The business of naming aesthetics

From cottage core to indie sleaze, here's how we put words to the clothes, eras, and places we can't quite define

Back in 2022, Neil Shankar found himself visiting the same kind of shop, various iterations of which were sprinkled all across San Francisco. Each had an array of similar merchandise: fancy olive oils, tinned fish, furikake seasoning. So, Shankar, who works in tech but has a TikTok channel with commentary about modern branding under the name @tallneil, posted about trying to find cool brands IRL. Somewhere in the mix, he included a throwaway comment, categorising these spaces as “shoppy shops.” The video itself didn’t majorly move the needle—he barely remembers what it was about—but the phrase stuck like glue.

You hear the name “shoppy shop,” and you can immediately visualise what he’s talking about, from the pale wood shelving down to the branding of fancy food labels. Emily Sundberg, writer of the Substack 'Feed Me', picked up the term in a story for Grub Street titled 'Welcome to the Shoppy Shop' in January of 2023, and it quickly took off, spawning countless TikToks and incendiary Instagram dialogue. The term has since caught on colloquially, much in the same fashion as quiet luxury, blokette, or girl dinner—and this TikTok-fueled formula has been repeated over and over and over again.

There’s something so satisfying about seeing yourself in a trend. Girl dinner? I eat that! Cottage core? I dress like that! Shoppy shops? I’ve been there! Actually, I’ve been to a lot of them… It scratches an itch to make sense of our world, to put a name to these patterns. Shankar was just “trying to make sense of the experience of going to these shops.” Talking to other people about them, trying to Google them—“I found myself not knowing what to search or how to express that interest and pursue it,” he recounts. Naming a trend “lets you put your finger on something kind of abstract and conceptual,” says Shankar, “especially if it's something that hasn’t really had a name before.”

Evan Collins runs the nonprofit CARI, or the Consumer Aesthetics Research Institute, which is responsible for bringing terms like “indie sleaze” to the masses. He works with a team of volunteer design researchers to aggregate and categorise aesthetic data—and each category then needs a name. “It's very important that the terms be overarching and descriptive enough to really encompass as much as possible about that particular style, but, at the same time, be super succinct,” says Collins. At CARI, they often start with a long list of adjectives and whittle them down democratically. For example, global village coffee house, which encompasses the spaces of these tribal-inspired coffee shops popular in the late 1980s and the style spawned around them, is already “a little long in and of itself,” but it began as “Millennium-Era Urbane-Sophistication 'World Vibes' Aesthetic.”

He explains, “We try to make them super snappy, not to be a marketing term, but to try to have it catch on in the overall language as much as possible.” One he’s still amazed at the success of: “whimsigoth.” Like shoppy shop, it captures the essence of what it describes—and has subsequently blown up on TikTok. Indie sleaze, shortened from one of the original 'proto-CARI' Facebook Groups titled “indie uber-sleaze”—was succinct and effective.

Most of these trends aren’t named by professionals though; they’re named by amateur creatives on TikTok. Even so, you see patterns emerge in naming schemes. “You can tag core onto anything, and it instantly intellectualises it,” says Shankar. Other common suffixes are -girl, -aesthetic, -ette, -summer. (It’s not lost on us that these are quite femininely connoted.) “I feel like stickiness and playfulness is a big part of this, especially on TikTok,” he says. “I remember when girl dinner became a thing and it was just so perfectly described what it was. Or cottage core. When you hear a name that fits the thing that you've seen so well, it retroactively helps you process information.” It helps brands process information, too.

A proclivity towards tinned fish has been in the ether for years now—as has a broader aesthetic that has emerged in its orbit. So much so that late spring of 2025 saw the rise of the much more specific “sardine girl summer,” giving this abstract trend a very specific name. Staud, an LA-based lifestyle brand that caters to in-the-know young women looking to shop at a moderate price point, released their “staudines” tin clutch and beaded bag this summer in response. Both have done well in terms of sales; the latter is one of their top performers site-wide.

Shankar saw a similar response to Shoppy Shop. The Big Night, a quintessential shoppy shop based in New York, launched a tote bag with the term emblazoned on its front at the beginning of 2023, right after the Grub Street article ran. It sold out in a few days, and the brand had to restock their order multiple times. “The running joke is that brands are always late to the party, and their participation in the trend is not always welcome,” Shankar reflects. “But with shoppy shops, I think Big Night was the first to really lean into it, and they really embraced the term in their own branding.”

