Discover the secret to falling in love with your body

Thinking more openly about your own physique, and sometimes, asking the most complex questions might just be the key.

If I asked you to tell me everything that you liked about your body, what would you say? How long would the list be? And if I asked you what you didn’t? I’d wager your second list would be longer.

We are bombarded with ideas of what our bodies should and shouldn’t be like from a young age. ‘Should’ and ‘shouldn’t’ must be the world’s least helpful words. Yet they are difficult to escape, especially for women. And so, we do what we are told to do; what we should—that word again—do. We police our eating and jog or gym our way towards the dimensions that are supposed to be ours. Rare is the woman who isn’t permanently running some kind of calories-in to calories-out counter in her head.

For years, either I was being good—exhaustingly sugar-free, minimal-fats good—or I was being bad: blow-it-all-to-the-wind bad, eating things I thought I wanted but, looking back, I might well have wanted a bit of, but not half a packet. I never had an eating disorder, but I probably had some kind of disordered eating. When I began to listen to my true appetites, I learnt that, yes, my body did still like chocolate, but it only wanted a couple of squares, and it liked spinach just as much. The decision not to diet, ever, which had been my modus operandi for 20 years, has transformed my life.

It was a similar story when I began to tune in to my body around exercise. I had tended to be all or nothing in this regard, too. Either I wasn’t particularly motivated, or I was caning it at the gym. I always knew that I was happier when I was fit. What I didn’t properly register until my forties was that, when I really pushed myself at the gym, I would feel great immediately afterwards yet deeply depleted a couple of hours later, and it would take me a long time to recover properly. Then there was the typical gym focus on form over function. If I was trying to learn to love my thighs just as they were, not as they ‘should’ be, how helpful was it to be given a training programme specifically designed to ‘sculpt’ them?

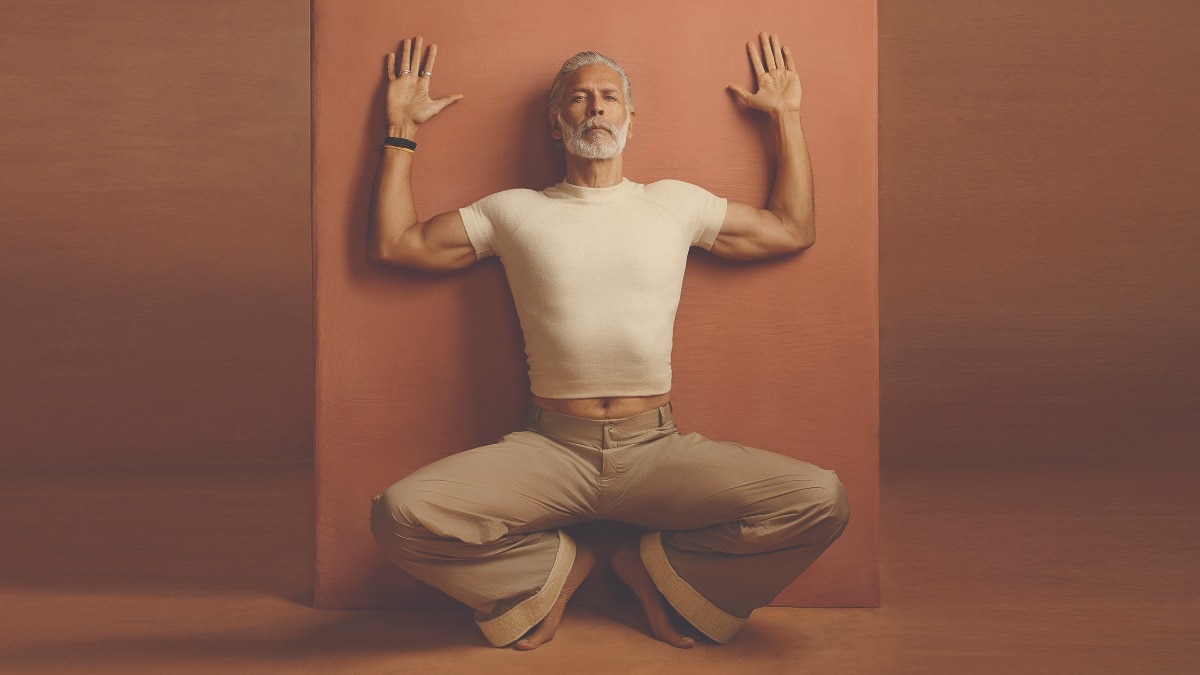

I never go to the gym now. Having discovered yoga in my mid-thirties, with its emphasis on honing your physical skills rather than drastically altering your body, and with its calm centre even during intense exertion, it was a liberation. That my ‘form’ happens, over the years, to have transformed (by way of that shift in focus) and that I am not only stronger and more flexible in my fifties than ever before, but also more visibly toned, is the ultimate bonus. What’s more, my physical strength makes me feel strong in other ways, too. While I have friends of a similar vintage who feel demoralised by what they see as an inevitable corporeal decline, I have never felt happier about my body, nor more motivated about what I will learn to do with it next.

Where did our desire to be thin come from in the first place? The feminist author Susan Bordo argues that it is about ‘the tantalising ideal of a well-managed self in which all is kept in order’. That self is, she continues, ‘decisively coded as male’, while ‘bodily spontaneities’, such as hunger and the emotions, ‘have been culturally constructed…as female.’ And so, to follow Bordo’s argument, women covet thinness as a way to demonstrate that we can do, be, live as men do.

The danger with turning your body into a kind of performance is, of course, that you become disconnected from it; disembodied. There is a weight and shape that you are supposed to be, and only you can find your way there. The secret to finding your body beautiful is key, because it is yours, calibrated to your natural appetites and requirements—is to give it what it needs, which is care and attention that is wholly positive. Once you embark on this journey, you will find it endlessly interesting, because you are, quite literally, revealing your true self. Both eating and exercise represent ways either to check in with or check out of the body and mind. Consistently eating too little is as damaging as eating too much. Consistently overexercising is as problematic as never taking any physical activity.

When it came to food, a game-changer for me was the book Women Food and God (2010) by Geneen Roth. You may already be baulking at the title. I would urge you to read it anyway. Roth, who struggled with compulsive eating for decades, believes that ‘women turn to food when they are not hungry because they are hungry for some—they can’t name: a connection to what is beyond the concerns of daily life’. To find your way out of this mess, you have to start by removing the psychodrama with which our society imbues the act of eating. Forget being good or bad. Nothing is disallowed. All that is disallowed is eating when you are not hungry.

What’s helpful is to notice the difference between what is known as ‘mouth hunger’ and true ‘stomach hunger’. How to do this? Try pausing for a moment, either before you start eating or before you eat more than you suspect you might need, and tuning in to whether the pangs you are feeling are truly physical, and thus coming from your stomach, or psychological, and so experienced more in your head and, by extension, mouth. If it’s only mouth hunger you are feeling, focus on identifying the emotion that is causing it, then sit for a while and breathe slowly and calmly through it. Eventually, you will become better at breathing that emotion away entirely. Attempting to eat it away will, in contrast, never work.

It’s hard when you start to consume differently, but if you keep practising, eventually it becomes simple. You discover, as Roth puts it, ‘that eating can finally be, and always was, for you and only you’.

Anna Murphy is the fashion director of The Times. Her latest book, ‘Destination Fabulous: Finding Your Way to the Best You Yet’ (₹2000 approx, Mitchell Beazley), is out now.