How Sonia Boyce has been staging a quiet revolution from within the British art world since the 1980s

Propelled to international success at this year’s Venice Biennale, she is connecting communities and building bridges.

"Watch out—there’s glitter everywhere!" warns Sonia Boyce as we file into her compact, light-filled studio inside a 1930s block in the heart of Brixton. The artist has been making a series of gilded geometric sculptures—similar to those that were unveiled in her Golden Lion-winning British Pavilion at the Venice Biennale earlier this year—and everything that surrounds us is lightly dusted in gold.

Boyce certainly seems to have the Midas touch: Her victory at Venice marks the latest in a long line of against-the-odd triumphs that date all the way back to 1987, when—aged just 25—she became the first Black British female artist to enter the Tate collection (the museum acquired her watercolour, pastel, and crayon drawing Missionary Position II, which explored themes of religious oppression). Yet her road to stardom has been neither straight nor straightforward; rather, she describes this year’s win as the reward for a kind of gritty perseverance that has seen her through good times and bad. "It’s a validation of the things I’ve been ploughing away at, sometimes with certainty, but with uncertainty as well," she says, with the quiet thoughtfulness that characterises all her speech. Whereas in her twenties she was barely able to grasp the significance of Tate’s acquisition of her work—"I was too young to comprehend what that meant, too young to know it was even a thing"—this time round, she has found herself more conscious of why her success matters to minority artists everywhere, whether they are female, Black, or simply pushing against the status quo. "On the day of the opening, I really did understand the weight of history...though I’m not quite sure I know what to do with that at the moment."

