When did doing nothing become so uncomfortable?

Millennials often associate downtime with laziness because their self-worth was shaped by achievement. But is the inability to switch off becoming less about work overload and more about the psychological discomfort of not being productive?

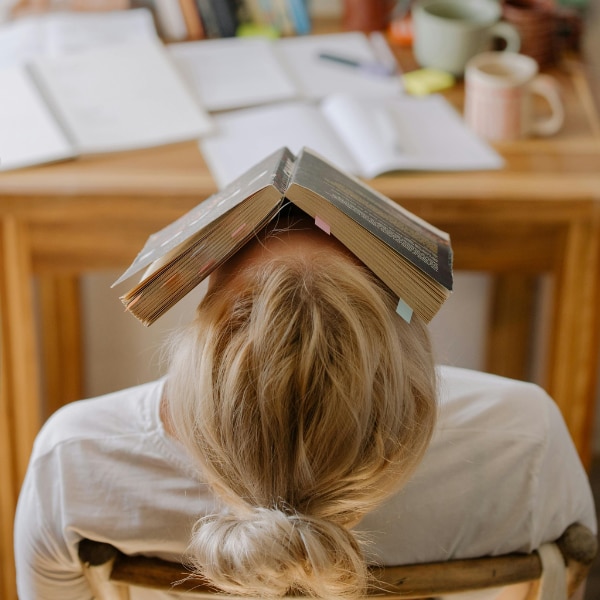

One of the many things millennials are afraid of today—apart from inflation and recession—is the struggle of having nothing to do. And I say struggle because it is a dilemma. Even though they like the idea of having a quiet day or a weekend, the reality of having to while away time with no solid plans or task list is scary for some. While their idea of a quiet begins with a peaceful day at home, it usually culminates with watching screens for hours, followed by feeling anxious about it, and finally feeling compelled to step outside for no reasonable need.

Guilt disguised as productivity

This pattern often stems from years of conditioning that their worth is measured by how much they achieve. And no, it's not about grades in school or success at work—though there is no shortage of those pressures either. It’s about the need to always be doing something useful. Somewhere along the way, they have learned that if they are not doing something to contribute or create value, then they’re simply being lazy. And that is exactly where the guilt of doing nothing creeps in.

According to counselling psychologist Ruchi Ruuh, many millennials were raised in an environment where success was equated with good grades, extracurricular activities, studying in respectable colleges, and eventually getting a good job. They internalised the idea that their “value in society is directly linked to what they can achieve.” The result? A fragile sense of self-worth, where rest feels indulgent and often carries an undertone of guilt.

“This conditioning wires the brain to equate being busy as a virtue. Doing 'nothing' feels weird and almost unsafe, because it contradicts years of reinforcement that worth is earned through constant productivity. Over time, people may lose touch with free play, hobbies, or simply not doing anything, which leaves them restless when faced with free time,” she adds.

Needless to say, this restlessness can have long-term mental health risks.

When productivity becomes the sole marker of one's identity, it forces people to push their limits because resting feels like failure. The pressure to appear busy is a constant, even when there is a pressing need for rest. And ignoring this need will only make things worse, leading to chronic stress, anxiety, depression, etc. In some cases, Ruuh suggests that such people may even suffer from an identity crisis during major life changes such as job loss, illness, or retirement. Not to mention their interpersonal relationships, which can suffer too, as partners and friends may begin to feel secondary to work.

Why rest feels wrong

So why does sitting still feel so uncomfortable? Ruuh explains that it’s largely down to social and cultural conditioning. “The voice that develops in our head keeps being critical of rest, as it equates not doing anything with stagnation. There is always a nagging guilt that whispers you should be doing more, or else you are useless or unproductive. Rest is frowned upon as it doesn’t immediately translate into something tangible or measurable like money or success. Instead of being seen as recovery, it’s framed as indulgence, leading people to experience anxiety instead of relaxation when they finally take a break.”

In other words, rest is underappreciated because it is viewed as something that can threaten a carefully constructed identity built around productivity.

Clinical psychologist Mehezabin Dordi observes this struggle firsthand: “What I often see is a deep discomfort with stillness. Even when millennials take time off, they’re checking emails, planning the next thing, or turning leisure into productivity—whether that’s tracking workouts, monetising a hobby, or curating the perfect travel itinerary. Many describe feeling guilty if they’re not ‘achieving’ something. For them, rest doesn’t feel like rest, it feels like wasted time.”

