Women love to wear this 1950s silhouette to work—but why?

A tantalising Venn diagram of regression, femininity, and freedom.

“POV,” wrote 23-year-old Hannah Wu in a TikTok posted in late May. “You find the perfect worktop.” The video depicts her prancing around in a blouse that has elements of a classic men’s shirt with a completely reimagined silhouette. A series of pleats at the waist creates an exaggerated hourglass shape and causes the fabric to bubble over at the chest and peplum at the hip.

Wu first purchased the Exquise Tobie Top (which launched exclusively at Anthropologie in February of 2024) because she saw another TikTok creator posting about how flattering it was, noting that it “accentuates one’s waist while drawing less attention to the arms.” Now, she often wears it to work at her corporate finance job in New York City, but also in more casual environments. “I like it because I find it flattering for my body type,” she explains.

Wu is one of many young women publicly declaring their love for the Tobie silhouette, which now comes in 15 forms of blouses, mini and midi dresses, and jumpsuits across 30 colours and patterns, extending from petite to plus sizes, and retailing from $138 for a top to $198 for a long dress. Its most distinctive characteristics are that waist-pleat detailing, an exaggerated sleeve, and puffed hip, which, in the context of the dresses, extends to a full skirt. With more than 100,000 searches on the retailer’s website, the Tobi has become so popular that Anthropologie has had to restock its most popular style 20 times.

It’s also been rented tens of thousands of times on the resale site Nuuly. According to Sky Pollard, head of product at Nuuly, “The younger customer (under 30) is using it to dress ‘office appropriate’—perhaps this is their first summer working in an office—while the older customer (over 30) appreciates the flattering waist definition and versatility of this shirt-dress-inspired style.” Despite its recent tumble into the zeitgeist, the design is not technically new but many, many decades old.

The Tobie hearkens back to the styles that American ready-to-wear designer Claire McCardell created nearly a century ago. “She loved the practical beauty of a men’s shirt,” says Elizabeth Evitts Dickinson, author of Claire McCardell: The Designer Who Set Women Free. Iterating on its traditional shape, “she did a great deal with shirtwaist and shirt dresses,” and she used constructional elements like pleats to serve as both functional and beautiful details, in a manner very similar to the Tobie.

“I own this dress,” Dickinson prefaces. “I bought it because it was reminiscent of a McCardell.” She goes on to outline its McCardellisms, or the idiosyncratic design elements over which McCardell felt some sort of ownership after bringing them to the masses. They include the pintuck pleating to create an exaggerated waist without corsetry or boning, the front-button closure for easy access—no hard-to-reach zippers—ballooned sleeves for full range of movement, and the hidden side-seam pockets.

McCardell was known for her innovation in design, granting women freedom by transferring the conveniences of menswear to women, without sacrificing style. “The thing I’ve noticed about the Tobie is you’re seeing it do exactly what McCardell espoused, taking you from day to night,” she says. These were clothes that served women in every scenario of their life, whether they were at the office, a cocktail party, or in the midst of raising children. “Independent clothes for independent working gals,” as McCardell said, were monumental in the ’30s and ’40s, as women were heading to the office in droves, often for the first time.

But is that same shape revolutionary nearly 100 years later? “We are still trying to figure out what women are allowed to wear to signal being a professional,” posits Dickinson of the precarious tipping point between masculinity and femininity as it pertains to corporate dress. “Women have never really left that place of questioning what it means to get dressed to go to work every day.”

Nowhere is that better evidenced than last year’s explosive “corpcore” microtrend that fetishised corporate tropes with its cropped blazers, exaggerated pencil skirts, and severe heels. Brands like Aritzia and Zara, even Shein, then capitalised on the trend, marketing it to Gen Z as it entered the office for the first time, hoping to dress the part. Ironically, this look subsequently became more of a going-out ensemble than a going-to-the-office uniform; it wasn’t functional enough.

The Tobie’s softer details stand in opposition to this tropey rigidity and, at first glance, might align more with another sweeping trend du jour: the tradwife aesthetic. Its shape does allude, in a more general sense, to one favoured by housewives of the ’50s, an irony that’s all too poignant at the moment. (Tradwife is short for “traditional wife” and encompasses a movement of women embracing more traditional domestic gender roles characteristic of the 1950s.) “Right now in America, we have a very strong, regressive political message coming from Washington,” says Dickinson. “It’s happening in our laws. It’s happening in very explicit remarks made by men in power that women should go back to being housewives,” says Dickinson, admitting, “If you saw this dress on a tradwife making a soufflé, you wouldn’t blink an eye.” But it would be unfair to leave the conversation there.