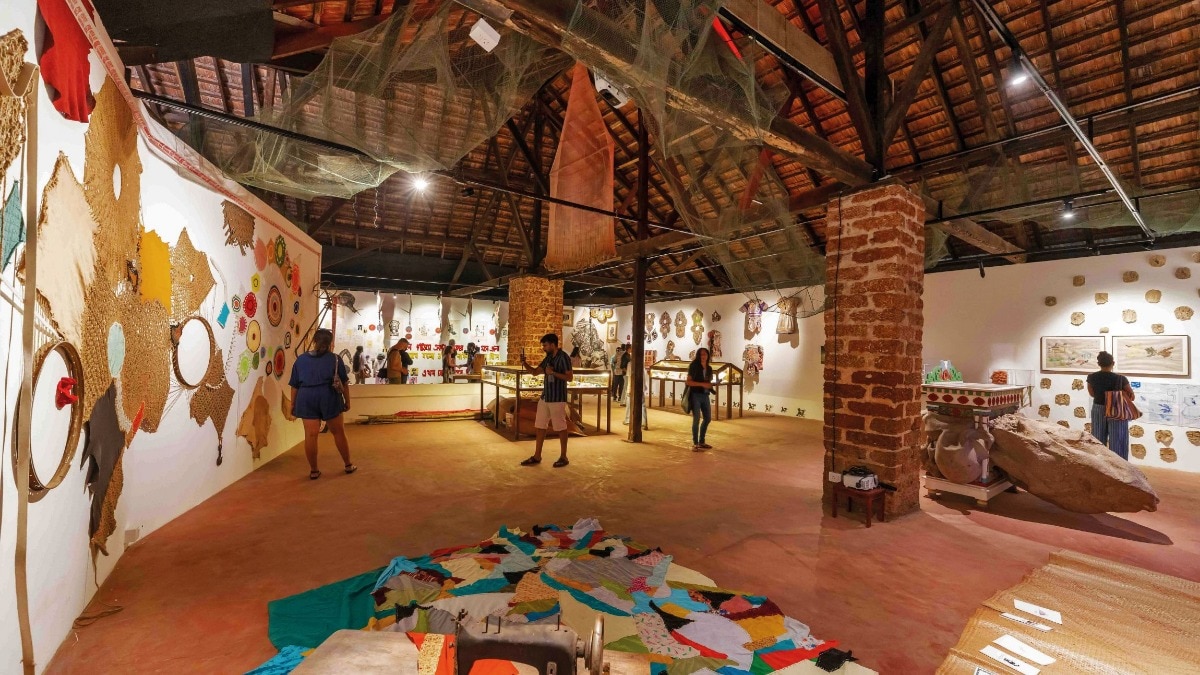

Burdening any artist with the responsibility of representing a particular community is unfair, and yet a sense of community is precisely what pervades Boyce’s work, in all its joyful, cacophonous togetherness. For her Venice installation, she enlisted the talents of five Black female musicians (Jacqui Dankworth, Poppy Ajudha, Sofia Jernberg, Tanita Tikaram, and Errollyn Wallen) to record improvised performances at Abbey Road Studios, which she then edited into 10 films that were broadcast simultaneously across the five spaces of her Pavilion. "I’d always wanted to create my own girl band—but a girl band that doesn’t necessarily play by the rules," says Boyce, with a twinkle in her eye. The performers had not met until they arrived at the studio, and all but one had never improvised, so there was no guarantee the concept would work—but it is perhaps that element of risk that gives a particular frisson of excitement to the recording. As Boyce explains, "I purposely don’t direct anything I do. I just say, 'This is the space, this is what we have available to us—let’s see what happens'." Titled Feeling Her Way, the resulting work is a celebration of the beauty that comes from spontaneity, and the collaborative nature of its creation feels particularly resonant in the wake of the pandemic. "One of the things I thought about during the lockdowns was how we might be able to re-engage emotionally with one another," says Boyce. "There’s something about music that just cuts straight to the heart—I want people to come to the Pavilion and feel a connection, even if they can’t quite describe what it is."

Walking through the installation is an extraordinary multisensory experience. Not only are visitors bathed in a unique soundscape, but they are also surrounded by an exuberant mix of ephemera: tessellated wallpapers, collages of CD, cassette and album covers, posters and photographs, and more of the glistening sculptures spotted in Boyce’s studio, inspired by a mineral known as pyrite, or ‘fool’s gold’. Each element references the artist’s particular interests: the wallpapers, for instance, reflect her long-standing fascination with William Morris, whom she calls "the most supreme geometrist—he takes what we know of the outside world that’s wild and dangerous, and he introduces it into the home in a way that makes it safe. That’s what repeat pattern does—it brings order to something chaotic." The same is true of her own work, which has uncertainty built into the process, and yet somehow culminates in harmony and completeness. "To work with improvisation is to invite the possibility of chaos," she admits, "but my immediate response is always to appease that." She describes her artistic process as "peripatetic", involving a mix of time in the studio and exploring beyond it. "I need to go out and engage with people, and then I’ll bring back whatever comes from that, and try to process what it is and what I can do with it."

Boyce’s instinct for sorting and ordering, for drawing out the golden threads from a mass of different ideas, has served her well in her long, and committed career as an art teacher (she is currently a professor at the University of the Arts London, and previously ran a first-year fine-art course at Goldsmiths, with Gillian Wearing among her students). "Being in an environment where everyone’s trying to figure out what they want to do has really supported my practice," she says. "For a long time, I think the idea of being a teacher as well as an artist was rather looked down on—and of course, it’s exhausting sometimes, but it can also give a lot."

Her determination to nurture the next generation of artists with empathy and open-mindedness is, in part, a response to her own disappointing educational experience. "It took me a long time to get over art school," she says of her three years at Stourbridge College of Technology and Art in the early 1980s, where the curriculum focused on a male-dominated canon and the teaching was heavily skewed towards abstract art, which happened to be in favour at the time. "I was quite resistant to the idea that there is a particular way to make art, and that other ways of making art are somehow redundant or irrelevant, or just shabby. I got quite angry about the insistence on a certain doctrine... I suppose I still have that feeling."

