This exhibition traces the Parsi gara’s passage across oceans, trade, and time

Ashdeen Lilaowala and Bhasha Chakrabarti’s recent exhibition at Rhode Island School of Design traces the Parsi gara’s journey across oceans, trade routes, and generations.

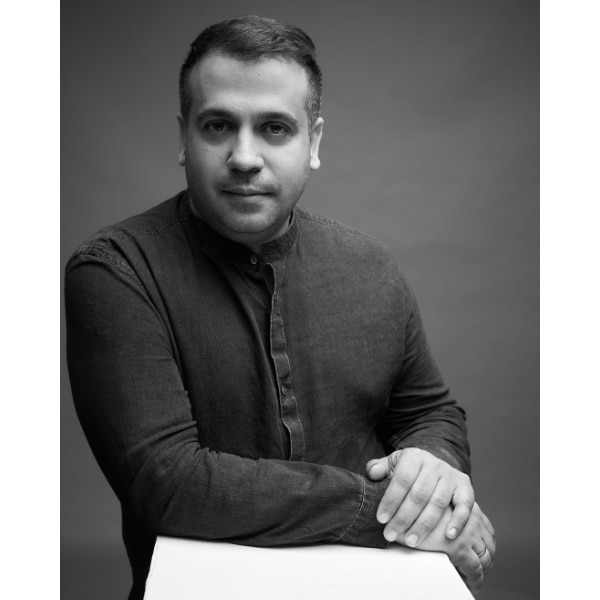

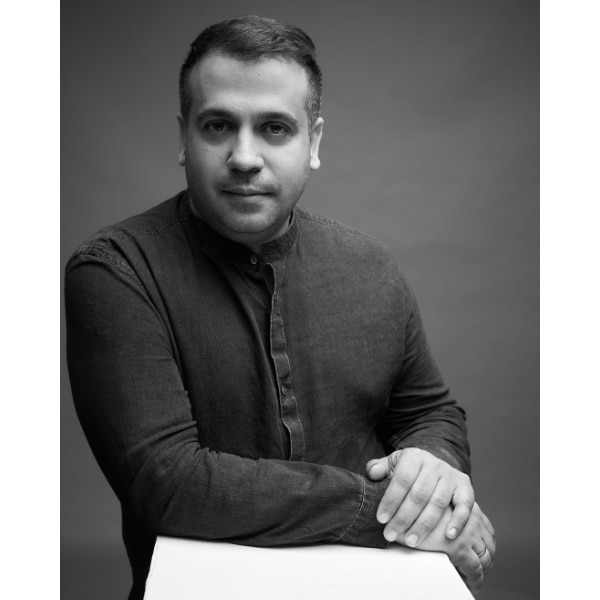

I see Ashdeen Lilaowala for the first time through my laptop screen, a modern-day artist in his Mumbai house, dressed in a sakura-pink shirt, his hair neatly brushed back, and his smile ample. Yet, when he speaks there is a nostalgia-laced, almost otherworldly quality to him that is irresistibly beautiful. His earliest memory of the Parsi gara embroidery, he shares, is not anchored in a museum vitrine or a scholarly text, but in the intimacy of family life. Lilaowala recalls the poignant image of his mother wearing a black heirloom sari scattered with pale yellow roses—an image so vivid that even today he wonders whether it is memory or photograph that has fixed itself so clearly in his mind. In many ways for me, this ambiguity mirrors the nature of the gara itself, which over the course of our conversation I come to view as an intertwined triptych of personal recollection, community folklore, and global history.

For generations of Parsis, the gara has functioned as more than ceremonial attire. It is a vessel of inheritance, a repository of stories that carries within itself the knowledge of who wore it and on what occasion, while also remembering to look to the future and asking which daughter or granddaughter it will pass to next. Lilaowala grew up surrounded by these conversations, absorbing not only the visual language of the embroidery but also the myths, anecdotes, and half-documented histories layered onto it over time.

Trained as a textile designer at the National Institute of Design, Lilaowala initially approached gara not as a designer but as a researcher. Early in his career, he travelled across China and Iran, mapping the historic routes through which Parsi traders carried Indian cotton and opium eastward, returning with tea, porcelain, and—perhaps most significantly—the embroidery techniques that would evolve into the gara. At the time, this research had no commercial intention. But a friend’s innocent ask changed everything for the young designer overnight. By 2012, Lilaowala had launched his label, with a clear vision of working exclusively with the Parsi gara for the modern woman. “I never wanted to slavishly copy traditional pieces,” he says. “I wanted to make the gara fun and contemporary for a younger audience because at that time there weren’t many people in Mumbai who were working with the embroidery. There were a few stray pop-ups and some female-led businesses, but no actual awareness.”

