How this designer is challenging glamour-led fashion with craft-first design

Designer Rina Singh straddles rationale and intention to navigate the complexities of time-honoured craft and textile traditions.

"I hope I am not boring you with an onslaught of information?” Rina Singh pauses as she sifts through 15-odd blocks of all shapes and sizes used in a single block-printed floral motif on a piece of handwoven textile, and asks me. Her reverence for craft and her ‘people’ is beyond obvious as her eyes gleam like a child proud of her treasured toys. How could I, or any other fashion writer, be bored in an interview where you have to hardly look at the prepared questions to tick off the topics of discussion? The brilliant mind behind the textile-led design studio Ekà, Singh, is fresh off the launch of her third retail space in Gurugram, where she unveiled her much-lauded Autumn/ Winter’25 collection, Chamba. Early on in the conversation that started at her store and progressed to her studio, she tells me, “Two languages have established fashion at large—first is couture and the second is glamour. When it is neither, then it takes a while for people to take you seriously, especially when it’s not a basic clothing line.”

It is in this very category that the designer has carved a niche over the last 13 years, resorting to extensive research and experimentation with textiles and the dextrous craft legacy of our country, and still finds a gap in people putting money where their mouths are. “I don’t think I would have been able to do what I’m doing today if I were not selling more globally than I am. I shouldn’t be apologetic about saying it, because it is the truth. You have to reduce, remove, and extensively ‘decorate’. We have a niche and a small audience for Ekà. It doesn’t always give you the return that you want. But if I weren’t doing what I’m doing internationally, I don’t think I would have been able to afford what I do in India today to establish my label and find a way to say ‘this is who I am’.” The label’s contemporary take on Indian craft traditions vouches for the prominent appeal across Europe, Asia, the UK, and the US. Needless to say, the new store echoes the brand’s ethos, rooted in a sense of familiarity, timelessness, and the expression of life itself. Handmade tile roofs, wooden details, earthy tones, antique furniture from Sri Lanka and Kochi, and cast human forms replace traditional mannequins, collectively evoking an old-world charm, as if in a symbiotic relationship with Ekà’s clothing. The studio is a derivative of the same ecosystem—one that is planned around circularity for a team that shares the same passion as the designer.

Singh’s design vocabulary charts new directions for time-honoured craft techniques, from handweaving to block printing, embroidery to embellishments. The Autumn/ Winter’25 collection is inspired from the traditional Chamba Rumal embroidery known for its do rukha taka (double-sided stitching) that makes the fabric appear identical on both sides. The technique is imagined through weaves, embroideries, and layered applications on organza, silk, taffeta, wool, and linen. “I will not make a plain black sweater and sell it. I don’t come from that place. When I design, I create with everything that surrounds me—from a window in a house to a flower in the corner, or an animal crossing the road—this is literally my mood board. All of it finds expression in my designs. The design vocabulary is rooted in India, while I interpret it in my own ways.” You will never find a single Indian textile as it is in Singh’s world—a jamdani sari will not be turned into a dress here. There will be jamdani oral motifs on a linen dress, Chamba Rumal embroidery on a shirt, or jacquard zari motif on a wool coat. “This is the crossover that I want people to experience as I transport them into a familiar, yet whimsical, world where they feel like something shifted here but can’t put a finger on it. That’s what I do with the clothes—from the shapes, textiles, bodies, to the Indianness of design and what I intend to carry forward as the legacy of our craft.” While Indian textiles take precedence here, the prints and surface embellishments appear lived-in rather than brand new. Billowing silhouettes are intelligently engineered with pleats, tucks, and gathers. No surprises; Issey Miyake’s play of proportions deeply inspires her.

While logic infers the designer’s affinity to the anti-fit silhouette to mindful size inclusivity, Singh has a deeper rationale for it. “Historically, we were not a fashion-informed country. We were not stitching our clothes. We were only working on yarns for drapes like dhoti and sari. With Islamic rule came the stitched concept of choga made with zero wastage. Everything was handwoven and super dexterous; man-hours were expensive even then. So there was no concept of waste. It is just a 100 per cent intelligent and ergonomically designed model. Suppose I’m working with such old traditions, for me, making a blazer out of any textile is not possible. In the end, the whole concept of trying to achieve a larger shape or gather is to be mindful of the delicate textiles and also reduce waste.” The designer learns from every success, every failure, and every order about what works and what doesn’t. “Fashion is so dynamic. You have to have your ear to the ground. Therein lies my real growth, I feel,” she reflects.

