Fifty years since Sholay released, Javed Akhtar reflects on the enduring legacy of the cult classic

Harper's Bazaar chats with the writer and lyricist on what it takes to make burnished gold.

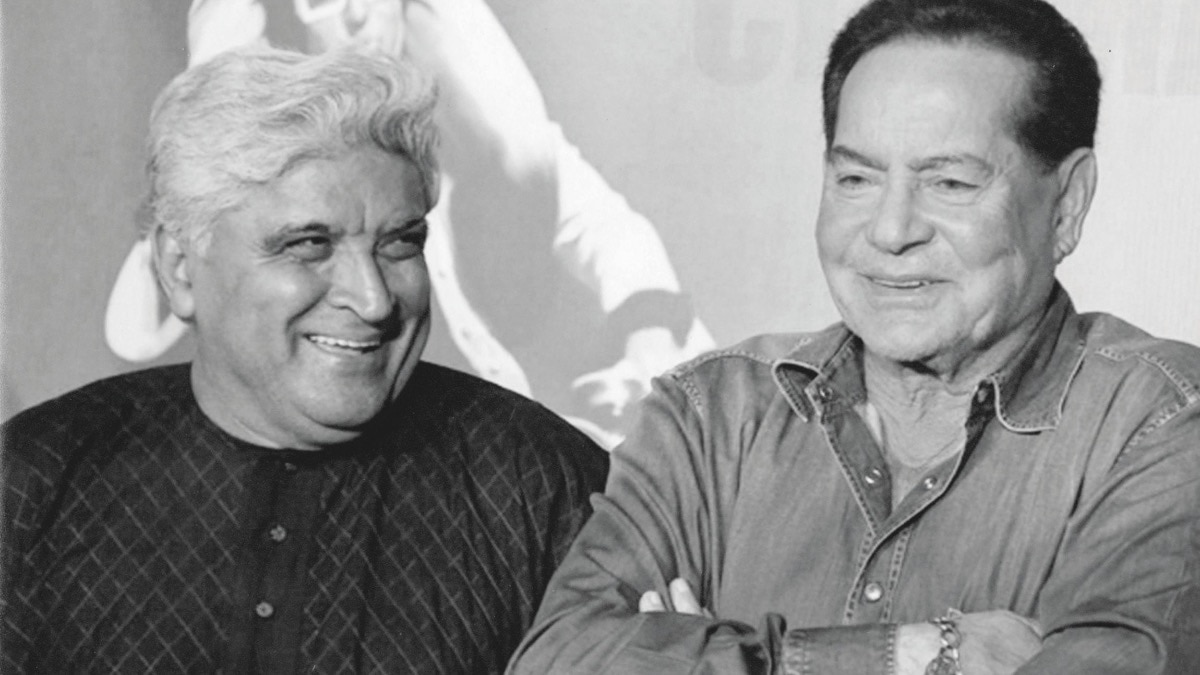

I join our Google Meet link 10 minutes early, nerves coursing through me. No amount of Googling can prepare you to greet a true legend—something my father reminded me a thousand times the night before. As I channel my cold feet into frantic texts to my mother, my screen shifts—and there he is. Javed Akhtar, punctual to the minute.

His snow-white hair is neatly parted, a soft pink kurta drapes effortlessly over his frame, and joyous mischief sparkles in his smile. Behind him, uncountable pitch-black Filmfare trophies line the shelf—a sight that humbles even the toughest hearts. His warmth puts me at ease, his humour has me in splits every 15 minutes,and his humility proves I am in the presence of true greatness.

