The women who write women: Changing the narrative from within

From being tucked neatly into tropes to being flawed and full, women on screen have had a journey. But the reason women characters are being written better, in no small part, is because of the women writing them.

For generations, women on screen have turned into tropes that serve a larger story more than tell their own. Even when women began to be written as ‘empowered’, there was still an emptiness in the ‘superwoman’ trope that began to fill our screens. These were women written by men, often for male audiences, that couldn’t quite capture the nuance of being a woman in all its flawed and beautiful glory.

But then, slowly, the change that was truly needed began to come along—women writers and directors finally had a real seat at the table. Women characters began to influence the real change of women characters in Indian stories. We speak to Sneha Desai (Laapataa Ladies, Maharaj), Nitya Mehra (Made in Heaven, Big Girls Don’t Cry), and Ishita Moitra (Rocky Aur Rani Kii Prem Kahaani, Shakuntala Devi)—three prolific women creators in cinema today—about carving out women characters.

EARLY INFLUENCES

For both Mehra and Desai, scriptwriter Sai Paranjpye—the one behind films like Sparsh (1980), Chashme Buddoor (1981), and Katha (1982), amongst others—is a standout influence. “I loved her films, even though we weren’t really aware of who was writing them as kids,” says Desai. “But once I started working in films, I began to study them differently. They decoded a societal reality that would normally have been qualified as ‘art house’, but they also made so much cultural and emotional sense for the layperson. It was so impactful for their generation.”

Mehra also admires Nora Ephron’s take on the male-female dynamic: “The women in her stories were always on equal footing—they were feisty, messy, independent, and making choices that suited them. I watched these films in school. It took me a while to realise they were all written by the same woman.” Desai lists Jhumpa Lahiri and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie as writers whose female characters still have depth. “The women they write are layered, complex, well-defined arcs, full of flaws, and spunk. I appreciate that. When female characters are written with subtlety, when their feminism is intrinsic, not performative. They don’t have to shed their femininity to assert their strength, and that really speaks to me.”

Moitra recalls scanning the end credits of films for women’s names and always ending up feeling disappointed. “Apart from Honey Irani and Kamna Chandra, I don’t recall even knowing any other women Hindi film writers.” And so, Mira Nair, Gurinder Chadha, and Ephron became the writer-directors that she looked up to, as did Marjane Satrapi, Shonda Rhimes, and Margaret Atwood. “These women were able to bring multidimensionality, sensitivity, as well as relatability to women characters. A woman’s gaze and touch are very visible in their stories.”

TERRIBLE TROPES

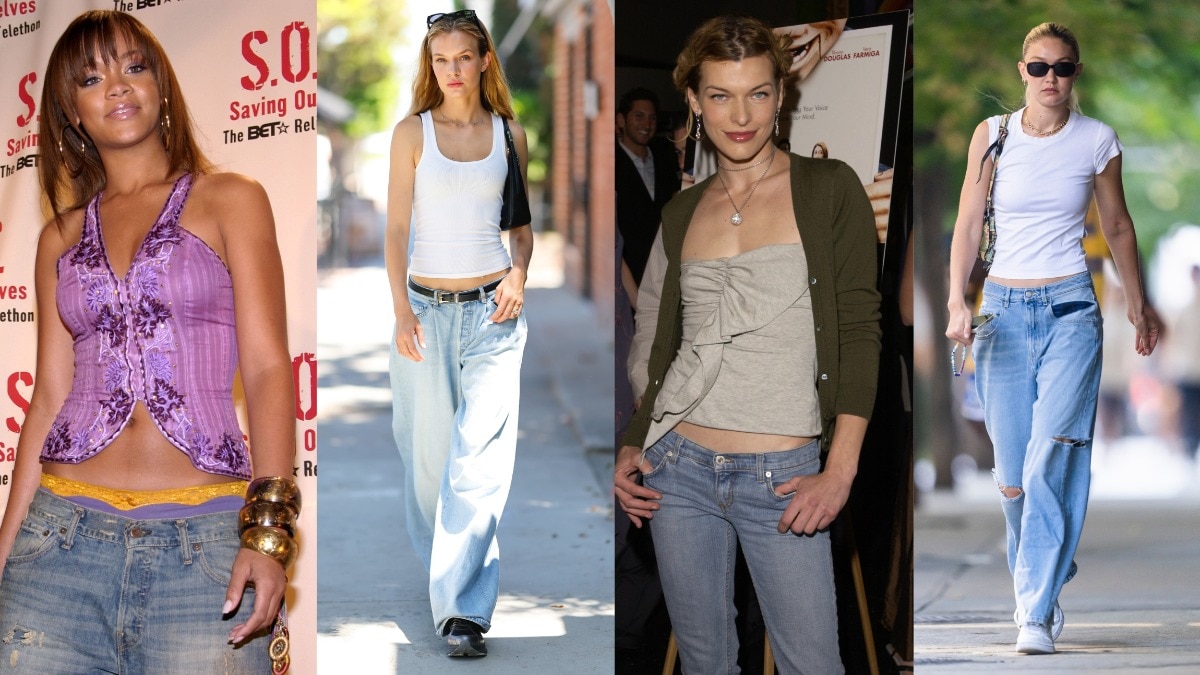

The myriad tropes that have defined women on screen have changed from decade to decade. The ’50s were responsible for creating the nagging housewife, damsel in distress, and girl-next-door. The ’60s were when we saw the appearance of the self-sacrificing mother and the sexy secretary. With the rise of horror genre in the ’70s, there was ‘the victim’, the ‘good girl/bad girl’ binary, while the ‘trophy wife’ and ‘career girl’ were antonym ideals born in the ’80s. Then came the ’90s, and the ‘cool girl’ and manic pixie dream girl came, followed by 2000s mean girl and superhero’s girlfriend archetypes. The trope of women being written to serve and propel men became so tiring that cartoonist Alison Bechdel even devised a test for it—does this movie have any scenes with two women not discussing a man?

