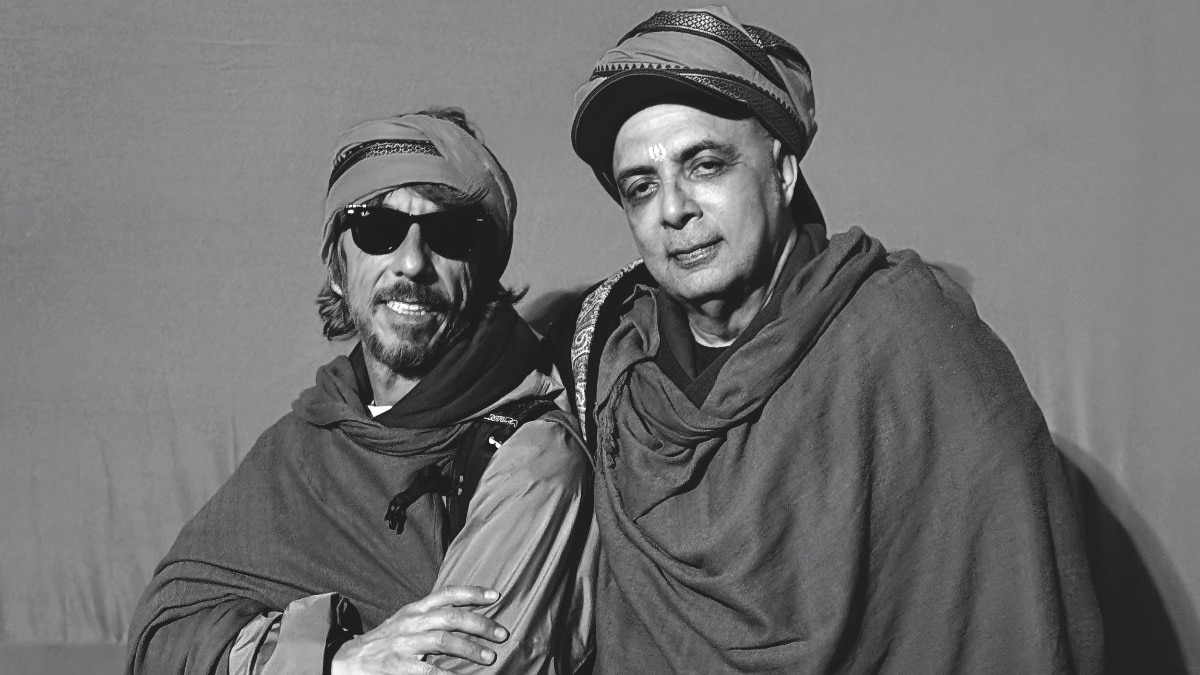

Couturiers Pierpaolo Piccioli and Tarun Tahiliani embarked on a journey in search of drapes and colour at the Kumbh Mela

The hitchhiker's guide to the sartorial galaxy on the banks of the Ganga.

It was a cool Monday afternoon when couturiers Tarun Tahiliani and Pierpaolo Piccioli boarded a private jet in New Delhi. It was the Italian designer’s maiden voyage to India and he joined Tahiliani’s merry band of travellers on a journey to the Kumbh Mela. “And then we’ll ride to the Ganga in a chariot,” Tahiliani said animatedly as they took off with a veritable list of who’s who. Their destination? Prayagraj. In Prayagraj, hordes of people walked along the banks of the Ganga. Aluminium plates transformed the sandy banks into temporary pathways. Barefoot men and women dodged puddles of water while balancing their belongings atop their heads. The chants of mantras from speakers, calls for free food from akhada (monastic) kitchens and the banter from the pilgrims illustrated what the nervous policeman described as the onslaught of the Great Indian Public. “More than 10 million people are headed this way,” he said as he ushered the crowd past a barricade on the eve of Makar Sankranti, a festival that marks the onset of the harvest season. With merely 50,000 members of the police force on duty, the constable was flustered. “Ten people are lost,” he said. As a crowd control and law and order measure, orders from the state government dictated that the roads leading to the sangam (the confluence of the rivers Yamuna, Ganga, and the mythical Saraswati) be transformed into a ‘no vehicle zone’. Soon after the orders went into effect, the jet carrying Tahiliani and Piccioli touched down.

The Maha Kumbh 2025, touted as the world’s largest human gathering, carried greater significance because of a rare planetary parade. A once-in-144-year celestial spectacle, with the moon, sun, Mercury, and Jupiter in alignment, gained traction on social media, adding to the virality of the moment. That’s how Piccioli first learnt about the event while researching spiritual gatherings in India from Nettuno, his seaside hometown about 60 kilometres from Rome. In a year of great personal transformations, Piccioli had the urge and time to travel, but he pushed the idea aside, dismissing it as wishful thinking.

