Why India's Sudarshan Shetty and other global artists chose Rajasthan’s viral village to show their newest works

From France, Chile, Japan, Australia, and across India, this stone quarry in Rajasthan now houses some of the finest contemporary art.

On a weekday afternoon in Kishangarh, a village in Rajasthan, a dusty service road leads me into a surreal, marble-white landscape locals casually call Snow Land. I’d often seen it on my Instagram feed as a backdrop for pre-wedding shoots, where couples from nearby cities like Jaipur, Ajmer, and Pushkar arrive with camera crews. A bride (or sometimes an influencer) draped in peachy chiffon saris re-enacts her Yash Raj film fantasy with a twirl as a drone captures it against the chalky terrain.

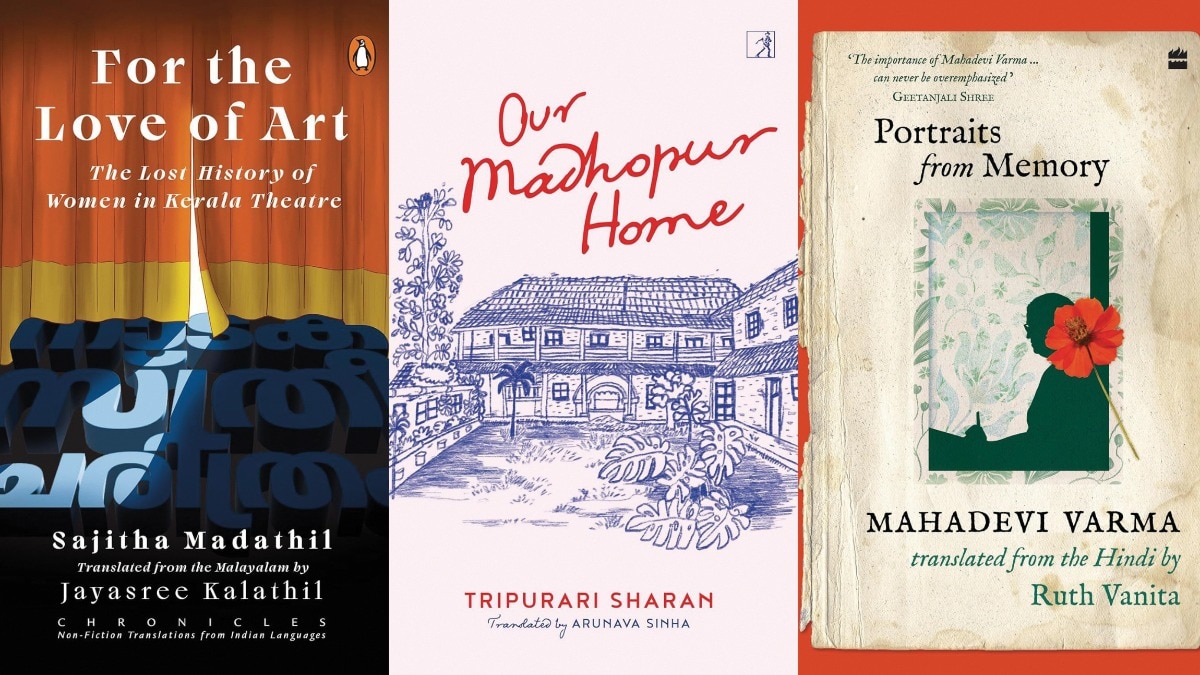

What began as a photogenic dreamscape is now on the cusp of a deeper transformation. Last month, StoneX, a marble refinery based in Kishangarh, launched Art Soirée—an ambitious project that invites a global lineup of artists, including Gigi Scaria from Turkey, Japan’s Kota Kinutani, and contributors from France, Chile, Australia and across India, to explore stone as material, memory, and metaphor. This striking intersection of viral culture and contemporary art gives Kishangarh new meaning beyond its digital fame.

Until recently, StoneX was best known as a supplier of marble for luxury hotels and sprawling homes. This collaboration, however, signals a shift: StoneX is moving from material provider to patron of contemporary art. In addition to the project, they launched a coffee table book to mark the occasion, which captures the sculptural works set against the stunning quarry backdrop. The book pays tribute to the artists' relationships with their material, especially the quarried stone, and the memories they evoke.

