Elif Shafak, a multilingual novelist and political scientist, on defining her culture and identity through literature

The author opens up about a childhood shaped by absence, imagination, and matriarchal strength.

It was the summer of 1980s in Strasbourg, France when Elif Shafak’s parents separated. Only a child then, she remembers fragments of those formative years: A small flat in a banlieue along with books, cigarette smoke, and noisy university students who’d have heated debates. Shafak’s parents, now no longer tethered to each other, went their separate ways. Her father stayed back in the country and remarried while her mother, with nowhere else to go, took young Shafak to her maternal grandmother’s home in the city of Ankara, Turkey.

Shafak recalls struggling to understand her father’s absence. “I grew up without seeing him...and I don’t have any memories or pictures of my father,” she confesses. Yet, it wasn’t only his physical absence that left a mark, she later discovered that her father was an excellent parent to her half-brothers. “I always told myself that he is not capable of parenthood, but he had always been a very good father to them (…) so I always felt like the forgotten child.”

In a completely new environment in Turkey, Shafak recalls feeling like the “odd one out”. As she walked through the streets of Ankara, she noticed the “middle-class, inward looking, and patriarchal neighbourhood,” where fathers dominated the households. Ironically, despite these odds, it was here that Shafak’s sense of sisterhood took root. She was now in the care of her grandmother—whom Shafak still credits with changing her life and that of her mother. With a different view and a progressive mindset that set her apart from other women—her grandmother was—in Shafak’s words—“very traditional and spiritual (…) who was a matriarch in a very patriarchal society.”

Fearing that her daughter might follow the same constrained path she had been forced to take, Shafak’s grandmother supported her daughter’s independence by sending her to university again. At that time Shafak’s mother not only had a failed marriage, but she also had dropped out of university thinking that “love was enough.” She had no career, no diploma, no money, or a fallback plan. Although it was common for women in such situations to marry someone older, Shafak’s grandmother rejected the idea. She recalls her grandmother saying, “she can always get married again if she wants to, it will be her choice, not someone else’s idea.”

With her mother away at university for long hours, Shafak spent a lot of time with her grandmother. Although she felt loved, Shafak admits that life at her grandmother’s often felt “very boring” and “for me, storyland was far more colourful and intriguing, I wanted to go to that space of imagination as often as I could.” Which is why she considered books her companion. She would spend most of her days at her grandmother’s modest library, reading and re-reading the same books, while imagining different endings to the stories she read.

It wasn’t just books that bought her amazement—it also was the female gatherings that she was a part of. These meetings, no matter how short or long, were a space where women talked about superstitions, supernatural creatures, djinns—all without the supervision of a male figure. “It was an incredibly lively environment, and I think it shaped my writing in so many ways,” she reminisces.

As time passed, Shafak’s mother graduated and secured a promising job at the foreign ministry, which required her to relocate to Madrid, Spain. Now 10-years-old, Shafak left Ankara and was sent to an international school where she had to learn English and Spanish—both of which she was not familiar with. Her mother being the only caretaker and the sole breadwinner working for long hours, Shafak became increasingly withdrawn and struggled to keep up with her classmates.

She remembers being bullied and feeling like the ‘other’ in the classroom. Looking back, Shafak reflects, “Maybe someone else would have handled it (the situation) better, but I was an introvert and couldn’t respond.” Feeling alienated at her new school, Shafak once again found sanctuary in books. With access to a larger library than at her grandmother’s home, she found Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote—a book that opened her eyes to new possibilities and ways of existence beyond her own. “I somehow connected with the slightly foolish knight who’s looking for adventures, and is on the road and can’t quite tell the difference between fact and fiction—his imagination is his guide.”

Her flair for reading naturally led to writing, and she published her debut novel, Pinhan, at the age of 22. Written in Turkish, the book tells the story of a hermaphrodite mystic and challenges the notion of identity as a fixed and pre-given concept. Surprising the critics with her writing, the book won the Rumi Prize. Shafak used both “new and old words” in her novel saying that Turkey is “a bit polarised when it comes to language, there’s this notion that if you’re a modern, liberal woman, you’re not expected to know old words, but if you’re conservative and above a certain age, you might.” But language has always been the Turkish-British author’s passion—so she wrote as she pleased.

Continuing her literary journey, the now London-based writer went on to write several novels, including her first bestseller The Forty Rules of Love, published in 2009. A historical narrative, the novel is structured around 40 guiding principles, and each rule offers insights into love, faith, and the human experience. As Shafak explored themes of true love, and the power of embracing change—this book was not only a bestseller, but it was chosen by BBC as one of the 100 Novels that Shaped Our World.

Showcasing the breadth of her writing, it wasn’t long before her work sparked rage and controversy. Her unflinching style led to clashes with the Turkish government. In 2019, shortly after publishing 10 Minutes 38 Seconds in This Strange World, she came under investigation for writing about sexual violence. The novel offers a piercing look at the trauma experienced by women, presenting a humanising narrative of sexual violence through Tequila Leila—a sex worker in Istanbul who’s eventually murdered and her body found in a dumpster.