In Delhi, Tahiliani was deep in his archives, studying images from his Kumbhback Collection that was inspired by his visit to the Maha Kumbh in 2013. He browsed through images of ‘holy men’. He studied their drapery and recalled the moment his eyes opened to the limitless possibilities of the draped form—free and unfettered, unconscious in its caress, primordial yet sensuous.

“I always knew I’d return,” he said. A small group emerged as the guest list kept growing: Tina Tahiliani Parikh, Subodh Gupta, Vikram Goyal, Rohit Chawla, Sumant Jaikishan, Malini Ramani, and counting.

The call to pilgrimage is a tryst with faith, and as chance would have it, Piccioli received an invitation from India. He read it as a sign and couldn’t say no. So, he began planning and researching the trip, cautiously avoiding looking at any images. His aim was complete immersion without preconceptions. “I had to simply record and witness what I saw, and never judge,” he said.

That’s how Piccioli ended up in a car with Tahiliani, driving through the busy streets of Prayagraj on his second day in India. He took in the rush of humanity, attempting to capture each step. A Leica camera hung around his neck, his iPhone was always handy, and a Kodak camera was in his backpack. The banter in the car came to an abrupt stop when the car was pulled over by a police constable at Medical Chowraha, a busy junction in the city.

“Padyatri,” the police officer gestured with his hands. Henceforth, it was a pilgrimage by foot. No more cars beyond the barricades. Tahiliani glanced back to the trunk of the car that was loaded with seven bags including one which had clothes for the group. It wasn’t some design fantasy but a belief Tahiliani articulated with clarity. “There should be no hierarchy in a place like Kumbh. I wanted us to blend in. The looks were a common denominator.” He imparted some fashion advice: “I am bringing extra saffron fabric and accessories for everyone. Please stick to the saffron theme; coral is a preferred choice of accessory, along with rudraksha instead of Golconda diamonds,” he wrote on the WhatsApp group.

With no persuading the police at the barricades, Tahiliani began fretting. Nobody was in the mood to walk for seven kilometres. There were thousands of people on the streets and Tahiliani watched in awe. “It’s the Maha Kumbh, but there’s also the hype on social media,” he said. Busy working the phones from the chai stall on the road, he called the camp manager and Laxmi Narayan Tripathi, the High Priestess of the Kinnar Akhada and a transgender rights activist. “Send help,” he urged them.

Meanwhile, Piccioli clicked away, stunned by the crowd. Some carried heaps of their belongings on their heads wrapped in cloth, others dragged suitcases. “I wanted to live the culture and not be an outsider, a tourist,” he said.

Two hours of confusion and calls later, a flotilla of eight motorbikes from the camp and a car from the Kinnar Akhada reached the barricade. As the sun set over the Ganga and a chill fell upon the city, they rode off on bikes. The car with the suitcases took off in the opposite direction. On the back of the bike, Tahiliani pondered the duality between physical reality and spiritual awareness. By then, Piccioli was lost.

“Where’s Pierpaolo, he doesn’t speak Hindi, he’s on a motorcycle, lost. Oh my God,” Tahiliani shot out a message.

For Piccioli, who wanted to ride to the Kumbh on a train with goats, the bike ride down the gullies of Prayagraj—lined with saffron in different textures and shapes—was a treat. Piccioli is a colourist hypnotised by the magnetism of hues, boldly mixing mint green and blackcurrant purple; who made the most vivid shade of fuchsia a hallmark of his aesthetic; has a signature shade, PP Pink, named after him. In his worldview, colours go beyond symbols prescribed by society—they are emotions, deeply personal. “Colours aren’t social constructs,” he ruminated.

As the bike dodged people, he saw an India bursting with colour. Away from the tedium of life, Piccioli found a form of freedom.

It was a year of new beginnings. After two decades at the House of Valentino, he departed his celebrated role as the creative director. Piccioli’s years were marked with ushering in modernity while remaining true to the grandeur of Roman tradition. In his collections, religious artworks were often a starting point where Piccioli married divinity with fashion. He studied monastic minimalism and sacred rituals while borrowing the dramatic shapes, silhouettes, and volumes from religious artworks he faithfully reinterpreted.

