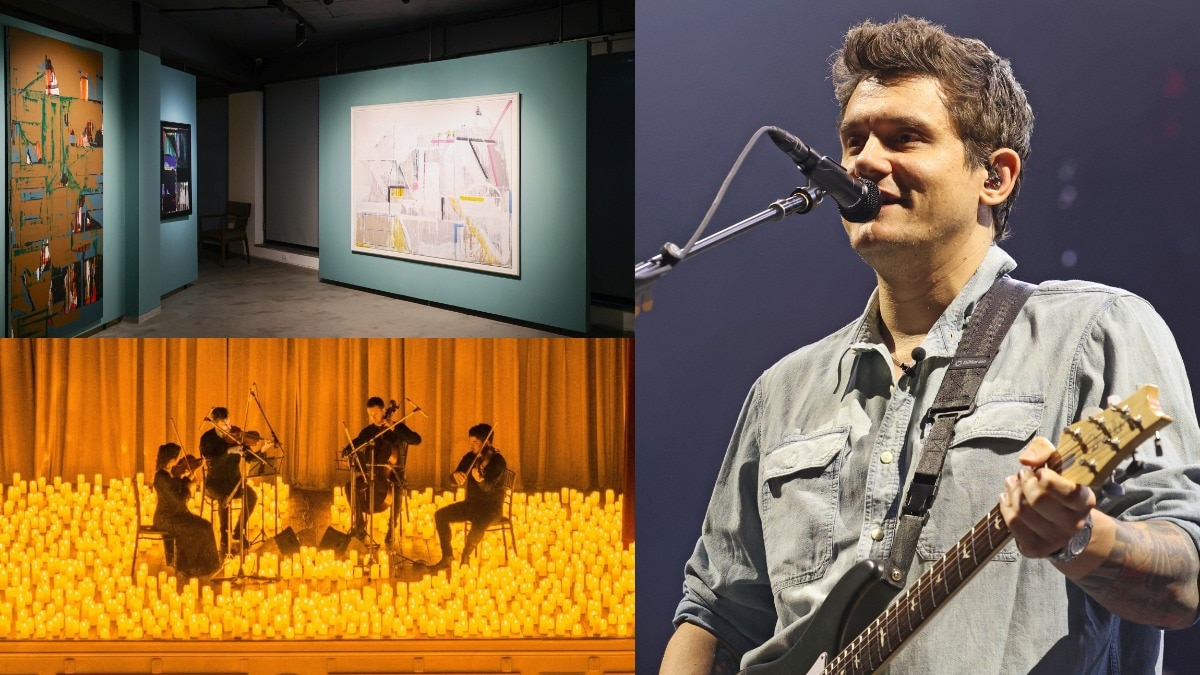

Guardians of expression: India’s pre-independence art galleries and their lasting legacies

From cultural salons to national treasures, these historic art institutions have shaped the narrative of Indian creativity—preserving the past, influencing the present, and redefining the future of artistic expression.

In 1904, in Bombay, Sir Pherozeshah Mehta moots the idea to create a cultural centre. The presidency approves the proposal with one caveat:The public needs to sustain it. On January 10, 1922, the Prince of Wales Museum opens its doors. It is now known as the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (CSMVS), which is run by the people, for the people, and shares its stories with the people.

It is 1936, one Ram Chand Jain, fondly known as Ram Babu, opens a stationery shop—Dhoomimal Dharamdas Stationers and Military Printers—in Connaught Place in Delhi. By 1949, the shop’s first floor is a hub for artists like BC Sanyal and Dhanraj Bhagat, who have established the Delhi Silpi Chakra. When the group relocates in 1957, the space evolves into what is today known as Dhoomimal Gallery.

In Kolkata, Lady Ranu Mukherjee (in picture) rents a room in the Indian Museum in 1933 to host an art exhibition under the newly formed Indian Academy of Fine Arts. By 1960, the society transformes into the Academy of Fine Arts, with its own institution. Starting with 50 works by Nandalal Bose, the Academy has nurtured a legacy that continues to shape the art landscape.

A palpable sense of movement swept across pre- Independent India, a nation on the cusp of freedom. Amid political upheaval and cultural resurgence, this movement—for expression, rebellion, and liberty—found a voice in art. Art became not only a bridge between a subjugated people and their vision of a nascent nation but also a catalyst for its liberation. Three cultural addas emerged as the humble cradles of this expression.Today, these addas stand as India’s most revered galleries, transcending time to preserve the essence of humanity. These galleries are more than repositories of art; they are custodians of India’s collective consciousness. Their founders, perhaps unaware of the magnitude of their contributions, gifted India the institutions that serve as centresofdiscourse,reflection,andinspiration. With77 years of independence behind us, these galleries continue to evolve while retaining their place in the social, political, and economic narratives of the nation.