Remote and hybrid work cultures have only made it harder to step away. Because when your home becomes your office, your work seeps into every corner of your life. “There’s no commute to signal ‘the day is done,’ and laptops are always within reach,” says Dordi. “I see clients feeling pressured to be available and online at all hours because the lines are so fuzzy. They're answering late-night emails, taking calls during dinner, or even working from bed. This constant partial engagement keeps the nervous system activated and on high alert, so even when they try to rest, they’re never truly switching off.”

Reclaiming rest as a necessity

The solution, it seems, lies in a reframing of rest as an active choice rather than a luxury. Dordi suggests a few practical strategies: micro-rest in intentional 10–15 minute pauses, protective scheduling by blocking downtime as firmly as a meeting, language shifts—calling it 'recovery' or 'recharging'—and tracking the positive effects on energy, focus, and creativity to reinforce its value. “The biggest shift is seeing rest as a form of investment, not indulgence,” she says.

There is, however, hope on the horizon. Dordi notes a generational shift in attitudes toward rest and work-life balance. “Millennials came of age in a culture that glorified hustle, which is why so many of them still equate busyness with their sense of worth. Gen Z, on the other hand, is far more comfortable saying, ‘No, my boundaries matter.’ They’re more openly talking about mental health, setting limits on after-hours work, and even choosing jobs that respect downtime. Millennials often wrestle with guilt when they stop, whereas Gen Z are usually more unapologetic about protecting their energy.”

The takeaway is simple, but hard-earned: rest is the foundation of productivity, not the enemy. Learning to pause without guilt, to embrace stillness, and to reclaim free time is not laziness. It is, in fact, an act of self-preservation, a quiet rebellion against the lifelong conditioning that our worth is only as high as our to-do lists. For millennials, mastering the art of doing nothing might just be the ultimate achievement.

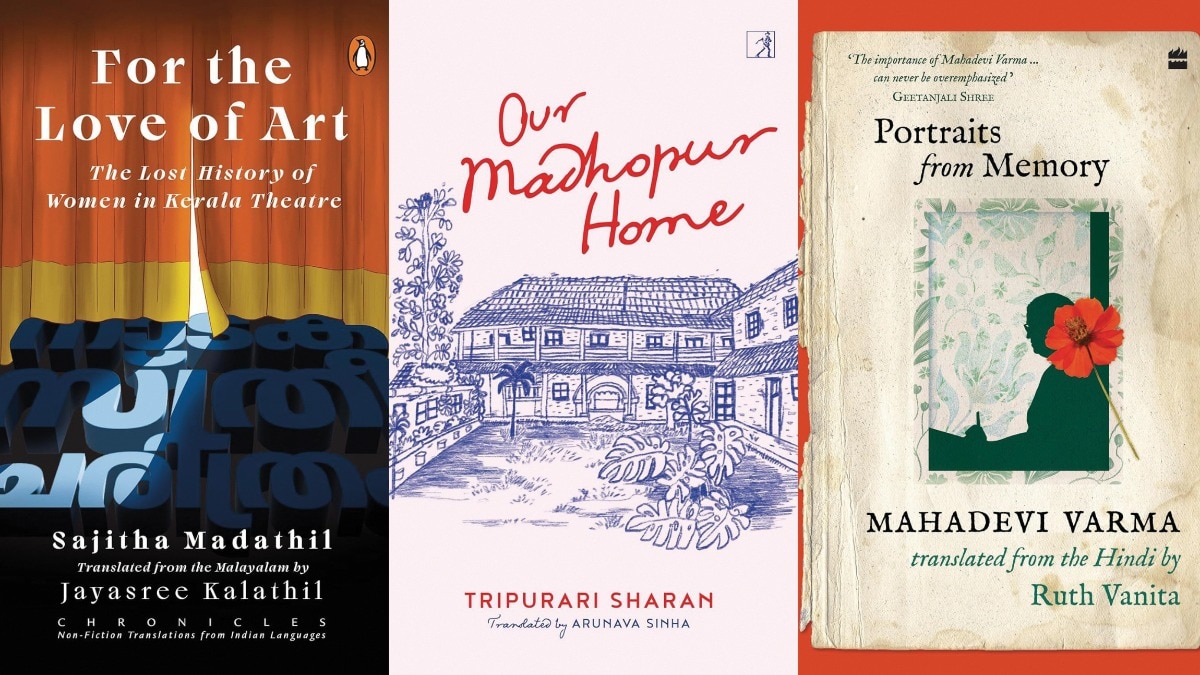

Lead image credit: IMDb; Inside images: Pexels

Also read: Are micro-routines helping us truly rest or just survive?

Also read: Why are so many people breaking up with their dream jobs?