How Olivier Rousteing transformed Balmain into a global juggernaut

Over the course of his tenure with the brand, the designer has turned his skeptics into believers.

On a typical grey winter day in Paris, when the persistent drizzle of rain dishevels even its chicest residents, the French fashion designer Olivier Rousteing arrives at the Balmain headquarters in impeccable form. Dressed in all black—a sharp blazer over a hoodie—and a pair of oversized sunglasses, he radiates the star power of someone who is perpetually photo-ready. Even at 10 a.m.

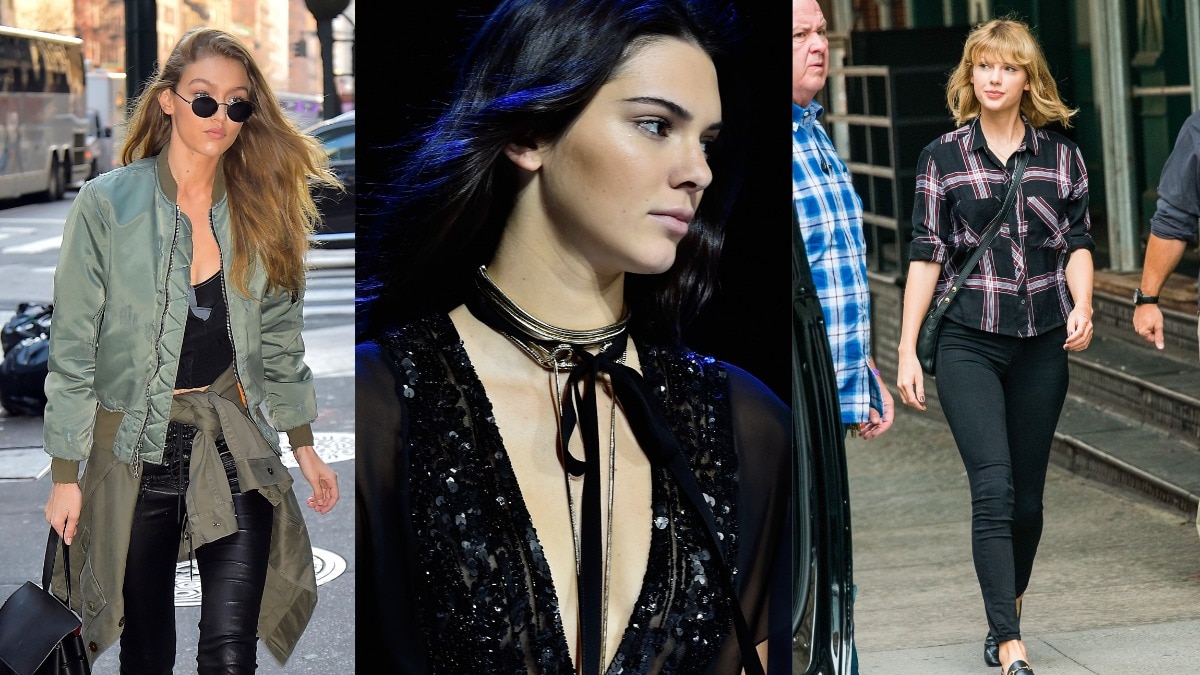

Since Rousteing assumed the creative director role at Balmain in 2011, his image has been a billboard for the brand. With 7.4 million followers on Instagram, he represents the modern-day celebrity our digital lives have shaped: the kind who seems glamorous and relatable at once. It’s a paradox he’s harnessed since he took on the job at the age of 25 when he became not only the youngest creative director in Paris since Yves Saint Laurent for Christian Dior but also one of the first Black designers to helm a luxury fashion house. Without subscribing to what is done or expected and often doing the opposite, Rousteing has, perhaps more than any other living designer, redefined what it means to be a luxury brand. Long before most, he embraced social media and influencers, elements once seen as in bad taste by his competitors. His vision of the Balmain woman was always inclusive and sometimes divisive, and he had foresight: He cast Rihanna in her first luxury fashion campaign in 2013 and, a year later, Kim Kardashian, alongside Kanye West, in theirs.

He has also expanded the brand’s reach by introducing menswear, relaunching couture, and moving beyond traditional fashion channels with music festivals, a streaming short-form drama series, and collaborations that span from Netflix to Barbie.

