How the ‘tacky NRI’ stereotype clashes with a bold new breed of South Asian creatives who are pushing the boundaries

Once dismissed as outdated or over-the-top, the diaspora is now driving a powerful, hybrid cultural movement across art, fashion, and music.

I have started calling my India trips my “NRI Apology tours.” Whenever I’m in Delhi or Mumbai, friends inevitably use their time to cross-examine me about the ever-confounding diaspora in America. I’ve grown used to the questions: “Why do NRIs dress like that? Why do NRIs think of India like it’s the ’70s? Why are NRIs so OTT when they talk about culture?” Before I can sigh and respond with a defensive “Not all NRIs,” my India-based friends will inevitably pull out their phone and present some damning evidence on Instagram, making my rebuttal all the more challenging.

The debate over the “tacky NRI” seems to define the gulf in sensibility between India and the diaspora. When I was growing up in the US, the criticism against the diaspora was focused on the “ABCD”(American Born Confused Desi): Someone who was over-westernised and detached from India. But after India’s global ascendancy in the last few decades, the criticism has shifted towards the “Tacky NRI”: A non-resident Indian who is frozen in time and out of touch with Indian modernity. No matter the criticism, the diaspora is always placed in a subordinate position to the motherland.

For many NRIs, the cultural references, aesthetics, and rituals they cling to aren’t drawn from contemporary India—they’re inherited from the India of their parents or grandparents. What feels reverent or authentic to the diaspora can read as quaint, outdated, or even kitschy to someone in the homeland. Colours, silhouettes, film references, even slang may align more with the India of the 1970s or ’80s than with the hyper-modern, globally networked India of today. That lag isn’t necessarily wilful—it’s the natural result of nostalgia operating across oceans and decades.

Yet, while these disparities in taste are undeniably present, especially at a time of incredible cultural innovation and creativity in India, I believe a notable segment of the diaspora is resisting the “tacky” label. The same conditions that lead to out-dated and theatrical perspectives can also produce the opposite: Challenging, groundbreaking, and globally relevant forms of culture.

Three years ago, the Instagram account DietSabya posted a scathing takedown of NRIs’ tacky taste, electrifying a debate that migrated from the halls of Instagram and niche sub-reddits to coverage in major media publications. Though the post was targeted at my diasporic brethren, it was hard not to be excited by the moment: Here was proper discourse, a moment when contemporary South Asian culture was penetrating mainstream discussion.

I couldn’t argue against DietSabya’s key point: NRIs often present frozen-in-time, kitschy, and maudlin approaches to culture. I was disappointed by how thinskinned the responses within the diaspora were, especially among online creators who felt personally attacked. One influencer argued that these criticisms were comparable to racism, sexism, or mocking someone’s disability. But if I couldn’t argue against DietSabya’s thesis, I had to ask instead why there was such a disparity in taste. And in that why, I saw a powerful cultural counterweight to the tacky NRI emerging in the diaspora.

There is something uncanny in the encounter between the homeland and the diaspora, an observation thinkers from TS Eliot to Homi Bhabha have made before me. Bhabha describes the relationship between the diaspora and the motherland as one of “baffling alikeness and banal divergence,” an experience that is distinctly uncanny. NRIs appear within an Indian context as a type of doubles—almost the same, but not quite; familiar, but slightly different in an unsettled way. When seeing culture reproduced imperfectly in the diaspora, it’s natural to bristle. The uncanny is an unsettling emotional experience, and when I hear my Indian friends talk about NRIs, I hear how disconcerted they are.

