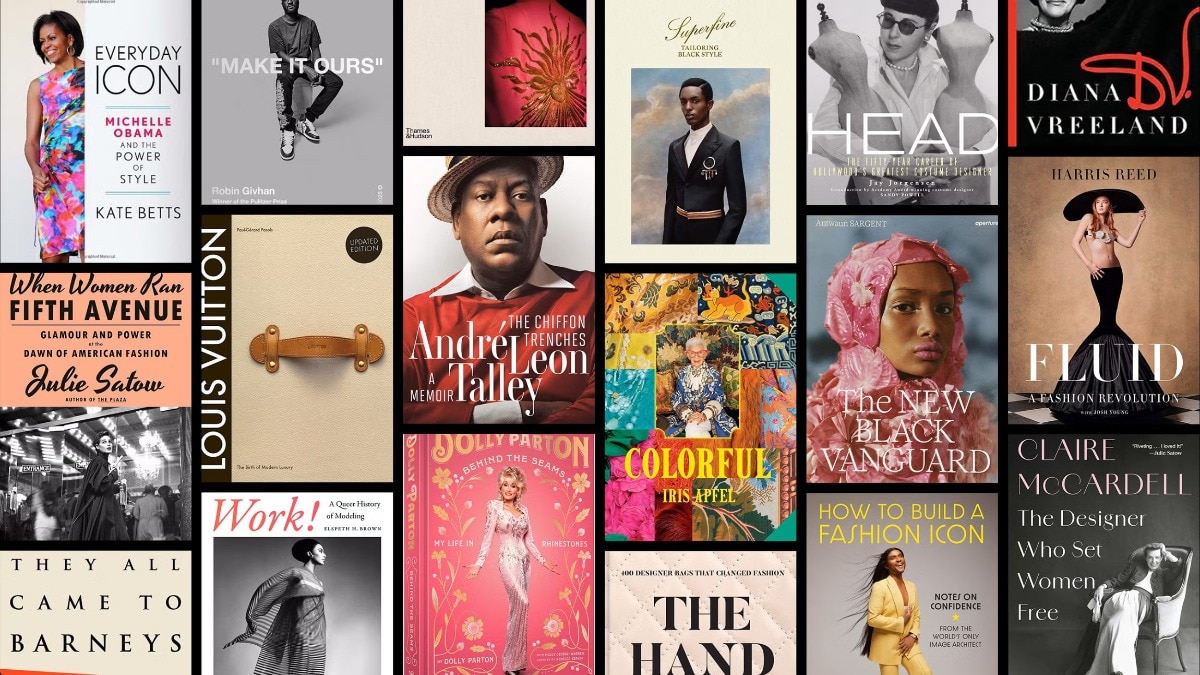

Muzaffar Ali traces the journey of iconic women who have adorned the silver screen

The Indian filmmaker and fashion designer relives the golden era.

As far as I can recall, the best stories are narrated by women. As children, one remembers a wrinkled face keeping us spellbound by means of stories till we fell asleep almost every night. Women have stories written on their faces. They carry their own pain and also, the pain of others. The classic novel, Umrao Jaan, by the poet, Mirza Hadi Ruswa, begins with “what is more enjoyable, the story of my life, the life I have lived, or the world I live in. Or the story of the world”. An actor lives these stories…creating characters into legends, and, in the process, becoming legends themselves. They are the muses for writers and composers and, of course, directors.

I have always been inspired by women as carriers of culture, symbols of emotions and milestones of empathy.