“I never tried to be a rebel or disruptive,” Rousteing says, sipping on his Starbucks and wheeling about on a chair behind his imposing L-shaped black marble desk. “Is social media luxury? Is it chic? Is it elegant? You don’t ask those questions when you’re young. When you’re young, you don’t care about the system; you want to create your own system.”

Last September, he rang in his 10-year anniversary at the house—a remarkable milestone in this fickle business in which creative directors have just a handful of seasons to prove themselves. It was an all-star fashion show for his Spring 2022 collection in front of a crowd of 6,000 guests at La Seine Musicale, a concert venue on the Île Seguin, an island on the Seine. Beyoncé recorded a message for a spoken-word soundtrack, Naomi Campbell opened the second part of the show—re-editions of the best from his oeuvre—and France’s former first lady Carla Bruni closed. It was also open to members of the public who had tickets as part of the two-day Balmain Festival, which featured headliners such as Doja Cat and Franz Ferdinand. Tickets to the show went for a small fee, and all proceeds went to (RED) and the Global Fund to fight the AIDS and Covid pandemics.

The event and collection were a joyful salute to freedom, a feeling we have all had a complicated relationship with of late—Rousteing, it turned out, especially. About a week after the show, he shared a photo of himself on Instagram that had been taken exactly one year before. It was not the usual flawless selfie but instead a picture of him wrapped in bandages with severe burns on his face. The caption revealed he had sustained the injury when the fireplace at his home exploded. Rescued by firefighters, he woke up in a hospital the next morning with second-degree burns on his face, arms, and chest. It took months to recover and for the scars to heal, but he concealed the event from all, covering up with turtlenecks, hoodies, and stacks of silver rings that encased his fingers, a touch of swagger he maintains today. “When you’re really falling apart and then trying to smile for every selfie … the performance was extreme that year,” he says. “I realized that social media is not reality but just who you pretend to be or what you want to show.” Still, he sketched his way out of misery, and the dressing and gauze wrapping he lived with inspired the final lineup of trailing bandage dresses in the Spring 2022 collection.

Rousteing arrived at Balmain, from Roberto Cavalli, in 2009 to work beside Christophe Decarnin, who was then the creative director. Decarnin was the force behind the original “Balmania,” credited with bringing the house (established by Pierre Balmain in 1945) back from the brink of bankruptcy and irrelevance. His brand of flamboyant brashness (some called it trashiness) was the uniform du jour for certain whippet-thin Parisians. His skintight shredded jeans, at more than $1,400 a pop, went flying off the shelves, and his military jackets with crystal frogging and fierce shoulders and second-skin minidresses garnered legendary waitlists.

When Rousteing, an unknown 25-year-old, took over in 2011, he continued to run with a more-is-more mentality, expressed through his formative lens of the ’80s, ’90s, and early aughts. Everything from the supermodels of his adolescence to the cinematic MTV-era Michael Jackson has shaped his definition of sexiness and showmanship. Riffing on his reference points, he amped up the skin-baring flashiness and added streetwear elements into the mix while also leaning into exceptionally detailed craftsmanship : embroideries, corsetry, intricate metal weaving, and quilted leatherwork that render many of his designs artisanal masterpieces. At a time when Phoebe Philo was reigning at Céline with her elegantly restrained, understated minimalism, his love of popular culture and his maximalist high-low mix engendered skepticism. (A 2016 New York Times article described his designs as “an acquired taste.”) As did his use of Instagram, which he embraced in his self-revealing, hand-on-his-heart way from day one. It’s laughable now to think of Instagram as a controversial tool, but discretion was once paramount to luxury in fashion. “Olivier became the Instagram Designer, which did not help him position himself as a serious designer at first,” recalls Balmain’s chief marketing officer, Txampi Diz, who has worked with the house since 2007.

“It was a really weird feeling when I was appointed,” says Rousteing. “I was really young, and sometimes there were frustrations in the office because of my age. I was afraid, too, I was young and unknown, and at that time there were only famous designers around, so I felt like it could be a bad start or it could become a revolution.”