GALLERIES THEN AND NOW

Indian galleries have long mastered the delicate balance between preserving classics and showcasing modern works. This dual approach, rooted in collaboration, was born from the camaraderie of close-knit artistic communities. As Uday Jain, the third-generation steward of Dhoomimal Gallery, aptly puts it, “It was an everyday thing where artists would get together and have conversations, sometimes even arguments. And from those discussions, exhibitions would come out.” He recounts how the gallery identified talents like Vivan Sundaram and Bikash Bhattacharjee through these informal interactions. “With such great connections to artists, the best of Indian art automatically found its way to the gallery,” Jain tells Bazaar India.

DEMOCRATISATION OF ART

A cultural institute should transcend generations, believes Sabyasachi Mukherjee, director of CSMVS. For CSMVS, democratisation manifests through its governance and initiatives.“We are temporary custodians of public property, not owners. Accountability and ownership are instilled from day one,” Mukherjee adds. The initiatives tell their own story. Museum on Wheels brings art to a wider audience, attesting to its existence and relevance even far away from the curated spotlight while the Children’s Museum empowers kids to curate their own ideas, breaking down elitist notions of art. “We built a separate creative space for children, away from any imposition of adults, where the kids are allowed to study collections, select pieces, and prepare their own narratives,” explains Mukherjee. Meanwhile, Dhoomimal propagates a simpler philosophy, aimed at altering the common perceptions of art. “Invite schools—start at that level of just viewing. Open up the minds of the children to the reality of art and take up the discourse on not everything being just a pretty picture. Let them find it horrifying,” says Jain. Recalling his own upbringing surrounded by artworks, he explains how drawing parallels between the shape of a balloon and a Swaminathan painting was just his way of articulation. After all, art doesn’t always need interpretation; it just needs to resonate. With art’s elitist veneer still dominating, both the institutions reinstate the role of art galleries in dismantling its reputation as a commodity owned by the exclusive niche. “The only coverage that art gets in news is prices and fake,” Jain asserts. “That’s just a very small part of the art ecosystem, shutting out the majority of the people. Galleries have to make art more human.”

SUSTAINING HERITAGE

Institutions like the Academy of Fine Arts, which once stood as the cultural epicentre of the state, is now strained by a lack of funds. Surviving precariously, they rely on modest streams of income. “We sustain ourselves by renting out seven-day exhibition slots each month across our six galleries, and these earnings are used to cover staff salaries. Some of our funding comes from commercial shows, often sponsored, which help support a handful of activities,” says Kallol Bose, the Academy’s Joint Secretary. With an entry fee of just ₹25, the Academy is sustaining through pleas for monetary assistance while continuing to preserve works by icons like Hussain and Tagore.

TECHNOLOGY AND EVOLUTION

The narrative regarding integration of technology has always oscillated between extremes. While we have a disposition to generalise it as a boon or bane, Jain believes technology and tradition can co-exist. Referencing, The Life of a Kettle by Ranbir Kaleka, he speaks in reverence of the senior artist for setting a precedent of experimenting with medium. “As long as the artist still uses the same concepts and feels involved in the subject, it shouldn’t matter whether he uses his hands or technology. We should be done with the labels,it’s a matter of maintaining your identity across mediums,” he adds. As artists evolve, so must galleries, embracing diverse mediums while staying true to their essence.

MAINTAINING RELEVANCE

Imagine watching a play at Triveni Kala Sangam in Delhi or taking a stroll at the Indian Habitat Center.These evoke a sense of leisure, a sentiment not often propelled when it comes to art galleries. It is because these public art spaces have made the consumer experience more immersive. “Cafes help. In India, we make our art very serious. So a lot of common people get intimidated that they won’t be welcome,” stresses Jain. Combining art with music, food, and technology could bridge this gap, making galleries more inviting.

LOOKING AHEAD

Beyond their role in goading, presenting art, the vision of these institutions translates into the legacies they create.Mirroring the society in its most raw and surreal form, they foster an abode where everyone can come and look at themselves. “Humanity endures as long as culture exists,” Mukherjee agrees. Despite the vicissitudes of revolution, these galleries have fostered hope.As the revered pioneers of art found a living room in the walls of these galleries, don’t we owe it to them to find our space in the art landscape too?

Images: Dhoomimal Gallery, Academy of Fine Arts, and Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sanghralaya

This piece originally appeared in the January-February 2025 print edition of Harper's Bazaar India

Also read: We have entered the age of fauxductivity: Being busy isn’t enough anymore

Also read: Kiran Nadar on influencing and preserving the art of tomorrow