Exploring the allure (and perils) of trading the conventional life for new adventures and experiences

Sophie Elmhirst follows the adventure of an intrepid couple who left their daily life behind for open waters and new horizons.

On holiday in Morocco in my twenties, escaping a job I didn’t like, I went hiking in the mountains. My days at home were spent in front of a computer performing almost entirely meaningless tasks. Up there, under a stark blue sky, sleeping in a freezing hut, I imagined I would finally figure it all out and correct the wayward, stop-start trajectory that was apparently my life. Going away was a way of getting away, but it was also a pursuit of fantasy. This is so often the lure of travel: that we might be someone different—even someone better—somewhere else. Around that time, I was on a strict diet of escapist literature, and I was looking for tips. Top of the pile was the American naturalist Henry David Thoreau’s seminal book Walden (subtitled Life in the Woods in the 1854 first edition). Thoreau spent two years living in a cabin in the woods near Concord, Massachusetts, because, as he put it, "I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived".

By his reckoning, Thoreau wasn’t abandoning life so much as fashioning a new model: one defined by simplicity and self-reliance, a total immersion in nature. He wanted to escape the petty distractions of society, to strip himself of all unnecessary luxury. Pare it all back, live in nature, embrace solitude and, by his logic, you’d discover the fundamentals of existence. He’d be able, finally, "to suck the marrow out of life". It was convincing to me at the time: get away from everything (and everyone) and perhaps I’d finally feel a little more alive.

That urge to flee was the first thing that drew me to the story of Maurice and Maralyn Bailey, a young married couple from Derby, whose extraordinary story is the subject of my first book, Maurice and Maralyn: A Whale, a Shipwreck, a Love Story. In 1972, the Baileys decided to abandon their jobs and conventional lives, sell their home and embark on a long voyage on their small boat. Their plan was to sail around the world and start a new life in New Zealand. For Maurice, in particular, their departure felt seminal. Any act of migration contains a dual force: what someone is leaving behind, and what they are going towards—or, at least, what they imagine they’re going towards.

Maurice believed leaving England would relieve him of his former self: a lonely, awkward young man who had survived an affectionless childhood. Much like Thoreau, he wanted to abandon the claustrophobic conventions of society and, in his case, suburban life: the painfully slow accrual of wealth and status, the obsession with material goods, the endless mowing of lawns. Maurice—like Thoreau—wanted to live in a different and more essential way, detached from human civilisation. Thoreau sought his personal freedom in the woods; for Maurice, it was the ocean.

A few months into their voyage, in the middle of the Pacific, Maurice and Maralyn’s boat was hit by a sperm whale and sank. The couple were cast adrift on a small inflatable raft and dinghy for nearly four months, forced to kill and eat turtles, birds, and sharks in order to survive. They had no radio transmitter, no means of contacting anyone. They were completely—purely—alone. The risk of such individualistic freedom-seeking was clear. Maurice might have craved the simplicity and beauty of nature, but these were his human projections: nature didn’t have much thought for him. Adrift in the middle of the ocean, the place that had once represented the truest form of existence now looked more like a fast track to annihilation.

Maurice and Maralyn did survive; I won’t give away how. Let’s just say that their reliance on each other was fundamental. In difficulty, Maurice quickly came up against his own limits and fell into despair. The fantasy he’d imagined of their escape had disintegrated. We can escape almost everything, it turns out, except the inner workings of our minds. If he’d been alone, Maurice said afterwards, he knew he would have given up. It was Maralyn—pragmatic, optimistic, undaunted—who kept him sane and alive. The thing Maurice had most craved, the absence of civilisation, was the very thing that nearly killed him. Revealed instead, lost in the middle of the ocean, was the necessity of other people—or just one other person—who can free you from yourself.

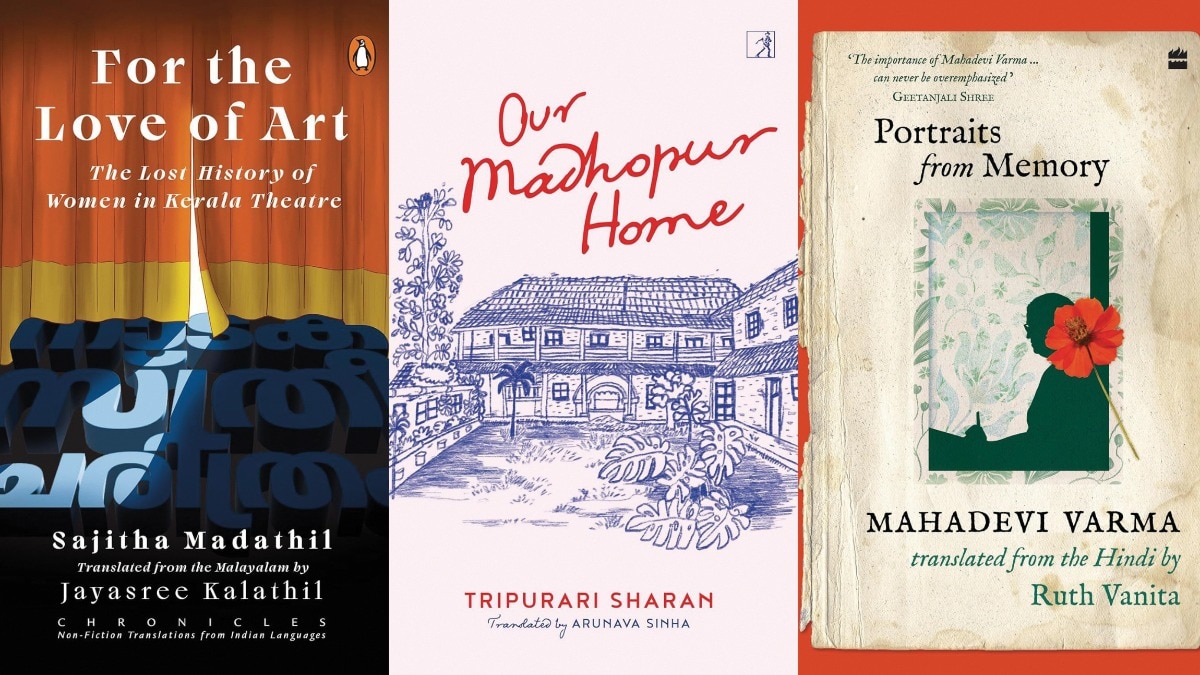

‘Maurice and Maralyn: A Whale, a Shipwreck, a Love Story’ by Sophie Elmhirst is out on February 29.

This piece originally appeared in the February/March 2024 print edition of Harper's Bazaar UK.

Photo credits: https://paradise.docastaway.com/maurice-maralyn-bailey/