All the ways I lost my best friend

Friendship breakups don't have to be big and dramatic. Sometimes, they are a slow process of coming apart over time.

When I found out I was pregnant the same week my friend E. gave birth to her first child, I pictured our children growing up side by side.

We lived five stops apart on the same subway line in Brooklyn and had known each other for more than a decade. Over the years, our friendship had spanned moves across three continents (mine), survived a broken engagement (hers), and endured a mutual ex-friend who was hellbent on destroying us both. We had been constants in each other’s lives, even as the shape of those lives changed. I imagined a future of park dates and playground mornings, our children forging a friendship as naturally as we had.

But life didn’t follow the script I had envisioned.

We met up occasionally in the park, or for coffee in the rare windows when neither of us was working and both babies were awake. She had Mondays off, when I was buried in work. I was free on weekends, when she was often hosting openings or out of town. Even when our schedules aligned, our children’s naps rarely did. Fitting time together became a feat of logistical acrobatics.

It wasn’t that we didn’t try. I visited E. the weekend her daughter was born, and she came to see me when my son arrived, bringing pastries and coffee to my bedside. I showed up to her gallery openings; she was by my side when the play I produced premiered. She took me out for my birthday; I sat with her when her mother died. But gradually, we drifted to the margins of each other’s lives.

I watched, in that toxic, self-destructive way the internet allows, as her life filled with other people - new “mom friends” who had the flexibility to drop by her gallery in the middle of the day, wives of her husband’s friends with whom she went away on weekends. For years I wrestled internally with the contradiction: that E. and I still cared deeply for each other, yet we no longer occupied central space in each other’s worlds.

Often, I blamed this state of affairs on her husband, whom I had never fully connected with. Other times, I wondered if in blaming him, I was letting E. off too easily. Surely, she had a say in who they hung out with on weekends, too. At times, I wondered if I was delusional about the state of our friendship, imagining a closeness between us that was no longer there. Other times still, I felt ashamed of my pettiness and greed: that what E. and I had, as much as it was, wasn’t enough for me.

All of these things were probably true, to some degree. But over time, I came to realize that there was something else at play, too - something that went far beyond the particulars of E.’s and my friendship.

In my late teens and early twenties, my friendships had been intense and explosive, burning bright but often flaming out in a few years. As I grew older and wiser, better at navigating the inevitable small conflicts that come with truly knowing another person - and better at choosing friends in the first place - this pattern gradually petered out, and the friendships that survived my twenties solidified as the most cherished relationships in my life.

What I didn’t understand then was that the next stage of life would come with its own threats and vulnerabilities: lack of time, shifting priorities, and the challenge of maintaining relationships with people you care for deeply, but who no longer easily fit into your life.

I did not understand that friendships could die not only because of impassioned fights and mutually unforgivable trespasses, but because of shifts in circumstance, waning effort, and the cumulative weight of small hurts.

The drift between E. and I didn’t start with motherhood. In our 20s and early 30s, we were both scrappy artists trying to cobble together careers in competitive and poorly paid fields. But by our mid-30s, our lives had begun to diverge. Her world became members-only dining clubs, luxury hotels, weekends in the Hamptons. Mine was bookstore readings, political debates, and dinner parties in my apartment, surrounded by artists, writers, and activists. I found her new friends superficial; she thought mine were boring.

At first, I pushed against our growing distance. I felt sad and unsettled that she had a whole new life I wasn’t - and couldn’t - be a part of. But when I tried to bring her into my world, things felt just as misaligned. It was only when we were alone that our friendship still made sense. In the presence of others - be they our friends, our spouses, or the new people who had begun to fill the spaces we had once filled for each other - we no longer quite clicked.

Then, during the pandemic, E. moved to Los Angeles. We still spoke occasionally, but the scaffolding that had once held our friendship - weekday lunches, gallery openings, a shared city - was gone. Without proximity, the cracks we’d both been papering over became more difficult to ignore.

E. would call in the middle of a workday, and I wouldn’t always pick up. When we did talk, it felt effortful, more like performing closeness than inhabiting it. She visited New York without telling me; I’d find out only through Instagram Stories. I was hurt, and also complicit. For my 40th birthday, I planned a trip with friends but didn’t invite her until the last minute. We were holding onto the shell of a friendship, not the living thing it had once been.

Eventually, the quiet ache became too much. After another trip to New York where she didn’t reach out, I sent a long, emotional email - trying, maybe clumsily, to articulate the sadness I’d been carrying. I told her I loved her, but I didn’t know how to keep pretending things were the same. That I needed some space - from the sadness, from the performance, from a friendship that no longer made room for who we’d become.