It’s an easy step-in for creators, as well. “I don't need to make a video about cottage core,” Shankar theoretically muses. “I can just say the word ‘cottage core’ in a video, and it feels like I'm participating, speaking to a specific audience.” This categorisation lets communities bloom around the different microtrends.

Technically, this concept of naming trends is nothing new; it’s just completely changed in scale and scope. Take, for instance, art deco, which is generally thought of as existing from 1919 to 1939. It’s named after the Exposition International des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes, but that name wasn’t bestowed upon it until a period of scholarly appraisal in 1968. Art Deco was initially just known as “le style moderne.” Today, we name things as quickly as possible. It's often much harder to name something in the middle of it than it is retroactively; you haven't really seen it all yet. But to let a collective experience go unnamed would be a missed opportunity for sales, traffic, community, you name it.

“Some of these newer trends and 'micro-trends' seem to be intentional attempts by agencies or corporations to drive engagement, or to whole-cloth generate new consumer lifestyles and subcultures they can then curate certain products/services around,” Collins posits. He and his team deal in what they call “consumer aesthetics,” which are much more substantial and often dealt with retroactively, versus these more fleeting microtrends. And he’s quite critical of the marketability of the latter. On the other hand, “I think there's a growing need to be able to carve out a personal or subcultural niche out of our current giant mess of social media fatigue and meaningless consumerism.”

There’s so much more available to consume today, thanks to the internet and social media; we have access to imagery like never before. “There's a desire to express yourself, to create a community with a group of others sharing common interests, and in turn develop a sense of shared belonging and identity; creating a singular term that people can search for and coalesce around really helps with that goal.” And it's an opportunity waiting to be capitalised on.

This article originally appeared on Harper'sBazaar.com

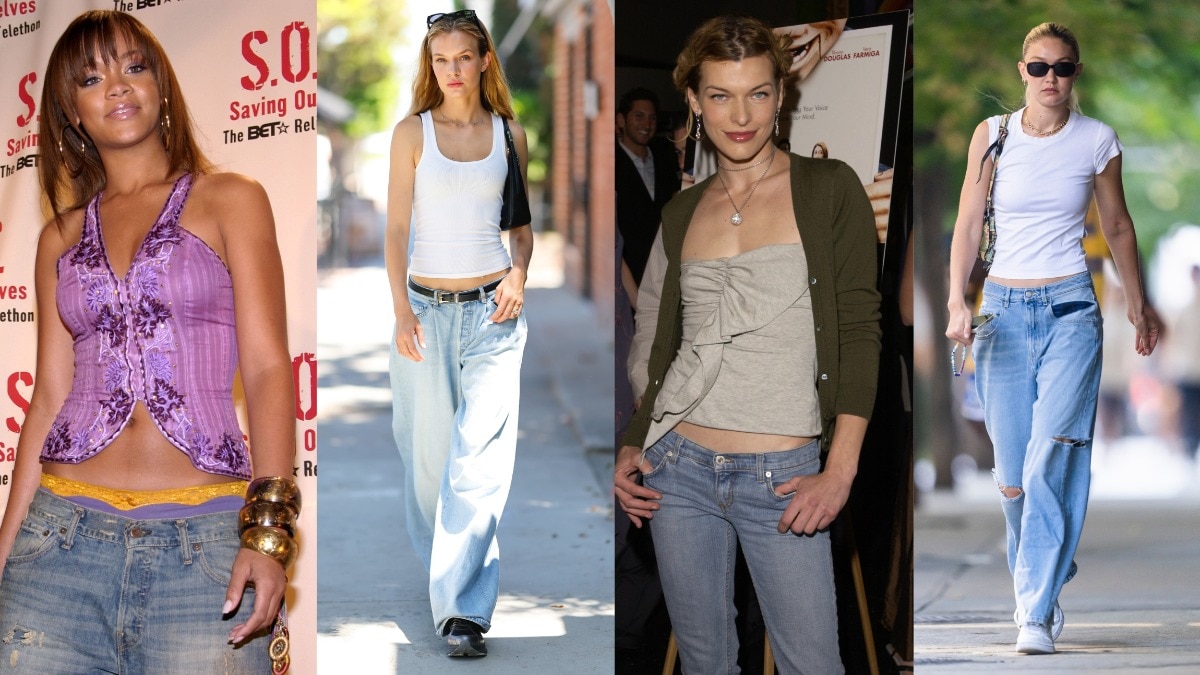

Lead image: Collage by Sarah Olivieri

Also read: Fall wardrobe staples that you’ll want to wear all year

Also read: The runways are full of primary colors. Here’s how to wear them