Ritwik Khanna on what it takes to rebuild a sustainable ecosystem

From upcycling denim, exploring natural patina, to driving a zero-waste remanufacturing system, the designer is working towards rebuilding a sustainable ecosystem.

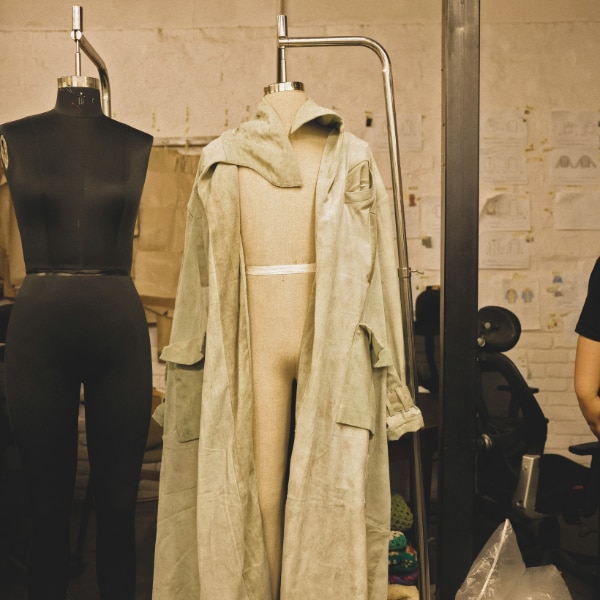

It's just days ahead of Rkive City’s digital presentation at Milan Fashion Week and an exposition in Paris to present Reclaim the City S/S ‘26 collection. Ritwik Khanna is caught up in a meeting, and the team lets us take a look around the studio at The Dhanmill, Delhi, which also doubles up as his workshop. Some of the clothes on the racks are part of the new collection. There’s an eclectic mix of his signature recycled indigo-dipped denim, beeswaxed duck canvas, block-printed shirts, aged workwear, repurposed leather, and old parachute. My colleague points out—it’s a whole different ‘vibe’ from the designers we have been featuring in our ‘At the Atelier’ series. Khanna joins us midway to take us through the collection, and most importantly, decode the ‘vibe’ that Rkive City is.

The 26-year-old designer is fidgety, and it doesn’t take a genius to make out that he has a lot on his plate. But no amount of stress can mask his passion once he starts talking about the brand, a research and design house, where post-consumer textiles direct a threepart solution—re-wear, repair, and reconstruct. “Reclaim the City proposes revival not as nostalgia but as an act of conscious reimagining; of garments, of urban space, and culture. Look around, nothing is new…from the t-shirt I am wearing to the stuff lying in the store,” he points at the exposed brick walls, old trunks, table, repurposed upholstery on a couch, and his screen-printed white t-shirt. Khanna’s philosophy lies in recontextualising how, in India and the subcontinent, we have always been mindful about reusing, repairing, and rewearing ‘stuff’. In just over two years, he has built one of the most talked-about brands in recent times, known for his purpose-driven, transformative approach to fashion. He won the R|Elan Circular Design Challenge last year and showcased at Lakmeˉ Fashion Week early this year.

Khanna’s purposive beginnings trace back to his time at the Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT) in New York, as a fashion business management student. While college taught him how to be a part of the system, he shifted his focus to questioning the order. Coming from a textile business family in Amritsar, he was into the thick of the manufacturing side of things. “We make stuff, they [the West] consume it. You spend 10 cents on making clothes and 90 cents on selling the stuff. That means 90 per cent of the effort you’re putting into selling and the remaining 10 per cent goes into making.” He questioned everything, “Why would anyone keep something for a long time? We buy clothes and end up giving them away—where did these clothes go to die?”

These questions made Khanna delve into the second-hand market in New York. He invested in archival Raf Simons and Rick Owens, and resold a lot of vintage clothes, but soon realised that it’s only one per cent of the discarded clothes, because not everything stays in trend. “To give you an example,” he points to one of the clothes, “That’s an old, boring office shirt, which has been re-block printed into something else. Now, I could maybe deconstruct it after five years of use and dye it into an indigo hat. It’s about how you’re able to look at material as something replaceable.”

He dropped out of college during the pandemic and started working in textile waste management facilities back in India. Recycling companies, some handling fibre-to-fibre recycling and others working on chemical recycling, were proposing new technology for breaking down fibre into a new polyester. For Khanna, the idea defeats the purpose as it’s not truly circular to be broken down again. He researched extensively in this space, “I started asking the right questions to the right people and learnt along the way that this system that exists, either you feed into it or you feed out of it. I chose to feed out of it by making new things out of old stuff that have onetenth the impact of what you might otherwise have.”

