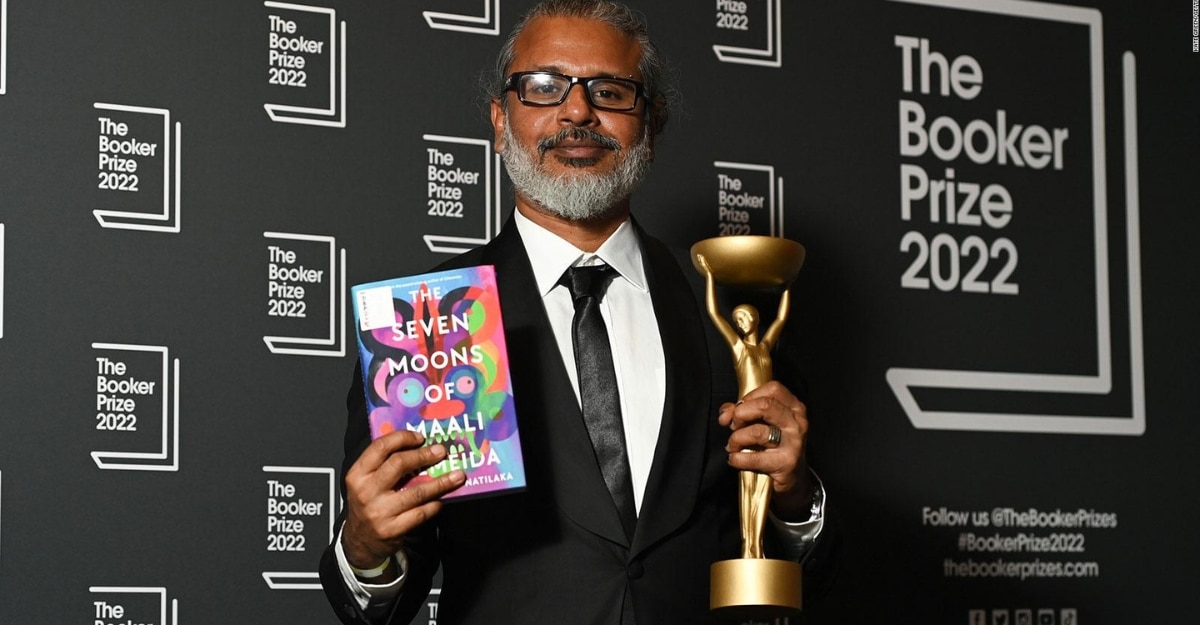

A masterclass on how to win the Booker Prize by Shehan Karunatilaka

As the author recovers from a whirlwind that were the last 96 hours after winning the 2022 Booker Prize, we chat about what went into writing a winner.

We travel back to 1989, as Sri Lanka grapples with the festering civil war. It’s a day, or rather seven, in the life, or rather afterlife, of Maali Almeida—“photographer, gambler, slut”—who has only those many moons to find out who killed him, all while leading his two best friends to a stash of photographs that will show the world what really is happening in the country. The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida is a murder mystery, a political satire, and a gay love story (“In fact, I believe that is the heart of the book,” author Shehan Karunatilaka insists)—and the 2022 Booker Prize winner has been more than ten years in the making.

As the author and copywriter talked about the years (and years) of writing Maali’s story, what came through was a beautiful (and might I add singularly patient) masterclass of what goes into the workings of a Booker Prize winner. As an author from the subcontinent myself—where even expecting to publish in the neighbouring countries, let alone the far West, is a distant dream given the preconceived notions these voices and stories are plagued with—I held on to every word in the 30 minutes of our conversation, and spent the rest of the day making exhaustive plans about how I would implement everything I had learnt. I presume there are many more of the tenacious lot, who would want nothing more than lessons in mastering the art of writing a winner, so here is a comprehensive guide.

Harper’s Bazaar: It’s been a long time of writing this book. Can you tell us about the first light bulb moment and take us through the next decade of following through?

Shehan Karunatilaka: I don’t think there was one light bulb moment. In fact, there have been many through the years. And that’s the process of writing a book. I compare it to a Cricket Test match. It is not a T-20—you don’t get a light bulb and produce a Booker novel (laughs). Yes, there is an idea that you are interested in, and you continue to interrogate it. One of these interrogations led me to Maali becoming the central character of the film. Another led me to the second person point of view to capture voice. A lot of characters emerged over time—like the dead leopard (one of the key characters if I may add). Additionally, you are always working to resolve the drama on a scene-to-scene basis. I don’t begin with knowing the ending. I have a vague idea where I may go, and I think that has been very good because each chapter you are solving a problem. Yes, it may be a long way of doing it, but it is the best way to write the story.

Also, in the early drafts, my editor pointed out that the cops, the body disposers, all kind of sounded the same—she said “these are characters, you shouldn’t be lazy with the lower-level characters”—and realising she was right perhaps was another important moment. Now each of the cops have a varying moral compass, not right or wrong because in Sri Lanka many are in the middle, but that is another thing I have liked of the process…

HB: The Booker Prize judges made a special mention of the narrative techniques that you used in the book. Were these something you chose intentionally or did they just come to you while writing the story?