These time-honoured traditions are the building blocks of the fashion ecosystem, and Singh strives to occupy a place of pride with her distinctive aesthetic, intentionality, and mindfulness. Inspired by poetry, art, and nature, she has successfully created a whimsical world where clothing is envisioned as an armour for the wearer, but also as their cocoon. “You make it [clothes/designs] cool, you make it beautiful, you have people’s attention, and you make them invest in it. Once they’ve invested, they are a co-partner in the story, and then you talk to them,” Singh emphasises the importance of cultural context and storytelling in fashion.

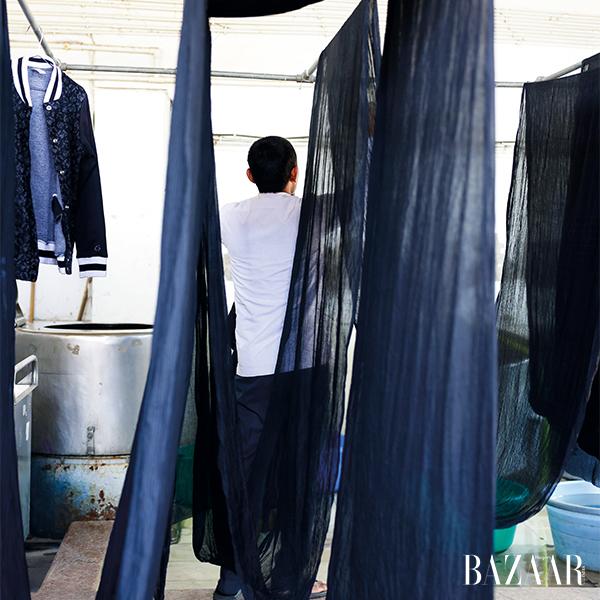

Fashion and sustainability are often misconstrued, and the designer calls out the marketing gimmicks prevalent in the industry. “But how do I make the brand philosophy eco-conscious? By working with crafts and supporting the artisans over the years. I design consciously. My design language is craft-informed.” She points out the printed stripes gathered on the border of a dress that took eight-10 blocks to achieve the desired pattern. “I can very happily achieve this on a machine. But I print it with the block. I go back to the artisans. For me, to have this conversation with somebody, the other person has to be equally invested. I know what I’m doing. I really don’t have to scream it from anywhere. People who show an interest in the beauty of Ekà come back to buy it, and then we open their eyes and educate them about our craft.” She works with craft clusters across Bengal, Rajasthan, Bihar, Gujarat, Himachal, and Telangana. The final product is a culmination of research of traditional craft wisdom, and technical prowess brought to the fore together with her in-studio team and artisans across the country.

The empty chatter around empowering artisans in the larger narrative of modern Indian fashion concerns Singh. “They don’t need saving. They don’t need your sympathy. They know when a designer is involved, their work is going forward. Otherwise, people generally bargain with craftspeople in local haats. When it’s a designer product, working with the same artisan makes the item aspirational and the association collaborative.” It’s a very complex chain because, at the end of the day, if they are not getting paid, it’s not a sustainable model. “They don’t care about walking on the ramps alongside models or being photographed for brand campaigns. They care about the money that comes to the bank. It boils down to the colour TV they can buy, the car they can afford, the pakka houses they can make, their children going to medical schools, etc. The economy of everything comes first and their skills, the artisans are not insecure. The sooner we get rid of this whitewashing, the better it is for us.”

The fashion industry has more to offer than what we think it does, feels Singh. There is a dire need of a collective voice in India and a robust business model. “We have to rethink and re-evaluate our standpoint. We can’t resort to the same outdated concept of entertainment in fashion. It [the industry] has to reconsider everything if Indian fashion wants a place in the world.” We have barely scratched the surface internationally. “Each one of us is fighting our own battle in a silo. Somebody achieves something, and it’s just one speck in the larger picture. We will never have a fashion house until India establishes itself, takes onus in creating a strong identity of what we want to go for,” she signs off.

Images: Tongpangnuba Longchari

This article first appeared in the December 2025 print issue of Harper's Bazaar India

Also read: What are fashion's future classics?

Also read: Does India need Prada to sell its Kolhapuris, or is this just fashion déjà vu in new shoes?