For an idea to live, it has to work, believes the designer. India shouldn’t be restricted to just a textile country anymore. There has to be intrinsic value within what the next wave of fashion and textile innovators hints at. “We have largely lacked in terms of global brand identities, but still have designers like Karthik Kumra and others, we collaborated with. We have a shared vision of what the new India is, what everything that we’re building is going to sum up to, and what we’re going to inspire people to do. It is one of the primary reasons we participated in the Circular Design Challenge.” It is not about being ‘inventive’, it’s more of an ideology, adds Khanna. “I’m not a scientist. I am just redirecting you to existing practices. People keep saying to me, ‘you’re too literal with things’. There’s so much happening at the moment, and we don’t have time to be in a story.”

For Khanna, the foundation of the contemporary design landscape of India lies in shared resources and shared knowledge. This, in turn, has shaped one of the prime facets of his brand identity: Collaboration. Starting with Kartik Research, The PDKF Store, Reformary (a material science research and design house), to Flying Flea by Royal Enfields—he has worked with innovative design houses to expand his remanufacturing system, share best practices, and educate people about the brand’s functional ethos. “People need to know they have an option. As a research and design house, we give them an option—either a turnkey solution, rather than making new jeans out of 100 per cent cotton denim using ‘x’ amount of water, why don’t you tastefully upcycle post-consumer denim, or we could also make those for you. The end goal is to make an impact with this idea and normalise it in the process. India always has a stigma around old clothes, despite being the place where you were handed down things.” Rkive City is for owners, not buyers—it’s this narrative that Khanna is trying to establish from day one.

Denim has been upcycled for ages—its longevity and popularity made it the first choice of material for Khanna to start the conversation. “The larger goal is to show the scope of things. You have denim, canvas, old shirting, t-shirts, polos, post-consumer leather, old parachutes, army bags, tents, old camo from uniforms, office trousers…This is all the stuff you see in your parents’ wardrobe, things they don’t wear anymore. You should be able to reconstruct it and make it into something else. And that option is what I want to give people.” Along with the scope, the designer nipped the rising concerns around scalability right in the bud. “Last year in Paris, somebody told us we won’t be able to give them 50 of the same piece. We upcycled 20,000 jeans in the same year. You can’t question the idea as you haven’t seen my infrastructure. You don’t know what we’ve built,” Khanna shares with confidence.

When it comes to design vocabulary taking precedence in Khanna’s overarching narrative of circular fashion, a lot of it is about what he and his team would wear. But it stems from certain influences in his life that have shaped Khanna’s sartorial choices. From visiting the children’s clothing store run by his parents in Amritsar, to his boarding school uniforms in Mayo College, the designer tells me how he doesn’t wear more than five silhouettes, including jeans, shirts, t-shirts, blazers, and jackets. “Those are the things that you’ll see here. We don’t need to over-engineer what already exists. We’re talking about pure functionality. My narrative is more in the process of things.” Even in the global sense of waste, when you’re sorting through clothes, it’s always the common stuff like shirts, jeans, trousers, blazers, vests, leather jackets, denim jackets, and dresses. It’s the tales told in natural patina dyes, patchwork, embroidery, and colour blocking at Rkive City.

“The kind of fading and colour matching will make you question how three pairs of different trousers went into the making of a single blazer. People ask questions like ‘How do you get it to look like this’? ‘Is that even reconstructed’? When the customer who walks in here can question that, it means they are interested in buying a good product, well-made, well-finished, meant to last, and not because they saw somebody wearing it on Instagram.” All the karigars are trained in-house, although initially it involved a lot of convincing and reasoning as they weren’t used to working with textile waste. Deconstruction is one of the primary processes that everyone is well-versed in. It lays the foundation for repair and reconstruction using simple pattern-making.

The concept of revival is not new in India, but it has become the larger conversation of craft, which has been revived and contemporised as well. “You make beautiful textiles that are meant to last. Designers and brands like Sanjay Garg of Raw Mango, Studio Medium, NorBlack NorWhite, and Kartik Research are reviving so many cool things. When it comes to post-consumer textile revival, everybody wants to do it, or wants to be able to do it,” explains Khanna. But it is incredibly hard to do it over and over again, and that’s what most of his time gets spent on. To build a system where everybody should be able to do this, and once that bit is done, to educate others as well—this will take time and effort, he is sure. “Some of the biggest waste producers also happen to be the ‘cool’ brands, and nobody holds them accountable. They have to join the conversation by coming to people like us and others who have been doing this for a while now. There will be more to follow, hopefully, and that will make us nothing but more than happy because this supply chain is going to move faster, there’s going to be more infrastructure. It is easy to make expensive clothes that are high quality; it’s expensive to make something that’s affordable, high quality, and will still have an impact,” Khanna concludes.

All images: Tongpangnuba Longchari

This article originally appeared in the Harper's Bazaar India June-July print edition.

Also read: All the highlights from Hyundai India Couture Week 2025

Also read: How South Asian creatives are taking the global stage