While Piccioli may be devoted to sculptural purity and Tahiliani to drapery, for both designers, garments are conversation starters that possess the power to elicit emotion. In the week leading up to the Kumbh, Tahiliani assigned himself an interesting task: How best to capture the humble complexity of the draped form inspired by the asceticism of naga sadhus whose denunciation of materiality led them to shed their garbs. Would it be possible to encapsulate beauty without pretence? He found the answer in the angavastra, a humble rectangular stole worn during religious rituals that is draped over the torso. Soft cotton was dyed in three colours—maroon, orange, and tangerine—and the edges were frayed to best mimic the attire of the sadhus. The look would be topped off with rudraksha malas as a tribute to the sacred.

For their part everyone in the group dressed on cue. Each member of the group received an angavastra, a bright orange cloth and drop crotch pants inspired by scenographer Sumant Jaikishan—who laboured over concentric bindis, his signature look, in a tent on the other side of the mela. When the group assembled, DJ Ma Faiza appeared with a floral head crown and Dinesh Vazirani, patron of the arts, played with his drapes. The group was ready to journey to Tahiliani and Piccioli’s camp but were stranded. The boatman who’d promised a late night ride on the Ganga answered his phone in deep sleep. He wouldn’t be showing up. Invigorated by their get-up, encouraged by the promise of the night, some jumped into a truck with a fishing net. Seven others piled into a rickshaw with people hanging off the back.

It was past midnight and the crowds were nowhere to be seen, huddled up in rows of tents that spread out into the vastness. The pack of motorbikes zipped through the main thoroughfare and deep into the pop-up mega city. It was enormous with 4,000 hectares divided into 25 sectors, 450 kilometres of roads, 67,000 street lights. Deities with cosmic rays and neon lights set the sky ablaze all the way to the Kinnar Akhada.

Dishevelled by the long drive, Tina Tahiliani Parikh— Tahiliani’s sister and the very first woman he designed clothes for—unwittingly played muse once again. She tried to mould three metres of fabric worn over a puffer jacket. “The garment engulfed me, but Pierpaolo saw the potential,” she said. So he swooped in.

“May I?” Piccioli asked and an impromptu styling session was underway. He tucked it along the shoulder, swept it ahead, and created an asymmetrical top giving the unstitched fabric shape. “I didn’t want to be a couturier at the Kumbh, but at that moment I was giving a piece of me to them. It may not be the right way of draping but it’s a part of couturier culture. It’s natural to want to create something elegant and regal on the human body,” he said.

Both Tahiliani and Piccioli believe in the designer’s uniform and are seldom seen in any shade other than black. At the Kumbh Mela, they both wore maroon, giving the look their own spin. Tahiliani wore a baseball cap, Piccioli tied an orange turban. For Piccioli, fashion is a reflection of identity. “I wanted to feel myself in such a different moment. So I did a melting of my culture and Tahiliani’s designs,” he explained and slipped on beige chinos with saffron trousers. As a token of gratitude, he draped Tahiliani, fixed Radhika Vachani’s turban, and Shalini Misra’s scarf, and it all came together. “That’s what The Look does. It gives you the vibe you want to live. It’s a sort of self-expression,” he said.

They were now ready to meet Tripathi. A former actress and dancer, her agitation for equal religious rights for the hijra community rewrote codes of tradition and patriarchy. Tripathi was now catapulted from the underground to riding a chariot to the sangam. She welcomed Tahiliani as family, in her pink velour nightie. The night held immense promise but first, she had to get dressed. Inside the compound, Aghori sadhus performed a pooja. Fire rose from the havan, a sacred pit where naked sadhus were in deep meditation. Their bodies were smeared with ash, black teekas on their forehead, long dreadlocks, and skull malas lent an urgent mystery. In the metaphysical transformation from darkness to light, with the statue of Maa Tarun Tahiliani Kaali watching over, somebody tried to explain the moment to Piccioli. “Holy ash is the last and purest state of everything,” the voice whispered.

Meanwhile Tahiliani sought the embers of inspiration that left him mesmerised during his previous visit. The sadhus drape, with multiple layers wrapped again and again around the body, were an elevated form of fluting. But something was missing this year; the drapery of yesteryears giving way to a more commercialised look. “I felt I got a lot more out of it the first time. A lot of the stuff has become very LED and pop prints. There was a purer simplicity the last time, perhaps because I was seeing it for the first time,” he rationalised. No two trips are ever the same and rolling with the Kinnars was a portal to another world. Tripathi appeared resplendent in a golden sari with dark kohl lining her eyes. She applied her bindi and tilak with a make-up artist’s precision. Tailing her was a coterie of equally decked-up women and armed guards with assault rifles. This spurred everyone into action as they moved towards the Triveni Sangam for the holy dip.