When Lilaowala entered the fashion landscape, gara existed largely within domestic spaces or small, informal ateliers. His vision was to position it as a contemporary design language and drawing on his formal training, he began dismantling the visual assumptions around the technique. Heavy, densely embroidered borders soon disappeared, while motifs began to get scaled up and scattered freely across the fabric. Cranes, borrowed from East Asian visual vocabularies, floated across saris like memories untethered to time. Thirteen years on, that practice has now moved into experimentations and collaborations with other brands like Ekaya Banaras for Banarasi silks, and Kanakavalli for kanjeevarams without diluting the embroidery’s core identity.

It is this sensitivity to history and reinvention that found itself profoundly expressed in his recent collaboration with artist Bhasha Chakrabarti for an exhibition titled The Flower, The Labour And The Sea, at Rhode Island School of Design. Chakrabarti, whose work often interrogates memory, trade, and material culture, approached Lilaowala while researching the opium trade: an intoxicating and ethically complex force that paradoxically gave rise to one of India’s most exquisite embroideries. “There are dual signifiers in the title,” explains Chakrabarti. “The ‘Flower’ refers to the poppy, which was central to the opium trade, and also to the floral motifs which characterise the gara embroidery. ‘Labour’ refers to the labour extraction that took place in Indian opium plantations as well the labour-intensive process of making the gara, and finally the ‘Sea’ which is the route through which the opium and gara cross lands.”

Together, they conceived a monumental embroidered sari in raw silk that functions almost like a cartographic narrative. India and China sit at opposite ends of the textile, connected by an Old Purple ocean alive with ships, mythical sea creatures, dragons, and urchins. Opium factories, ports, and maritime routes unfold across stitches, blending documented history with imaginative fantasy. The collaboration unfolded fluidly over nearly two years, one that Chakrabarti fondly calls one of the “most intimate artistic collaborations” of her life. For Lilaowala, the ease of cross-continental communication through text messages and video conferences offered a poignant contrast to the perilous journeys undertaken by Parsi traders centuries ago. “There is something very poetic about how the gara was made in one country, and it literally crossed the sea several times before it could finally be exhibited,” adds Chakrabarti. “Working on this project felt like some reparative justice for the kind of trauma associated with the gara’s history.”

The exhibit is also accompanied by a short film of Chakrabarti pleating and draping the sari on herself. This crucial collage of moving images immediately elevates the gara at the heart of this exhibition beyond a static artefact, and forces viewers to confront it as a living piece of art. “I work with textiles as objects that are meant to be lived in, and I knew the moment the sari entered the space of the museum it would never be worn again. It is a painful thought,” explains Chakrabarti. “So I decided to wear it once, to honour its beauty. But eventually I decided to record it because the way the sari wraps and unwraps itself on the body is beautifully in sync with the trade routes embroidered on it.” If the sculptural opulence of the sari is blinding, Chakrabarti’s film adds a much-needed touch of humanity to the project. In this film, the sari’s measured drapes and folds only further underscore the six yard fabric’s vast quotidian and ceremonial history. “Much of my work is about textiles in relation to the human body. Just because something is in the sterility of a museum space, doesn’t mean it is not meant to be close to the body and being close to the body doesn’t lessen its artistic merit.”

As global attention turns increasingly towards Indian craft, Lilaowala remains measured in his expectations for gara’s future. He sees it as inherently niche, defined by time, labour, and cost. “It will have moments in the spotlight,” he says, “but it will never be mainstream.” In his Mumbai store, however, young brides continue to commission garas for weddings. Many of them arrive informed by snippets of history shared through the brand’s social media, with a deep-seated urge to make the historical fabric their own. Increasingly, Lilaowala notes, the saris he creates for bridal trousseaus carry deeply personal motifs: a Lego brick hidden among flowers to honour a lost parent, a line of Rumi embroidered where only the wearer will ever see it. “Some things are meant only for the woman wearing the sari,” Lilaowala says with a smile.

Lead image: Team Ashdeen & Bhasha Chakrabarti

Inside images: Nishant Sharma, Team Ashdeen & Bhasha Chakrabarti

This article first appeared in Bazaar India's January 2026 print edition.

Also read: Valentino Garavani, the man who showed the world the power of red

Also read: The fashion era that was 2016, explained