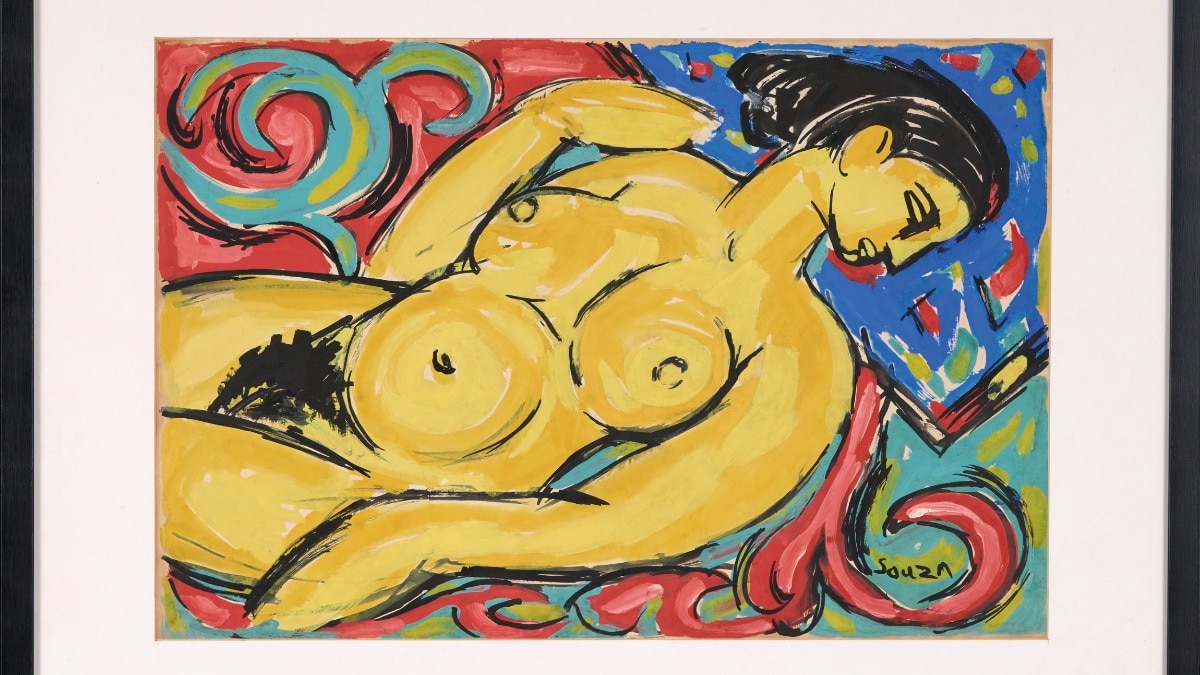

An early epiphany for Boyce came in 1982, when she attended a conference for Black artists at Wolverhampton Polytechnic; the sense of camaraderie in the room was a tonic for her mounting frustration with the establishment. That gathering proved to be a significant moment in British art history, prompting the emergence of a radical political movement advocating the work of Black artists that spread from the West Midlands to London and across the country. Boyce—who by her own admission had thought she "would just go back to working in a shop" after graduating—became something of a darling of the art world, achieving renown for her chalk and pastel drawings exploring themes of domesticity, heritage and belonging. Her Frida Kahlo-inspired 1986 work She Ain’t Holding Them Up, She’s Holding On, which conveys the artist’s dual identity as a Black British woman and a second-generation descendant of Afro-Caribbean immigrants, was particularly well received, with its references to English roses and William Morris-style patterns.