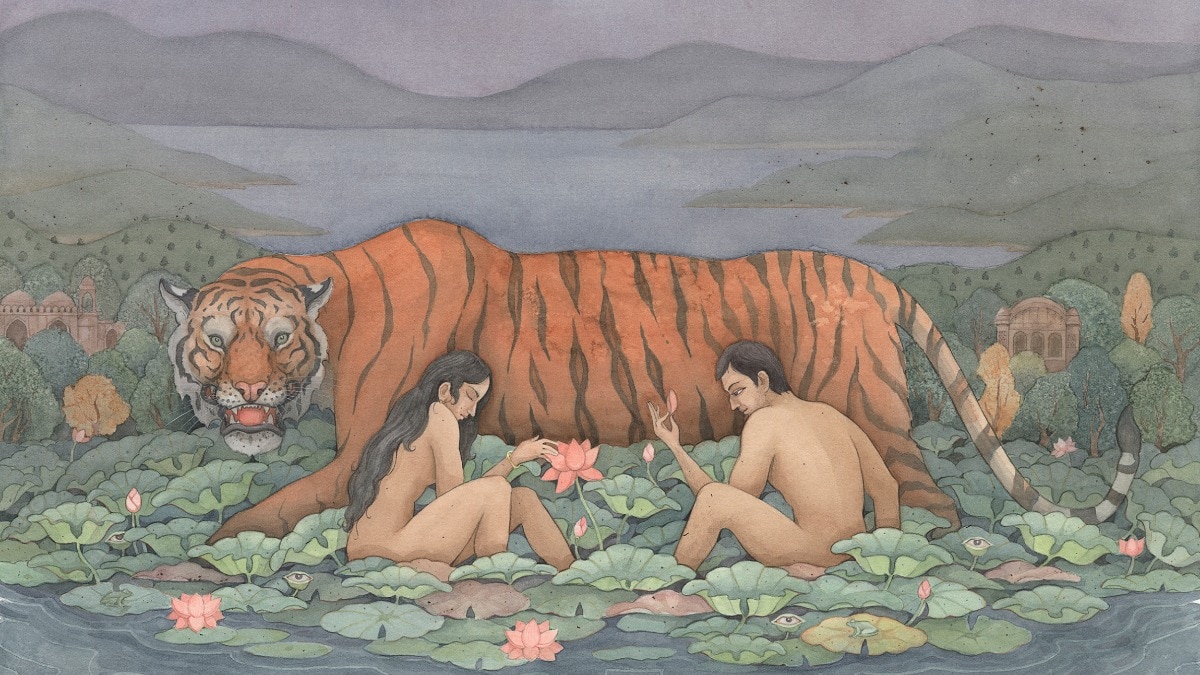

India has grown up with faces that are symbolic of history, legends, and icons of sensuality and feelings. They exude a poetic chemistry and, with their co-stars, conjure up an everlasting poetic grammar. So, to paint this canvas of beautiful faces that have adorned the silver screen, I have to explore the treasure house of my nostalgia and delve into the vocabulary of my work. Each has its own magical journey.

My first tryst with this adventure of faces and stories was with Smita Patil in Gaman (1978). She was beyond stories…a story of silence. She was a symbol of a predicament and a metaphor for yearning that she shared with millions of women left behind in villages waiting for their husbands’ return. This became larger than life, as it expanded into a lifelong saga of wait. I was thinking of characters from Satyajit Ray’s films…so down-to-earth that they bore the fragrance of the soil. The sparse use of language made his work sheer music. Thus, Bengal came to the shores of Bombay with its deep sense of romance, storytelling, and music. They created characters that became memorable crafted with music. Songs that brought them into a realm of the heart where they will dwell forever, closely guarded by emotions and imagination. It resulted in opening a new world of romantic realism with a lining of socialism and secularism to touch the masses.

Waheeda Rehman danced her way into this world in films such as Guide (1965), where Rosie overshadowed the main protagonist, Raju, or in Pyaasa (1957) where she plays a poet’s muse. Verses penned by larger-than-life poets became larger than life themselves. Nargis became the epitome of a mother of the nation in Mother India (1957). As a romantic muse in Shree 420 (1955) and Awaara (1951), she was no less than her mentor and co-star Raj Kapoor. And even more in Andaz (1971) with the passionate Dilip Kumar.

There was a huge creative industry including singers and melody makers behind these heroines conjuring words that would make each song sway. Create a dream world around them that would immortalise their aura. Even the song of their male counterparts who would glorify their beauty like never before and never again—be it Chaudhvin Ka Chaand Ho Ya Aaftab Ho, Hum Bekhudi Mein Tun Ko Pukare Chale Gaye, or Abhi Na Jao Chhod Kar. The man-woman chemistry electrified this powerful magic on screen.

