Why the diet industry doesn't want you to know about weightlifting

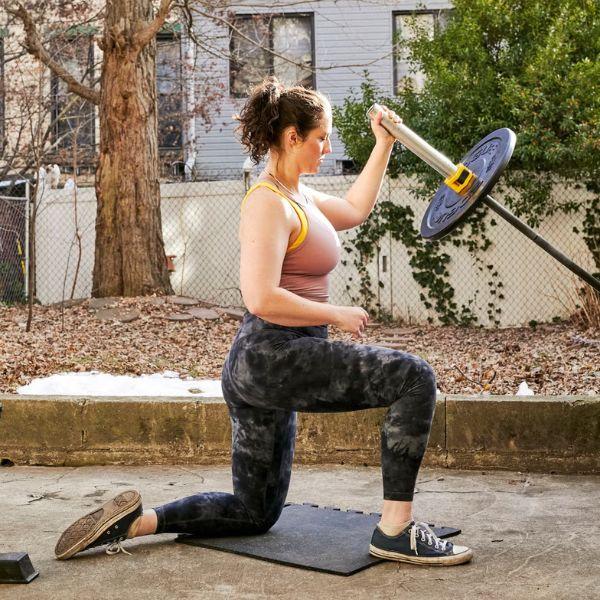

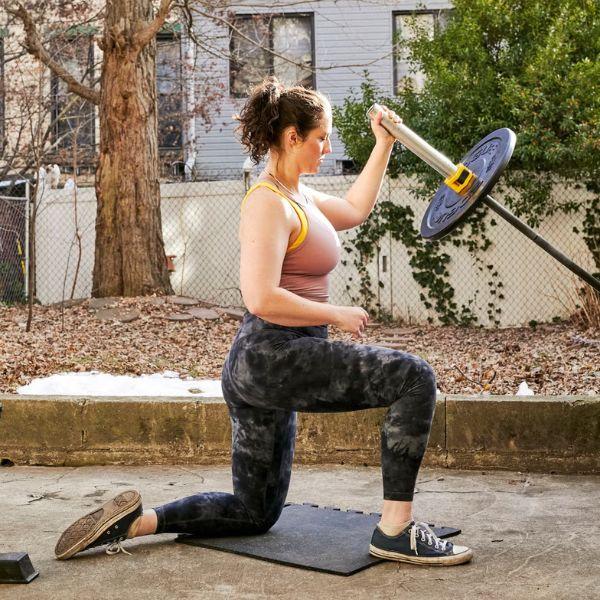

In her new book, Casey Johnston explains how weight training challenges everything we're told about how to stay fit.

For years, Casey Johnston did everything “right” when it came to health and fitness—at least according to the rules laid out by diet culture. She meticulously tracked calories, logged miles of running, and pushed herself to stay in control of her cravings. From the outside, she looked like the picture of discipline. But on the inside, her relationship with food and exercise was unraveling. “It was antagonistic; that’s how I often characterize it,” she says. “I was always fighting myself.” That fight, she eventually realized, wasn’t making her stronger. It was making her weaker.

In her candid and illuminating book A Physical Education: How I Escaped Diet Culture and Gained the Power of Lifting, Johnston maps out the journey that helped her rewrite the rules. Equal parts memoir and science writing, the book follows her pivot from punishing cardio routines and restrictive diets to weightlifting, which turned out to be the physical and emotional grounding she’d been missing. What begins as a practical exploration of strength training grows into something much deeper—a reassessment of what strength means, who it’s for, and how reclaiming it can be a radical act, especially for women.

Along the way, Johnston confronts the toxic messages she absorbed growing up in the early 2000s, a time when women’s bodies were endlessly scrutinized by the media. She also digs into the unexpected history of strength training in America, tracing its evolution from a collectivist pursuit to a domain now often coded as macho and hyper-individualistic. Her writing questions why women have been so persistently shut out of conversations around strength—and how that exclusion reinforces larger systems of control.

A Physical Education is more than a fitness transformation story. It’s a reckoning with the mental and physical consequences of a culture that tells women their bodies are problems to be fixed. Here, Bazaar speaks to Johnston about how she finally broke out of a toxic dieting and workout cycle, how weightlifting transformed both her body and mind, and why no one should feel intimidated at the gym.

What was your relationship with food and exercise like before you found weightlifting?

I hated to work out but I felt like I really had to, so I put more and more time and effort into that because I felt I always had to be losing weight. And same with food; I was always fighting myself down to eat less, because that was the counterweight to exercising more. I didn't want to “waste” all of my working out by then going and eating a lot of food. That was how I thought everything worked.