“The shirt or house dress is a very complicated silhouette because it signals a woman’s role in the world as being a homemaker more than anything else,” Dickinson admits. That sort of ’50s silhouette has come back into fashion, whether it’s the Old Hollywood look proliferating on the red carpet or Jonathan Anderson dressing Sabrina Carpenter in Christian Dior’s famous New Look, which originally debuted in 1947. But McCardell’s version and Anthropologie’s subsequent riff on her time-tested concoction of function, comfort, and style alludes more to the work of modern womenswear designers like Tory Burch, who dedicated an entire collection to McCardell in 2022, with this silhouette featuring heavily, than a literal 1950s house dress.

As a case study of a more contemporary customer, Wu says, “I love that the Tobie strikes a balance between femininity and structure. Compared to the sharp tailoring of ‘corpcore’ or the office-siren look, the Tobie feels softer and more approachable—without losing that polished, professional feel. On the other hand, it’s more refined and waist-defining than the looser, romantic shapes of the tradwife aesthetic. I like that it makes me feel put-together without trying too hard.”

This simple, flattering Anthropologie dress sits at the middle of this minefield of a Venn diagram of regression, femininity, and freedom, but it seems to occupy its space with confidence. Zoom out and the Tobie silhouette is “this interesting mix of femininity meets office casual, which is unfortunately so revealing when it comes to women’s desires for workwear today,” says Dickinson. In the end, most of us are still just looking for comfort, style, and pockets—and that much has changed very little in the past century.

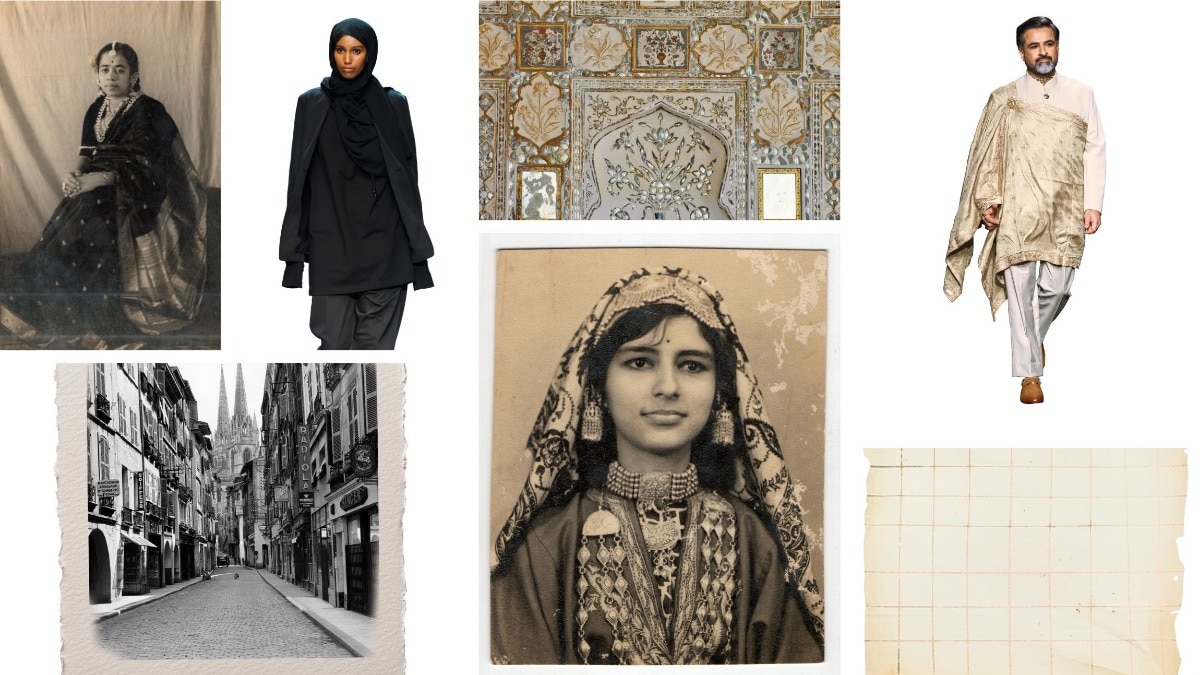

Lead image: Courtesy of Anthropologie

This article originally appeared on Harper'sBazaar.com

Also read: Is fashion becoming more sincere?

Also read: How to try the sardine girl summer trend without going overboard