Madhubala was a phenomenon that shook the Indian screen with her endearing and infectious, giggly charm. It took her to varying, dizzy heights. An Indian (Marilyn) Monroe of epic proportions that shook the country as Anarkali in Mughal-E-Azam (1960) with another passionate rendering of Salim by Dilip Kumar. Each song touched the heart and ripped the soul. The magic of this blend of talent placed the Indian woman on a pedestal in a way the world had never seen before. Some of these projects may have lacked in production design but abounded in cultural and emotional content. The dance form of Kathak also found new metaphors in expressions and body language.

Masterful portrayals, one following another, were etched on the tablet of these romantic dreamers. It seemed poetry was created for these immortal characters, with actors such as Nutan in Bandini (1963) and Sujata (1959), Meena Kumari in Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam (1962), and Waheeda Rehman in Chaudhvin Ka Chand (1960). Each of these characters were fused with cultures and times.

Slowly, as the screen power grew, its cultural and creative ecosystems became weak. Stalwarts—especially the ones who came from an evolved culture such as Suchitra Sen—withdrew from Bollywood to Calcutta after intense portrayals in films such as Bombai ka Babu (1960) and Aandhi (1975). She also immortalised songs including the popular Chal Ri Sajni Ab Kya Soche (Bombai ka Babu). I watched these icons on screen as a child, and their performances wrapped in layers of talent made an unforgettable impression on my mind.

There were three strains of cultures all trying to embrace each other with the sole purpose of creating one monolith product for one market. Bengal, Punjab, Awadh…all engulfed in the beauty of Urdu, which made the woman protagonist extremely romantic and endearing. The queen of this ethos was none other than Meena Kumari who immersed audiences in Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam (1961) and Pakeezah (1972).

Maharashtra was abreast of this exquisite feminine world of camera talent with Nutan, Tanuja, their mother Shobhna Samarth, and, of course, Durga Khote. Nutan as star could present one outstanding story after another…think Bandini and Sujata by Bimal Roy.

South was not far behind with the dynamic versatility of Vyjayanthimala in Gunga Jumna (1961) and Madhumati (1958) with no less than Dilip Kumar by her side. Sridevi who could outdo any diva, as could Hema Malini. Poems and poetry continued to celebrate their deep sense of romance, which through Urdu had become a national language. The ‘Aye-Dil-E-Nadan’ wandered in and out of palaces, rode horses, and traversed the desert on camels.

It was also from the South that Rekha appeared…she was also the one I discovered for my poetic dream, Umrao Jaan (1981). For me, creating a story through the eyes became a way of seeing the world and showing it in the drama of time and its seasons. My film, Zooni (unreleased), being shot in the four seasons of the Kashmir valley with Dimple Kapadia as Habba Khatoon, the context of this you may find in my autobiography, Zikr—in the Light and Shade of Time. I talk of design and culture in crafting characters and the powerful organic relevance of art. Today is the new age of over-the-top extravaganza and unreal opulence. Design and content have taken new routes (I wouldn’t say it’s taken a back seat).

Unfortunately, Bombay (now Mumbai) missed a few steps in the global photographic era—especially where a shutterbug such as George Hurrell could freeze German-American actress, Marlene Dietrich into a paragon of beauty. Having worked in Bombay with Air India in the ’70s, there were no such masters of the frozen image who could have made art out of portraits. The few I recall were Mitter Bedi and his iconic image of novelist, Shobha De, Jehangir Gazdar for legendary Colleen Bhiladwala, followed by Gautam Rajadhyaksha and Prabuddha Dasgupta. Today, a number of brands have taken over the digital world and stars now have too many endorsements to make at the cost of losing the story. People, too, are lost in looking for what they can buy rather than what they can feel. The extravaganza surrounding them, and the jewellery-bedecked costumes take away the meaning of their tales. However, I cannot end without a salute to the beauties of today such as Kareena Kapoor and Alia Bhatt and the legends they can create. The future waits with bated breath for the stories on the faces of tomorrow.