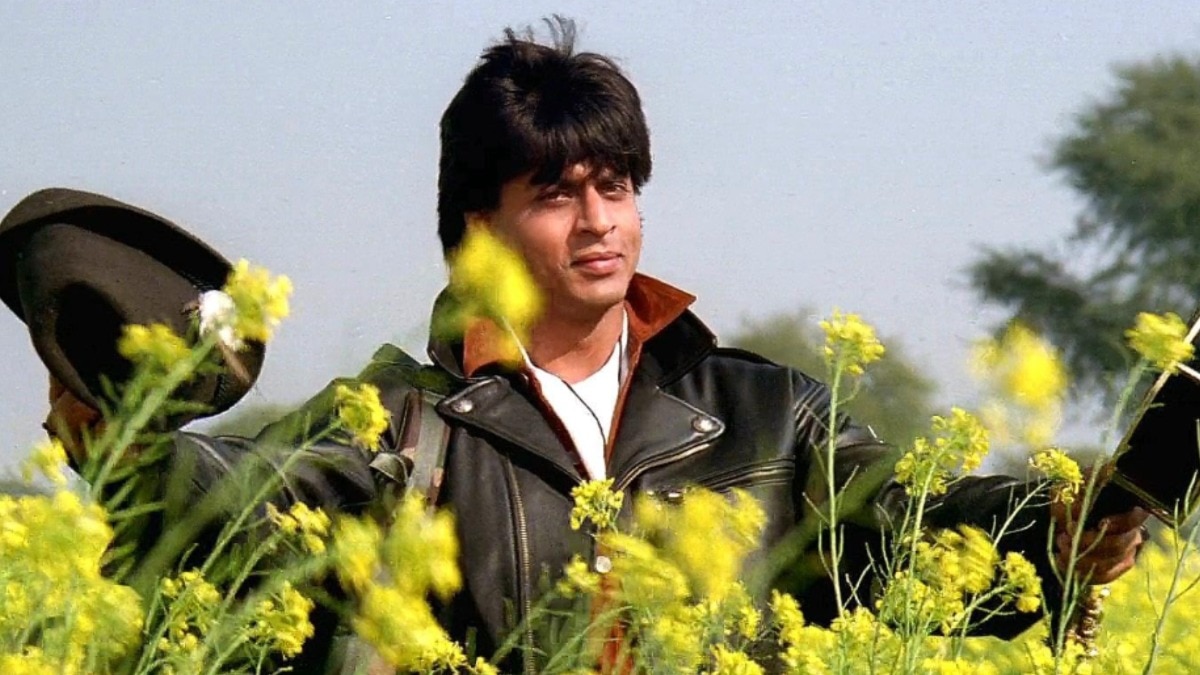

Few films in Indian cinema command the reverence of Sholay. Initially dismissed upon release in 1975, it has since become a timeless milestone, transcending generations. I first watched it at 14, along with my parents, who bonded over their shared love for the film (and its leading men) in the early years of their arranged marriage. Its characters, dialogues, and storytelling remain unmatched,deeply embedded in India’s cultural fabric.At its heart stand two visionaries—Salim Khan and Javed Akhtar—whose words gave Sholay its soul.

Akhtar speaks of the film’s origins with affection. Sholay was not conceived as the grand spectacle it became. Initially, it revolved around a retired Army major who hires two court-martialled recruits to avenge his family. It was producer GP Sippy who suggested replacing the Army backdrop with the police force, allowing greater creative freedom.“There was no deliberate attempt to make it a mammoth, multi-starrer film,” Akhtar reveals. “But as we fleshed out these characters, they naturally took on a life of their own.”

Despite a formidable script, casting was no simple feat. Dharmendra and Hema Malini were natural choices, but the role of Jai was fiercely contested.While industry heavyweights vied for the part, it was Amitabh Bachchan—then yet to attain super stardom—who was championed by Akhtar and Salim Khan. “The trial screening of Zanjeer (1973) convinced Mr Sippy. The rest, as they say, is history.”

If Sholay were a grand symphony, its darkest, most unforgettable notes belonged to Gabbar Singh. Filmmaker Pratim D Gupta recalls watching the film as a child and being struck by Gabbar’s cold-blooded nature. Anupama Chopra, Editor of The Hollywood Reporter India, and author of Sholay: The Making of a Classic (2000) also remembers “being afraid of that eerie background music” that played every time Gabbar came on screen, when she first watched the movie as a nine- year-old.

Interestingly, Akhtar proceeds to relate the story of the iconic villain’s almost accidental casting. Amjad Khan, an untested actor at the time, was Akhtar’s choice, having seen him perform in a stage play during a university tournament. “We had decided on Danny Denzongpa, but there was a clash of dates. That’s when Salim saab suggested Amjad’s name, after hearing me rave about his talent for months.” An audition was arranged, and the moment the first line was read, the makers knew they had found their villain.

Gabbar wasn’t merely a dacoit; he was a force of nature, an omnipresent spectre of terror and cruelty. “Writing his dialogues was an experience unlike any other,” Akhtar reminisces. “It was as if Gabbar himself was revealing his words to us. We, the writers, were merely witnesses.” The menacing cadence of “Kitne aadmi the?” stands uncontested in cinematic villainy.

For all its action-packed bravado, Sholay remains a film about friendship.The relationship between Jai andVeeru set a new benchmark for male camaraderie. Gupta recalls craving a friendship like that, in his school days. “The energy between Jai and Veeru was infectious,” he adds. Akhtar acknowledges this as a deliberate writing choice. “We wanted it to be real,” he explains. “The strength of their friendship lay in their actions, not overt declarations.”

Equally remarkable was the film’s use of silence—especially in Jaya Bachchan’s portrayal of Radha. I point out her grief and yearning for Jai looms as a haunting melody over the film—something my mother insisted I note, the first time I watched the film. “No words can convey what silence can, if used correctly,”Akhtar asserts. “It invites the viewer’s imagination to fill the gaps, making the emotion more powerful.”

Remarkably, Sholay was almost dismissed as a failure. Trade analysts predicted doom, calling it too unconventional.Yet, the faith of its creators never wavered. “We were convinced it would be a hit,”Akhtar says.“What we didn’t anticipate was that it would surpass every expectation.” Indeed, Sholay went on to break records, running in theatres for years. More importantly, it became a cultural lexicon. Its dialogues entered everyday conversations, and for the first time, producers took stock of the indispensable nature of writers in filmmaking.

The film’s appeal cut across class and geography—it belonged to the masses as much as to cinephiles. Reflecting on its 50-year legacy, author and film critic Prathyush Parasuraman says, “I think it is in the celebration of friendship, the iconic image of bike and sidecar, used again in Munnabhai, which softens the hard masculinity of the bike with a joyful appendage.” For Akhtar, it is the film’s offering of human emotions that makes the cut. “It is a complete work of storytelling, where every chord strikes a deep, lasting resonance.”

New generations continue to discover Sholay’s magic, proving true cinematic brilliance is rarely ‘writ in water’ in the Keatsian sense of the term. “Twenty-five years ago, when I was writing the book, Shekhar Kapur said Indian cinema can be divided into Sholay AD and Sholay BC,” says Chopra of the film, which she also labels as her forever favourite, and the defining gift of Hindi cinema that keeps on giving.“It was instinct that led us to write it the way we did,” Akhtar muses. “Looking back, we realise that it was perhaps destiny.”

This article first appeared in Bazaar India's March-April 2025 issue.

Image credits: Javed Akhtar and IMDB.com

Also read: This Kolkata-based exhibit gives a rare glimpse of the lesser-known textiles of West Bengal and Bangladesh

Also read: Power lifting made me a better writer