What initially silenced the critics were the numbers—not just the millions of loyal followers on Instagram but the turnover, which has increased sevenfold in a decade. Rousteing’s ability to move merchandise has been great for business. In addition to expanding into new fashion categories, he has overseen the brand’s diversification with the launch of Wonderlabs, Balmain’s entertainment and innovation division. In January, he made a foray into the metaverse with NFTs. “Olivier always understood that the market didn’t need another fashion house,” says Diz. “He made it a global brand.”

That has not come without effort, and Rousteing says he has almost always had to put up a fight. “Some people are stuck in their traditions and you have to shake them a bit,” he says. His proudest achievement, by far, has been to instil inclusivity as a central tenet of the Balmain brand. Spearheaded by a squad of diverse and bold personalities, known as his Balmain Army (an intentional reference to battle), Rousteing’s shows, campaigns, and front rows have always represented the multicultural world that exists outside of the well-heeled arrondissements of Paris. “I keep pushing for it,” he says, “because now I think it’s beyond Balmain and [I want] for all of Paris to wake up and start being less exclusive.”

The week before we meet, the news that Virgil Abloh, the artistic director of Louis Vuitton menswear, had passed away from cancer at 41 floored the industry. “It’s so sad. It’s so shocking,” Rousteing says, visibly distraught. Abloh’s and Rousteing’s appointments were once heralded as progress. “There were two of us, and now I’m one.” (Abloh was the first Black artistic director at Vuitton.) “I realized it’s not because I am young that I do things differently. It’s because other people don’t like the new world we are living in,” Rousteing says of the persistent homogeneity, particularly in this rarified luxury world. He laughs, adding, “They just don’t see the world as it is.”

Born in France in 1985, Rousteing has always been something of an outsider. He spent the first months of his life in an orphanage before he was adopted by Lydiane Rousteing, an optician, and Bruno-Jean Rousteing, the manager of a marine port, both white. He had a happy childhood in the bourgeois southwest city of Bordeaux, but not knowing where he was from or who his birth parents were fostered a profound perfectionism, a need to prove his worth. He is a famous workaholic —his only downtime seems to be morning boxing practice—but is known as a delight to work with. “It is so rare to have such a hardworking person who never loses his sense of humour. No matter what happens, he never gets angry,” says stylist Charlotte Stockdale, who collaborates closely with the designer.

The 2019 documentary Wonder Boy sheds light on Rousteing’s struggles with identity. It follows the designer on his search to find his birth mother and entails heartbreaking revelations. In one of the scenes, he discovers that his mother was 14 when she got pregnant. He sees her handwriting—the looping letters of an adolescent and not of the maternal figure he had envisaged. He learns, too, that his father was much older, and he interprets this to mean that his conception was not consensual, a possibility that leaves Rousteing bereft and sobbing on camera. At the end of the film, he decides not to take his investigation any further. “We stopped because whatever comes next is going to be between my mother and me,” he says, though he adds that he feels she would have tried to track him down if she wanted to by now. Despite all his millions of followers and the close-knit creative team Rousteing works with every day, he cuts a solitary figure in the film. There are several wide-angle shots of dinner for one at the long table in his dimly lit kitchen. “I was thinking, Fucking hell, that guy is so lonely,” he says of when he watched the first edit of the film. “Are you?” I ask. “Yeah, I am,” he says.

Rousteing is willing to be seen as vulnerable. It’s that most human quality he hopes to telegraph alongside the glamour. “I thought if I do a documentary, it’s not going to be all about the glitter and bling of my shoulder-pad dresses,” he says. Ultimately, he wants to give others hope. “Our generation is going to suffer because our world revolves around performance,” he says. “But the documentary shows the loneliness of a guy who is seen as on the top of his game, and the message is, ‘Don’t always believe what you see.’”

And don’t mistake the raw honesty for pessimism. After an unimaginably tough year, Rousteing posted a sunny Instagram reflecting on everything that transpired: “Enjoy life every minute, spread love as much as you can, live your life with passion, and be surrounded by people that matter,” he wrote. His optimism is hard-won. “If there was no fight over the past 10 years, there would have been no winning,” he says.

This piece originally appeared in the March 2022 print edition of Harper's USA.

Feature Image: @olivier_rousteing/Instagram

Images: Pinterest