They rushed to the cars. Big burly bouncers hung off the car Piccioli was squashed in. A leading lady of the akhada hung out of the car roof window, her mobile documenting the scene. “Har Har Mahadev,” she shouted. The no-vehicle zone was packed with cars and sirens blared over restless banter. The car stopped where a sizable crowd had gathered and a human chain was formed around Tripathi. Hordes gathered to witness a spectacle. Tripathi declared Tahiliani the godfather of Indian fashion, and everyone cheered. The group was welcomed. A very tall man with an ultra-right nationalist poster approached Piccioli and Tripathi shooed him away. The women in the akhada were dressed to the nines in a parade of finery. The moment was sumptuous and excessive but Tahiliani and Piccioli had their eyes fixed on the scene in front of them.

Cold gusts of wind blew in from the Ganga but the naga sadhus stood firm. In their renunciation of material attachments, they came as they were: bare bodies covered in ash, their lithe torsos draped with orange and yellow marigolds, matted hair in dreadlocks falling down their backs or tied in large buns.

Har Har Mahadev. They lifted their tridents and swords, canes and spears.

The gawking crowd parted as queues of drenched ascetics marched ahead. A drone flew over their heads and a sadhu on an ATV circled them, capturing the scene. “Social media,” he said.

In the eruption of saffron and ash, of marigolds and spirit, Piccioli clicked an image that blended his love for colour with the traditions of India. Three naga sadhus stood together in the frame, their bare bodies draped with different materials. Yellow marigolds, ash, and a loin cloth adorned the first; the second sadhu was draped in orange and maroon floral malas topped with a turban made of marigolds; the third wore pink and coral cotton as a lungi and turban. As he watched the men, he remarked, “I found beauty where I didn’t expect to see a classical one.” The moment took Piccioli back to a look from the Valentino Fall Couture 2019 runway show. Adut Akech walked down the runway, orange marigolds cloaking her face in an orange taffeta gown. There were undeniable similarities in the aesthetic, and for Piccioli, while India was meant to be a trip centred on discovery, he was surprised to learn how much of the country existed in his subconscious. “It was as though I had India in my mind, in my soul. I’d already experienced it as a dream, I’d dreamt a long time ago,” he said.

As twilight beckoned, the group was assembled in an orange tent, awaiting their slot for the holy dip. The tent doubled up as a boardroom where members from the Juna Akhada, one of the oldest monastic orders, stopped by as a token of support for the Kinnar Akhada. Entry was tightly controlled by bouncers. Each one of the 13 akhadas are given a time slot for the Amrit Snan (the holy dip), and regular updates on who was in the Ganga made their way in the form of whispers. When the moment finally arrived, they rushed towards the chariots coming face to face with the Great Indian Public. People from all walks of life marched to the Ganga. In plain clothes, they gawked at the chariots that made their way in a procession. Pilgrims sought the blessings of those riding aboard. With Tahiliani and Piccioli in lofty seats, they sought their blessings too. This is the power of styling, someone whispered.

Perched atop the chariot, fanning the chawar (sacred whisk) used for cleansing the aura, Tahiliani watched three sadhus in rapture. The elder sadhu wore multiple layers of shaded cloth, crisscrossed across his body in an illustration that draping unstitched fabric created a fashion spectacle. On the man next to him, a humble kurta and dhoti was a nod to India’s sartorial traditions as ancient as the Indus Valley civilisation. On the young ascetic was the exquisite softness of textile worn again and again. For Tahiliani, it was a recognition of the inherent humility of cloth.

Minutes turned into hours, and the news finally came. The chariot wouldn’t move, there were simply too many people walking to the Triveni Sangam. So in the end, the merry band of travellers got off the chariot. For Piccioli, it carried deep significance. Only 24 hours had passed since he encountered this group and shared an unforgettable experience. “The night was like a thread that links people together,” he said. They walked to the Ganga, like the millions gathered with them, with nothing to offer but themselves. And as the thousands dipped in the water, Piccioli and Tahiliani’s immersion into the spiritual and mythical was a renewal, a rejuvenation in the next chapter of their journey that began on the banks of the Ganga. They all jumped on whatever form of transport they could find, lost amongst the hundreds of thousands of pilgrims, just faces in the sea of humanity.

Photographs: Rohit Chawla and Arun Sharma/Tarun Tahiliani Studio

This article first appeared in Bazaar India's March-April 2025 issue.

Also read: 5 books to reflect, reset, and rediscover yourself

Also read: Indian classical music gatherings are making a comeback with a modern twist