Almost immediately, I regretted it. The message felt adolescent, overdramatic - a return to a version of myself I thought I’d outgrown. And I think it struck her that way, too. But when we spoke a few days later, we were both kind. E. was surprised - I don’t think she had realized how far we’d drifted. I apologized for dropping an emotional bomb on her and told her that I hadn’t known another way to bring up what I was feeling. I hadn’t wanted to just suddenly stop returning her calls. I needed space, and she understood. She told me she loved me, and that she’d still be there.

We never officially broke up. But something shifted. The air cleared.

It’s tempting to frame what happened between E. and me as just the inevitable drift of midlife - careers, families, and the sheer exhaustion of daily life pulling us in different directions. But that would be too simple. If we had truly wanted to stay close, we would have made different choices. She could have invited me on one of those weekend trips instead of always choosing her new friends. I could have picked up her calls in the middle of the day instead of letting them go to voicemail.

And yet, even as we drifted apart, we never truly disappeared from each other’s lives. When my mother died, E. wasn’t there in person, but she was there digitally - watching the funeral online, sending messages that were exactly what I needed to hear. Later, when I returned to New York, she sent flowers with a note saying my mother would have been proud of me. It was the type of kindness that comes from history - the kind of friendship where you don’t need constant contact to be there when it matters.

Last year, I saw on Instagram that E. was back in New York, celebrating the birthday of one of the friends who had been able to hang out in the gallery during the day back in those early years of motherhood. This time, I didn’t feel upset. I finally felt at peace with the way our friendship had evolved.

Friendships aren’t necessarily meant to last forever in the ways we first imagine. They change because we change. I used to think I was past the point of friendships ending. But no friendship is entirely safe from change. And while we might mourn what’s lost, it doesn’t erase what once was - or what still is. E. and I may no longer be best friends. But our friendship still lives - smaller, quieter, softened by time - and still, somehow, full of love.

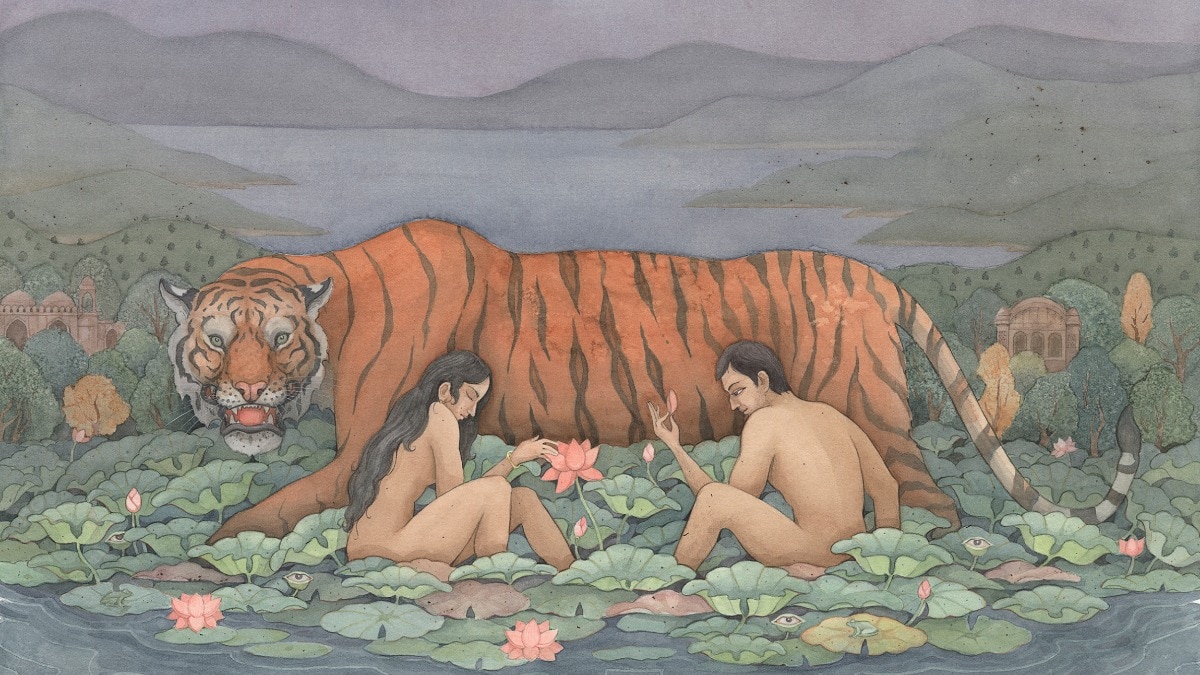

Lead image: Hearst Owned

This article originally appeared on Harper'sBazaar.com

Also read: How cycle syncing is changing fitness and food

Also read: Get ready for alt-girl summer