“I love the Bechdel test. I think about the data,” says Mehra. Moitra, however, finds it too simplistic. “Just because two women are talking about relationships, it doesn’t mean the story or their arcs are regressive. Research suggests that conversations with other women often provide a safe space for expressing feelings and emotional support.”

She is, however, tired of seeing the ‘sacrificial mother and the ever-supportive wife’. “Both need to go shop for some nuance,” Moitra scoffs. “But the nagging wife who is always upset because her husband is working too hard is also extremely irritating.”

Desai would love to stop seeing ‘explanatory backstories’. “These are used as excuses for a woman’s recklessness, ambition, or flaws; but why must we always justify her choices? Let her be unapologetically herself—good, bad, or morally grey. Not every woman should have to carry the burden of representing generational trauma or morality.” Mehra wants more sisterhood on screen. “I really don’t enjoy watching women pitted against women—and it’s always for a man. It bothers me because it influences girls. It’s rooted in the male gaze, and ingrained in the way both men and women think. We need to get sisterhood into the DNA of our society.”

MEN WRITING WOMEN

Filmmaking, much like many other forms of media, has been a primarily male-dominated field for a century. Nearly all major motion pictures had a man at the helm—directing, writing the script, story, and screenplay. Women filmmakers and directors—until, perhaps, the last 15 years—who made it to the mainstream were so far between, you could count them on one hand. And writers’ rooms for TV shows—even those about women like Sex & The City (created by Darren Star with head writer Michael Patrick King), Desperate Housewives (with showrunner Marc Cherry) and Ugly Betty (by head writer Silvio Horta)—had barely any women.

“Many male writers tend to paint women in broader strokes, often as symbols of sacrifice, moulded by societal conditioning, and burdened by expectations,” says Desai. Mehra agrees, “Men will often write women as either objects of desire, homemakers, or homewreckers. It isn’t the women being written as bitches that’s the issue; desirability is great. It’s that is their cardinal trait. It’s fine if the plot demands it to move forward.”

It’s a chasm even the most brilliant directors (think Akira Kurosawa, Christopher Nolan, or Martin Scorsese) often cannot cross, writing the women in those poignant films in hollow ways. Veteran screenwriters like Aaron Sorkin and Adam McKay, who know how to craft characters with nuance, often don’t even feature women in their storylines. And the dearth of women in rooms where decisions were made about how to turn them into characters has always shown in the writing.

Moitra can tell just by reading the script. “Just the way a woman character is described can be a giveaway that a man has written it. There’s a lot more fetishising and focusing on the physical attributes, or an emphasis on the ‘childlikeness’ (kiddish traits).”

FLAWED WOMEN CHARACTERS

The tides turned with criticism about the way women were being written in the mid-2010s. But it went too far on the other extreme. Chief among them was ‘the infallible woman’; she could do everything, unstoppable, invincible—and, most importantly, unbelievable. So unbelievable, she became tiring to watch, because the overcompensation for years of compartmentalisation, the overcorrection of that trope, led to the creation of a superheroine-esque trope that still felt unrelatable to most women.

And so, the flawed women—desperately needing visibility on screen—slowly began to appear on screen; often steered by women writers.

“Strong, flawed women characters are still written cautiously. We shy away from creating women who are unapologetically ambitious, morally ambiguous, or delightfully wicked, without that backstory,” says Desai. “There’s also a long-standing imbalance in gender representation behind the camera. That’s changing now. More inclusive writers’ rooms are helping bring out multidimensional women characters who feel real, not restrained.”

Moitra feels society has conditioned women so much so that they have turned into people pleasers. “The idea is to have characters who are okay not being liked by everyone,” she adds. “Women who can actually live life on their own terms and not be burdened with ‘log kya kahenge’ (what will people say). There is a more realistic and lived perspective represented at the table and that changes everything. The characters no longer have to be derivative of other women in cinema. They can actually be derived from real women we know.”

BEING THE CHANGE

Talking the talk is one thing, but Desai, Moitra, and Mehra have walked the walk, creating strong and real characters through their work.

Moitra says she is proud of Shakuntala Devi, Captain Shikha Sharma (The Test Case, 2017), and Bae (Call Me Bae, 2024), but it’s Rani Chatterjee (Rocky Aur Rani Kii Prem Kahani, 2023) who is at the top of her stack. “I identify with her politics, opinions, her world view the most. She is modern yet deeply rooted in her culture. She values ambition and family, and doesn’t feel the need to choose between both. And when in love, she is willing to go the extra length to make it work. Most of all, she is always unapologetically herself.”

Desai admits she loved creating Phool, Jaya, and especially Manju Maai in Laapataa Ladies (2024). “They’re such distinctly vibrant women, each with their individual stories. Their journeys intersect, but their individual paths and personal arcs are radically different. Their courage varies in proportion to their unrealised dreams. They’re feminine, hopeful, submissive to an extent, but also quietly resilient.” And Mehra is proud of every single female character in her boarding school-based series Big Girls Don’t Cry (2024). “I’m so glad that we could put out a story that was authentic to the all-girls’ school life. We got messages from all over India, including many small towns, saying that the film made them feel seen.”

All images: IMDB

This article was originally published in Harper's Bazaar June-July 2025 print issue.

Also read: Are we finally ready to let Lena dunham be Lena dunham?