The way the 2000s addressed women's bodies was extremely unfair and gross. How much of an impact do you feel like media had on your perception of what you should look like and how you should achieve it?

It had an enormous impact. I think we're always critical of women and we’re always harder on their appearance—[how we do it] just changes its shape decade to decade. At that time there, there was so much scrutiny on the tiniest aspects of women's bodies. The dial was turned all the way up to 11. The instant response to any image of a woman was to find something to criticize. It’s not like we don't do that now, but it was intense at that time.

It was so intense! And I found it really interesting to read that you were never obsessed with being beautiful. Your pursuit to lose weight wasn’t about that.

There’s this understanding that if you're obsessed with your appearance, you are shallow. You only care about being hot, or that other people are hot. And that doesn't really explain my version of it. I felt a lot of pressure about how I looked because my understanding from both what I saw in media and how I was raised was that my appearance was going to matter before anything else about me. So at the time, I thought it was my responsibility to manage that aspect of myself as much as possible. In order to be able to gain any recognition or credit for any other aspect of myself, I had to make myself maximally visually and physically acceptable.

What was your breaking point? What led you to finally take weightlifting seriously and what about it appealed to you?

I got to a point where I was running so much and eating so little and still always trying to lose the last five pounds—but I still had a healthy BMI. No one ever screened me for disordered eating but, with the benefit of hindsight, I see the red flags. I would stand up from sitting or lying down, and I would black out for a few seconds. I was cold all of the time in my hands and my feet, and my fingernails were always super brittle and breaking off. These are all symptoms of malnutrition. I was starting to get more and more minor injuries with running, and it just wasn't doing for me what I wanted it to do. I wanted to be able to not have to think about it so much.

I stumbled across this post on Reddit of a woman who was trying out lifting weights for the first time in her life. She was like me and had no prior relationship with strength training at all, but having done it for six months, she had gotten really strong. She was eating a lot, and her body had not gotten insanely bulky like I had been promised it would if I were to ever try lifting weights. I was fascinated by this; it was like counter programming for every narrative that I'd heard about all of this stuff up until that point. She was literally working out half as much as I was and eating twice as much as I was. I was like, I have to try this. I've tried everything else.

Something that struck a chord with me was how when you first started going to the gym to try weightlifting, you were really intimidated by all of the gym bros and not knowing how to use the weightlifting equipment. You were kind of like, “What the fuck am I doing here?” which I can relate to, and I feel like so many other people can too.

I was so intimidated. Everything that I understood about gyms was that there are a bunch of meat heads there who are way stronger than you, have way more of a sense of purpose, and have way a more of a right to this equipment, because they have a greater need for it than you do. Like, you aren't even supposed to be here. What need do you have for being strong? You're a woman.

But I was compelled enough by all of the promises that post that I saw made, and by other people’s post on that forum, [ to go]. That gave me the confidence to believe that I too could have a relationship with this type of working out. I had to continue to believe that as I walked into the gym and felt intimidated in the same way all over again—it was difficult. Now, in my capacity as somebody who gives advice on this stuff and writes about all these things, I tell people that first going to the gym is kind of like starting at a new school or a new job. You don't know where everything is. You don't know anybody. You have to give yourself some space and some grace.

I even counsel people now to give themselves one session, or as many sessions, really, as they need to to just go the gym, get on a cardio machine, and watch everybody. “Okay, that guy grabbed the dumbbells, and he went to stand there. And when the person adjusted the squat rack, they did this.” When you bump it up to the next level, you do a dry run workout where you locate the equipment [you’d need], get it all set up, and not even worry about getting a workout in. Once you've done those things, then worry about getting a workout in.

When you first started, what were the transformations you saw that got you hooked and kept you going?

When I started eating more, my cravings that I had fought so hard to keep myself from eating—cookies, brownies, ice cream—all went away. I no longer had obsessive thoughts about food and that's because a symptom of being underfed is that your body is trying to push you to get more calories to feed yourself. That's what cravings are.

When I started getting a more balanced diet in order to support my lifting, things evened out in a way that I never believed they would. I thought that if I allowed myself to eat food, I would eat endlessly, but I was focused on so much else—like getting all of the food that I needed to eat—that I didn't really have to think as much about the food that I wanted to eat, although there was space to eat that stuff too.

The other thing is that I had really come to a place of feeling unequal to so many physical tasks of being a person in the world. I would struggle with heavy doors. Bending down to pick something up from the floor, even if it wasn't heavy, would be a chore. My big enemy was the 40-pound box of cat litter that I had to buy for my cats, which I physically could not maneuver in with any grace at all. Once I was weight training, I was so much more mobile, and I could do all of these things without even really thinking about them.