Undeterred by the allegations, Shafak spoke against the Turkish government’s actions, and advocated for freedom of expression and importance of literature. The novel eventually was shortlisted for the Booker Prize and RSL Ondaatje Prize.

Till now, the 53-year-old has published 21 books—13 of which are novels, and her work has been translated into 58 languages. Looking back at her career and early writings, she shares, “The biggest change from my earlier work was the change in language.” Having written her first four novels in Turkish, switching to English proved extremely challenging. “For me to abandon my mother tongue and start writing in a foreign language was so hard—it felt like cutting off the hand I write with.” As a non-native English speaker, she explains, “Every immigrant knows there’s a gap between the mind and the tongue; the mind runs faster while the tongue struggles to catch up.”

After a three-year hiatus, addressing yet another important topic—her latest book There Are Rivers in The Sky explores the politics and preciousness of water. Spanning countries, continents, and centuries, the book brings together three characters, two rivers, and one ancient piece of literature together, connecting them with a single drop of water.

Shafak asserts that as water becomes scarcer and we lose touch with nature, we must stop seeing ourselves merely as consumers of it. “Our relationship with nature is arrogant. We think we are superior and the smartest species, but we are only a small part of a fragile ecosystem. One day, human beings will disappear altogether, but the mountains will survive, the rivers will somehow carry on, and the trees will survive.”

As an ecofeminist, she argues that we can’t be single issue advocates. “If you care about gender equality, you must also care about the climate crisis.” To illustrate her point, she gives an example of the Middle East. “Where I come from, water scarcity is an acute reality. Of the most water-stressed nations in the world, seven are in the Middle East and North Africa. Our rivers are dying and there’s no fresh water nearby.” Because of water shortage, women must walk long distances to fetch water, which unfortunately increases their risk of gender violence. “These issues—water scarcity and gender violence—might seem unrelated, but they are all connected. If we care about one, we must also care about racial and regional inequality.”

As our conversation drew to a close, Shafak hopes to remind us of our profound interconnectedness, not only with one another across boundaries but also with nature itself. “And to understand this connection, we need not look further than the journey of a single drop of water."

Lead image credit: Ferhat Elik

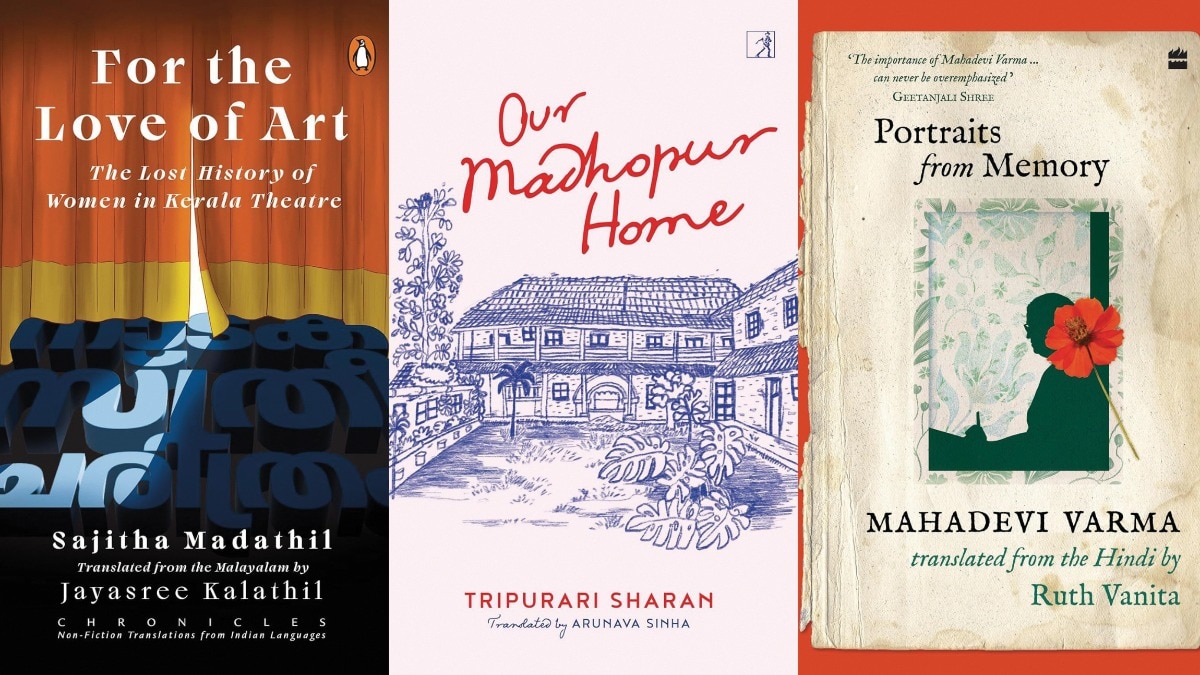

Book images: Courtesy Aamzon.in, Penguin Random House India, and Internet Archive

This piece originally appeared in the April-May print issue of Harper's Bazaar India

Also read: 5 debut novels by female authors to add to your bookshelves in 2024

Also read: Female authors explore how crucial it is that women write about their personal experiences

Also read: This author’s visit to her hometown revealed a poignant truth: grief and joy can coexist