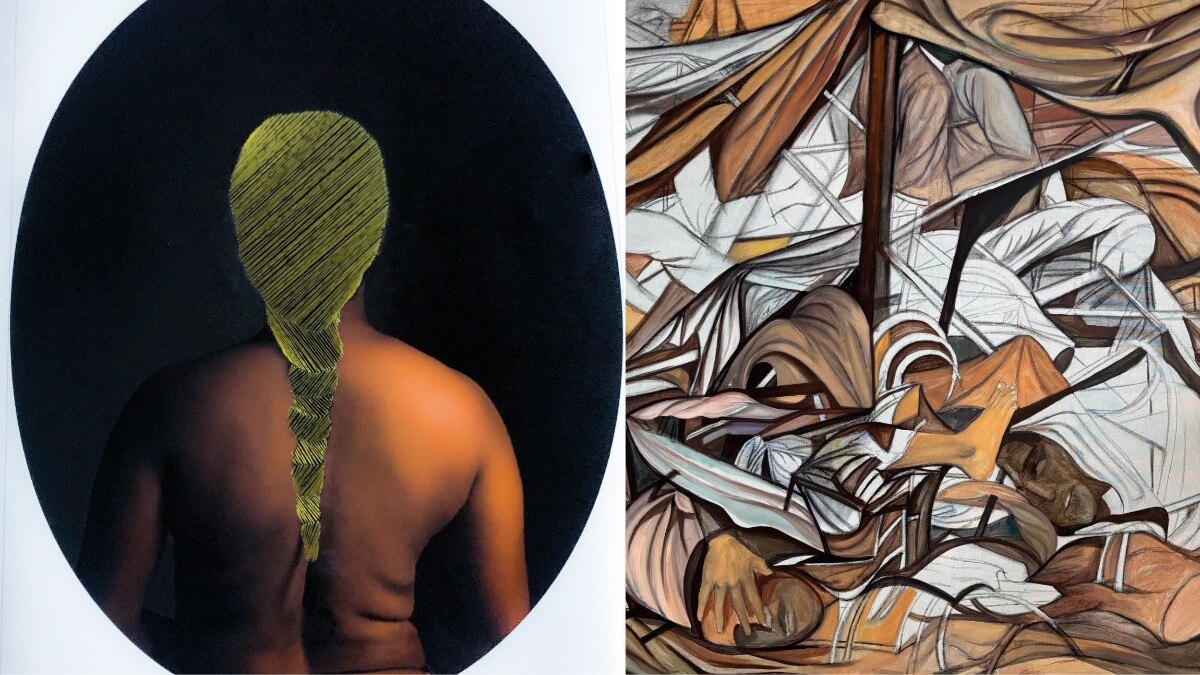

Towards the end of the 1980s, however, Boyce began to feel restricted by being her own subject, and gave up figurative drawing in favour of less autobiographical, more performative work that challenged traditional definitions of what an artist should or could do. Among her pioneering collaborative endeavours were the 1997 piece The Audition, for which she photographed hundreds of members of the public trying on Afro wigs; and her seminal—and ongoing—Devotional project, which began in 1999. Boyce challenged a small group to name a Black female singer they loved (after a somewhat pregnant pause, they came up with Shirley Bassey); more than two decades on, she is still collecting names for her ever-growing catalogue, which she has shared with the public through prints and photography, wallpapers and placards, and even Spotify playlists. Her Venice Pavilion is, in many ways, the culmination of that ambitious undertaking; a forum to celebrate some of the musicians from her collection in front of her biggest audience yet.

Much of Boyce’s recent art seeks to give a voice—sometimes quite literally—to underrepresented communities: earlier this year, she made a poignant contribution to the Serpentine’s group exhibition, ‘Radio Ballads’, that highlighted the vital role care workers play in preventing domestic abuse and supporting victims. And ahead of the recent opening of the London Underground’s Elizabeth Line, she unveiled a 1.9-kilometre artwork, Newham Trackside Wall, made up of printed panels that showcase the experiences of local residents in one of the capital’s most deprived boroughs. "Sometimes I think there’s an almost comic-book-style understanding of what working-class life in London is like, and I wanted to give a fuller picture, to hear from people who might not normally be heard," she explains.

Perhaps her urge to provide a platform for others comes from a lingering sense of disbelief that she herself now has such a powerful one. Boyce tells me of her surprise that the British Council, which commissioned her for the Venice Biennale, was aware of her work ("I didn’t know I was even on their radar"), and describes her monumental achievements as the result of good fortune rather than intention. "My journey has really been about unanticipated moments, because when I came out of art school, there wasn’t a roadmap for someone like me," she reflects. "Now, I think artists are able to set out their stall and have some understanding of what they want to achieve, which is brilliant. It’s about time, frankly." She is optimistic about the future of the art sector as it opens up to an ever-broader spectrum of creative people and ideas. "When I was a student, being introduced to feminist art practices was a revelation, and now it’s just not so much of an issue, because there are more of us around. The same goes for artists of diverse backgrounds," she says. "I really do think we know when something’s not right, and when it’s getting to be right... Humans are irrepressible." So, evidently, is Sonia Boyce.

This piece originally appeared in the print edition of Harper's Bazaar UK.

Feature image: cultureshockit/Instagram

square image: lepinayangelique/Instagram