In the book, you look at the history of strength training in America and how it has been co-opted by both religion and the military—and how that has contributed to perceptions and stigmas around it today. Why was that important to you to include?

Something that I perceive creates resistance for some people around strength training is this idea that it's a space that is preoccupied by a lot of more conservative people—like cops, military guys, and people who might not be broadly accepting of others in the gym. There is this affiliation between strength and being super conservative.

I was surprised to learn that the at least one of the foundations of strength training in America is a socialist group called the Turners, who came about in Germany. They pursued physical education but they were also about [celebrating] German culture and sang German songs and all this stuff. It was a very collectivist group, and many of them emigrated to America in the 1800s. They set up what were called Turner Halls, which were like proto-YMCAs. They had cultural events. They pursued fitness together. They had a distaste for the competitiveness of American culture and didn't hold contests to see who was the strongest or best. They were about educating everyone. They were very enmeshed in American culture for a bit, and they actually were touchstones when the YMCA decided to institute a physical fitness component to their clubhouses.

Then, there started to be rhetoric from Christian leaders about how weakness was percolating within the Christian nation. It was the result of increasing comparisons between man and machine that came about because of the Industrial Revolution. They saw the Turners, who had this robust physical education system, and they decided to work this into all their logic, where being physically fit was of service to God.

That then translated to the idea that being physically fit is about service and labor, [which translated] to being a laborer, and then the idea that being physically fit is declassé or not what an intellectual person would do. It's what somebody does when they labor in service of someone who has power over them.

I was fascinated to learn all of this. Weightlifting is such a powerful force that it makes sense that powerful people would want to co-opt it and subdue it into this thing that is not desirable unless you're doing it in service of God or in service of a boss versus in service of ourselves and our community.

Why do you think the fitness industry doesn't promote weight training more for women? And what does that say about the ingrained misogyny within it?

There's a way of looking at it that's really conspiratorial: Smarter people than I have written about the fact that keeping women occupied with how they look prevents them from thinking about larger forces in the world, or from realizing how hemmed in we are by all of this stuff. It's particularly apt when you have a culture that emphasizes underfueling us and overworking us to the point that we're mentally impaired like I was.

The thing about dieting is, the more you do it, the harder it is to keep losing weight. The harder you diet, the more muscle mass you lose. Your metabolism goes down. Your cravings intensify. You are moved to binge on food. You gain weight back. It comes back as body fat. You're like, “Now, I gotta lose more weight,” but you have less muscle mass, so now it's harder.

So the industry has avoided weight training, I think, because it paths you out of that stuff. It shows you it's possible to become a self-sustaining force. But as weight training has become more prominent in the conversation lately, the diet and weight loss industry is finding its way to make it problematic. They focus on leanness instead of overall low weight. And that can be its own problem. It’s not necessarily better to be really muscular if you also have low body fat. We need our body fat as well as muscle. It regulates our hormones. We use it to store certain vitamins.

Throughout the book you talk about a relationship that you were in that ended in 2014; he was emotionally abusive and you wouldn't advocate for yourself. But as you begin your strength training journey, we see you come into your own and start to use your voice.

Part of the reason I was so trapped in a dieting and weight loss mindset was that I was really focused on what everyone else wanted, what everyone else was telling me to do. My father was an alcoholic, and the basic psychology of that is, as a matter of your own safety, you have to maintain focus outside of yourself and on what someone else is doing. So when a man comes along who has abusive tendencies, my reflex is to try and manage my feelings, just as I do with dieting, just as I do at work. I'm trying to keep everyone else happy and not thinking about how I feel, because my operative way in the world is to forget how I'm feeling.

Running emphasized this, because at the time, the narrative around exercise in general, but especially cardio, was that it can help you transcend your pain and push down your feelings. It really encourages denial of feelings. When it came time to lift weights, [I learned that] you do one rep of a squat or a deadlift or whatever, and then you ask yourself, How did that feel? Was it hard? Did your form feel off? Did anything hurt or did it feel good? You have to incrementally check in with yourself.

The practice of this helped me develop a practice of noticing how I felt. And it caused me to start noticing my feelings in other in other realms of my life, like how I felt in like a conversation with my boss or my boyfriend. It helped me build this reflex that I'd never had.

Lead collage: Sarah Oliver

This article originally appeared on Harper'sBazaar.com

Also read: Turns out, the best part of the workout is the people