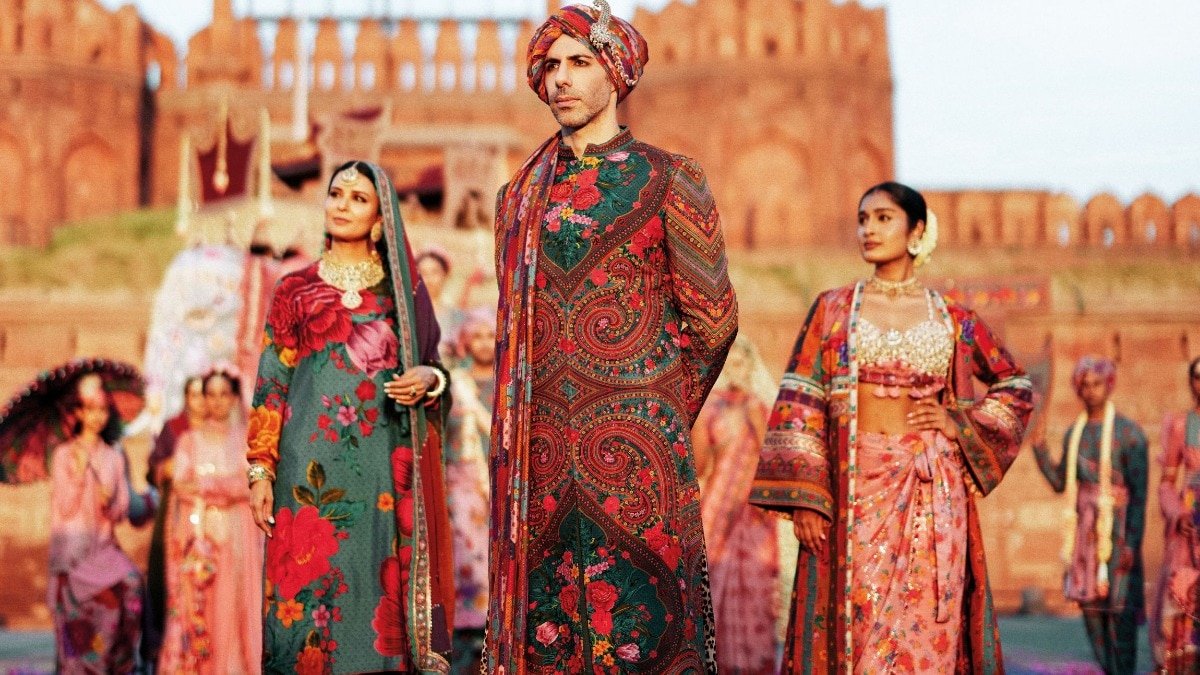

How Fabindia put Indian craftsmanship on the global fashion map

Bazaar discovers how the brand, which has been in the business for over 60 years, evolved into a global icon.

A stitch in time, they say, can save not only a fabric from fraying but also protect an entire legacy of traditional craftsmanship. In its six decades of designing home products and garments for women, men, and children, Fabindia has—perhaps inadvertently—not only preserved the many crafts from across the country, but helped build an aura of ‘cool’ around Indian aesthetic. Much before terms like homegrown, handmade, and natural became the staples of fashion, the brand had already begun to foster the many, nuanced artforms from across the country. And to its credit, it married two disparate worlds, of luxury and rootedness, into a singular identity. Bazaar had an exclusive conversation with its director, Charu Sharma, to discover how it grew into a household name.

Harper’s Bazaar: Do tell us about how Fabindia came into existence.

Charu Sharma: In 1960, John Bissell (an American textile businessman) set up Fabindia out of two small rooms in Golf Links, Delhi, as an export company for home furnishing, floor coverings, and linen. He had a particular love for Indian textiles... John had previously worked as an advisor to the Handloom and Handicrafts Board, to assist the Government with its design and marketing skills. During his tenure, he was taken in by the outstanding artisan skills, and decided that he wanted to help create a market for the same. With time, the domestic Indian market also began to take an active interest in the brand, because it made products, rooted in local heritage, accessible.

HB: What has been the brand’s resounding philosophy?

CS: More than just a product, Fabindia is about a lifestyle. It’s important to commit to conscious consumption that benefits everyone. We believe in a holistic approach, that can give buyers the opportunity to make beautiful, functional, artisanal products a part of their daily lives.

HB: Tell us about some of the major landmarks over the years...

CS: By the late ’70s, the brand had begun experimenting with kaftans and designs created by the late artist-designer, Riten Mozumdar, but it was the ’80s that heralded a major turning point in the brand’s destiny. We launched our first line of garments around then, and soon, young Indians of that era began to respond to and signal pride in their identity with these designs. This was truly revolutionary, not just for Fabindia, but also for ‘off-the-shelf’ ethnic dressing in the country. While men’s kurtas and Nehru jackets were an instant hit, the breakthrough came with the short jackets and kurtas for women.Then, in 2000, the brand introduced hand-crafted home décor and furniture items, and in 2006, the personal care category was added with authentic products rooted in traditional knowledge. Today, Fabindia has 312 stores across the country, and 14 stores around the world. But, most of all, Fabindia has become a ‘must visit’ for many—from Usher to Julia Roberts, Nobel prize winners Abhijeet Bannerji and Esther Duflo, and many a visiting dignitary. This truly makes us proud.

HB: What crafts have been the mainstay of Fabindia?

CS: There is a significant emphasis on the continued use of traditional materials and techniques while creating a contemporary idiom. We started out sourcing from around Delhi, Rajasthan, and Uttar Pradesh. Over the years, we’ve included the ikat of Odisha and Andhra Pradesh, ajrakh of Gujarat, bagru block prints of Rajasthan, and chanderi, Maheshwari, and Benarasi weaves in our designs. Many of the clusters that Fabindia has developed over the years have evolved into very active hubs of craft, with the third and fourth generation involved in them. And given how it is practised, this sector allows women to be actively-involved in the creation of a craft-based livelihood. As we encourage women to work from their homes, their engagement has become a central part of the craft process. This is especially true for finishing and surface ornamenting, craft-based skills like chikanari, appliqué, banjara, and a variety of embroideries, where women are the primary artisans. One of our associate companies, Rangasutra, works with over 2,000 women who are also shareholders in the producer company, itself.

HB: What is the biggest need of the artisan, today?

CS: Currently, the largest concern for the artisan is continuity and regular work, timely payments, and access to markets. The need is to keep the cycle of production and demand going. The sudden halt brought about by the lockdown has had a particularly detrimental effect on their livelihoods, and we have witnessed a significant erosion in the use of indigenous materials and locally-available resources. However, there is still hope, as we are gradually seeing a resurgence, and Fabindia’s commitment to the cause remains strong.