The artists’ works are as diverse as the terrain they now inhabit. For Gigi Scaria, working in this environment was transformative. "The experience of working here was immersive," he shares. "It expanded the possibilities of stone as a medium. I began to see opportunities for large-scale stone-based works that I’d never imagined before. The infrastructure in Kishangarh allowed for this shift in my practice."

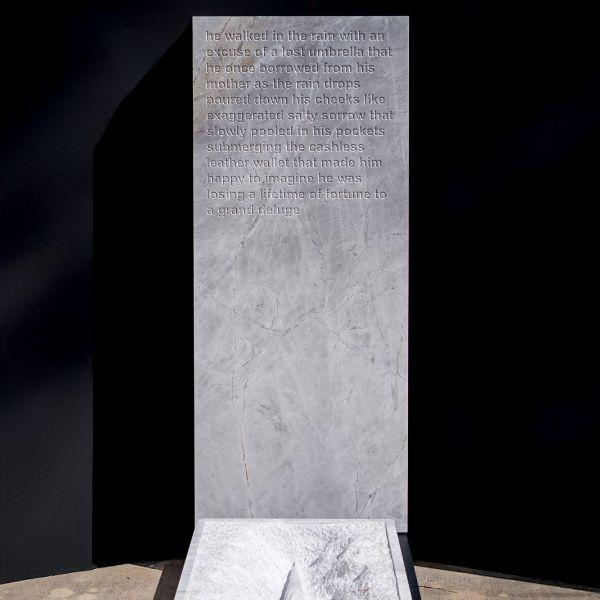

For the Indian artists, particularly, each work seems to become a dialogue between the environment, culture, and the deeply personal. Sudarshan Shetty’s Untitled delves deeply into themes of remembering, loss, and the weight of stone in the human experience. Shetty’s work interacts with the stark, minimalist landscape of Rajasthan, where the arid surroundings naturally evoke feelings of thirst, absence, and the passage of time. "The story of rain perhaps calls for a contemplation upon the arid Rajasthani landscape," Shetty explains. "The landscape’s severe minimalism and openness naturally evoke a sense of thirst, of absence. Stone, here, is not merely a material—it becomes a vehicle for commemoration, serving as both grave marker and site of veneration."

Shetty is drawn to the tension between permanence and impermanence in his work. "Working with ancient stone in a contemporary context, I find myself confronted with the tension between the permanence of the material and the impermanence of biological life," he says. "In a place where memorial stones are centuries-old yet tied to cycles of loss, sculpting stone emphasizes not just durability, but the fleeting nature of memory itself."

Japan’s Kota Kinutani own experience echoes Scaria’s, seeing Kishangarh as a place that allows him to rethink stone as a medium. "Being in Kishangarh opened my eyes to new possibilities for large-scale stone works," he reflects. "It gave me the space, infrastructure, and logistical support I needed to take my practice further." For him, the connection between traditional craftsmanship and contemporary art is key. "The global contemporary art scene and traditional craftsmanship have always been in dialogue," he notes. "It’s about finding balance between the global and the local. Kishangarh allowed me to think of stone differently—blending the contemporary with the traditional."

As traditional stonework slowly fades away, Kinutani believes the blending of contemporary art and local craftsmanship becomes more significant. "Such intersections of contemporary art and traditional craft bring a fresh dynamism and visibility to both art forms on the global stage," he says. "This fusion breathes new life into an age-old technique."

Shetty, too, emphasises the importance of preserving craftsmanship. "The traditional stonework is withering away, and as the urban landscape expands, fewer craftsmen are continuing their work," he says. "But contemporary art's engagement with this craft can help reintroduce and invigorate it, offering both traditional and modern art a unique visibility."

Even with his background in a different cultural and geographical context, Scaria feels that his work in Kishangarh resonates with both the local and the global. "Though I’ve been based in Delhi for over 30 years, working in Kishangarh allowed me to reflect on the tension between the rural and the urban, and how the global art conversation connects with local roots," he observes.

This convergence of art, site, and substance marks a new frontier in Indian contemporary practice. Kishangarh, once a dusty industrial outpost, has transformed into a dynamic stage for global artistic dialogue. The quiet beauty of the stone quarries now serves as the backdrop for a broader conversation about culture, history, and the power of materiality in art.

Lead image: Art by Teja Gavankar, courtesy of StoneX