SK: What narrative techniques are you talking about (laughs)? I mean, it began with a simple understanding that this is a murder mystery, so I followed all the conventions of a murder mystery. The only difference is that corpse is talking as opposed to a traditional cop-suspects-detective, and in this case the corpse is a war photographer who works for all the shady factions in Sri Lankan politics in 1989. Then as I wrote the story out things got added. I was talking about the Tamil Tigers, the Sri Lankan Army, the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna; there was also foreign influence, the arm dealers that I was exploring—and it becomes a political novel.

I don’t know if that was the intention, maybe it is. But it is also about ghosts and the afterlife, so it becomes a ghost story as well. I mean, the initial title in India was Chats with the Dead, because it was a series of interviews that Maali conducts with ghosts from Sri Lanka’s past. And the idea for me was also that the many victims of Sri Lanka’s wars were out to speak as ghosts.

Then there is the love story, a love triangle between Maali, who is a closeted gay man, and his two best friends. This, to me, is the heart of the book and Maali’s journey. And there is also the box under his bed of photographs of Sri Lanka’s unseen tragedies—photos that I presume were taken while we only saw a few that were printed and circulated.

So, yes, there are a lot of moving parts, but we always made sure to pace it as a murder mystery, because otherwise you get bogged down and there are too many details fighting for space. That was the scheme of my wonderful editor, Natania Jansz, and it was hard work, but it really came together in the end.

HB: Often, as writers, we also look for the inspiration and ideas away from the pen and paper. Where did yours come from?

SK: I would recommend reading as much of the Booker list as you can. Have you? (I stuttered the names of a few that I had.) I try to read as much of the long list as I can and have been doing so for years now. You have to know what you are aiming for. (What is interesting is that George Saunders’ Lincoln in the Bardo, which also had a talking ghost as a protagonist, won the Booker in 2017; and while Karuntilaka thought it was a masterpiece, he was at once infuriated and afraid of himself writing a ghost story, but pestered on with his work.) As for writing anything really, it begins with research, and mine, again, comes from reading books that I want my writing to sound like, watching a lot of movies, listening to stand-ups. You may say it’s procrastination, and in a way, it may be, but it all helps stitch a book together. For example, researching for Chinaman (Karunatilaka’s first novel) entailed watching a lot of Cricket and hanging out with some drunken uncles to get their stories—I mean, it wasn’t easy, but it was a lot of fun!

HB: Speaking of Chinaman: The Legend of Pradeep Mathew, how has the writing and publishing process been different from the first book to the second.

SK: I was in a completely different place in my life when I wrote Chinaman. I was single, still living with my parents. There was lesser risk and a lot more time and mental space to dedicate to writing it quickly. I remember I took six months off to dive into the book. Things have obviously changed since. I am married, have children, been in the thick of work and responsibilities. Add to it that Maali’s story is also a lot more complicated and layered, and the approach both in research and writing had to be completely different.

But the publishing process for both has not been very different, both being difficult. I self-published the first one and Chiki Sarkar in India picked it up. And over the years it caught the eyeballs it did. For this one I had agents—so there are multiple markets it has been sold to and languages it has been translated in—but getting it published was still a struggle. I went through India, and India was very receptive, but to get to the rest of the world took a lot of editing.

It has been a long journey and we can’t take it for granted that a book written in the subcontinent is going to be read in the US or the UK. There is an appetite for stories, but you really have to work hard. And it is always going to be hard. Although I suspect that publishing my next won’t be as arduous.

HB: In fact, your next one The Birth Lottery and Other Surprises is already out in the market shortly after the second.

SK: And yet it is one that has been longest in the works. It’s almost 20 years old! The first story I wrote in 2001, and it is ironically called Second Person, which is my first experiment writing in second person. This was in the 90s, and I was in my 20s, and I was trying to write but was plagued by the usual mistakes of stopping midway. This was the first story I finished.

I would write every day just for the pleasure of it. Short stories are something I write when I’m in the middle of projects, and I wrote a few over the years. It was after Chinaman that I found out and focused on writing for prizes—like the Commonwealth Prize and Sunday Times Audible Short Story Award (that is on hold as of now)—and I would enter two stories every year for these. I never got a long or short list for these; just a thank you and try again letter. But in the process, I wrote two short stories every year and, in the end, I had a collection, which is The Birth Lottery and Other Surprises. In a way I was the most unsuccessful short story writer as far as the prizes go, and sometimes I would read the winners and know why they won and would try thinking and writing similarly.

It was in the pandemic that I reflected and saw that I had a sizable collection and decided to put them all together.

Karunatilaka also has another novel, Khans, that is expected to release in 2023. When asked about it, the author said “I’ll know when it is done!” For now, he continues with his process of research and writing. “You plot out the first draft, pick it, cry at how bad and all over the place it is, get over it, and then get down to it again.” The real writers, Karuntilaka believes, are ones who do not get demoralised or sucked into the vortex that is “this is crap, I am crap, let me do something else”. They know that the first draft is supposed to be awful, but identify the elements that are interesting and pick those up to start anew.