.” Your tears are literally little stress rivers leaving your body.

And while it might seem obvious that crying is good for our long-term mental health, it’s also got benefits for our physical health, too. “Crying serves as an important mechanism for emotional regulation,” continues Dr McKenzie. “Suppressing or avoiding emotional expression—a strategy known as repressive coping—has been linked in research to adverse health outcomes, including dysregulated immune function, elevated cardiovascular risk, and increased vulnerability to psychiatric conditions such as anxiety and depression.” Crying also bonds us and, crucially, can make you more likeable (unless you’re a politician). That’s why the specific pitch of a baby’s cry cuts through the heart of its mother. “Parasocial relationships thrive on the illusion of intimacy and visible tears can strengthen that illusion by lowering apparent emotional barriers,” says Dr McKenzie. “This can deepen emotional investment in the parasocial bond and build loyalty, leading to continued engagement or support. Furthermore, crying can play a key social role by enhancing attachment behaviours, signalling vulnerability, and eliciting empathy and supportive responses from others, which can strengthen social bonds and promote interpersonal connection.”

One famous example of this is when Andy Murray cried in 2012 after he lost the Wimbledon final to Roger Federer. As he wiped away tears and emotionally told presenter Clare Balding, “I’m getting closer”, the nation’s opinion on the until-then morose Scotsman did a complete 180, as we firmly accepted him as one of our own. There was even a hint of sympathy for the former Prime Minister Theresa May a few years later when she broke down during her resignation speech—ditto so-called ‘Iron Lady’ Margaret Thatcher some decades earlier. And it can also be a collective experience too—something which bonds us as a nation—with perhaps no better example of this than the collective outpouring of grief surrounding the death of Diana, Princess of Wales, a woman that the vast majority of the public had of course never met. A nation of stiff upper lips? Please.

Ultimately, crying is one of the most basic and essential communication tools that we have. As Charlotte Brontë famously wrote: “Crying does not indicate that you are weak. Since birth, it has always been a sign that you are alive.”

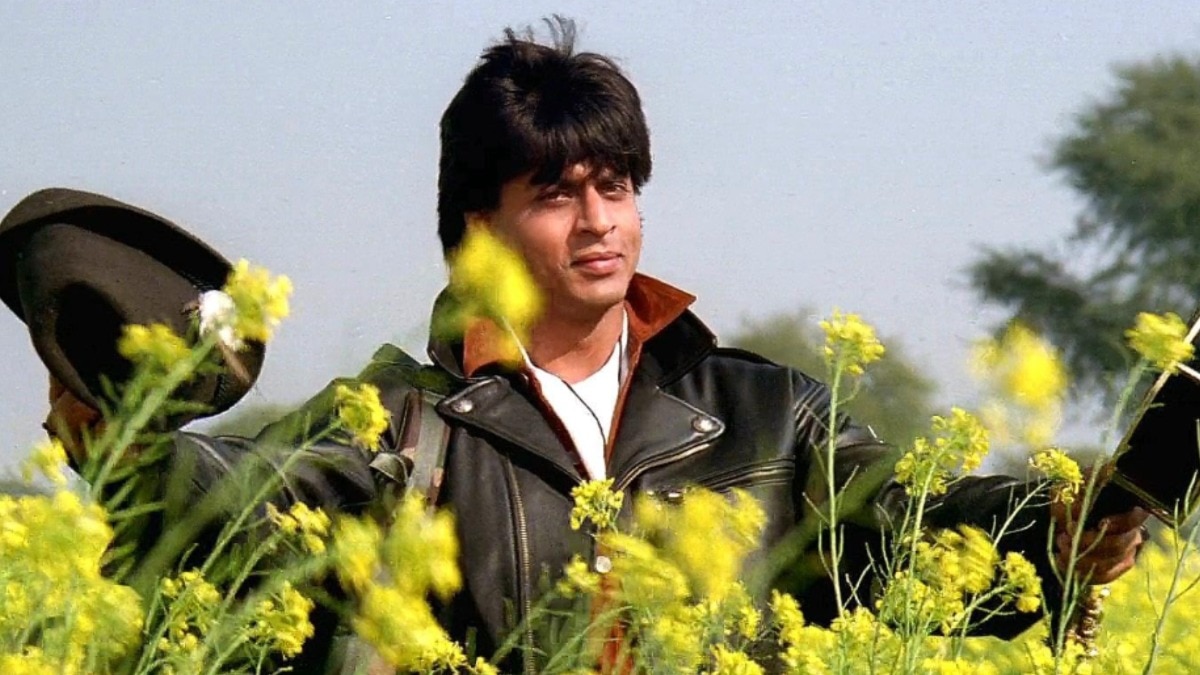

Lead image: Film Vip Medienfonds/Kobal/Shutterstock

This article originally appeared on Harper'sBazaar.com/uk

Also read: Are micro-routines helping us truly rest or just survive?

Also read: Inside the mindset shift that’s helping women take charge of their financial futures