I see where they’re coming from. When existing in the context of the motherland, diaspora tributes to Indian culture can sometimes feel out of touch. But I also empathise with the emotional terrain that informs this. So much of the diaspora experience is defined by loss, a dynamic beautifully described in Racial Melancholia, Racial Dissociation by David Eng and Shinhee Han. As the authors emphasise, rupture from the homeland is an existential quality of immigrant experience. Melancholia and loss are the formative cultural experiences of many immigrants; fantasy, exaggeration, and attempts at rebuilding what’s lost appear as the solutions. It’s no wonder that longing and over-sentimentality are core conditions of a lot of diasporic expressions. What might appear over-the-top and overly emotional comes from an attempt to process a deep sense of mourning, both from where we come from and where we’ve landed.

Also, responding to a feeling of invisibility and marginality in American popular culture, social media has become the major centre of gravity for Indian identity in the US. Platforms like Instagram and TikTok have seen doubledigit growth in South Asian American creator accounts since 2020. The nature of platforms like Instagram is to serve the algorithm, to produce the most relatable and wide-reaching forms of culture to reach a mass audience. This was a dynamic that the scholar Vijay Prashad presciently described over two decades ago, well before the advent of social media. In his early work, he described how American multiculturalism was rooted in consumerism. When immigrant communities were invited to present their culture, it was always in the most consumable ways that met with American market logic (think mangoes, marigolds, and mehendi). In the social media era, years removed from these writings, we are expected to present ourselves as consumer objects for wider audiences. It’s no wonder that NRIs, filling a major representational gap online, appear as flat, stereotyped, and theatrical to Indians who don’t face these questions of visibility.

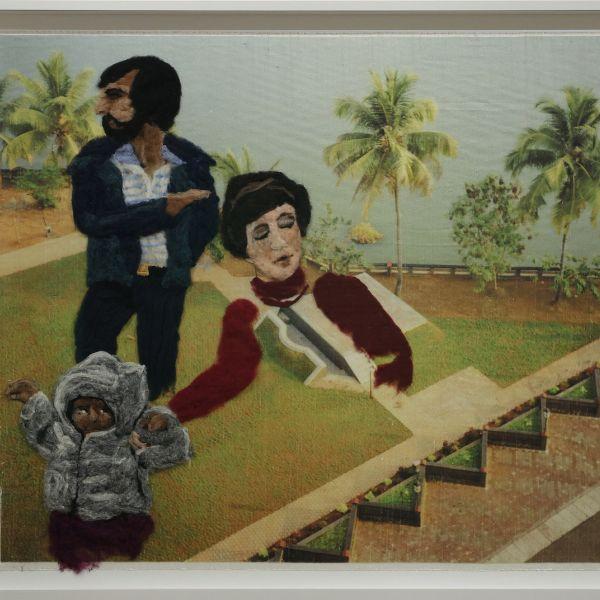

Rajiv Menon photographed in front of the artwork Set Free (2024) by Suchitra Mattai—worn saris, fabric, beaded trim, at his exhibition

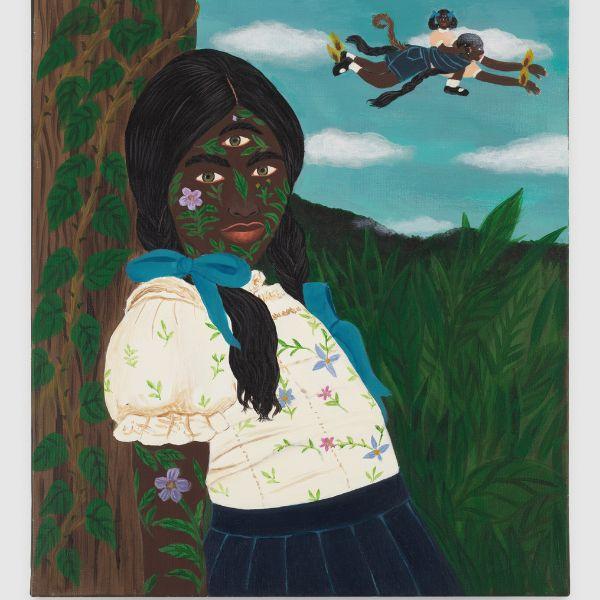

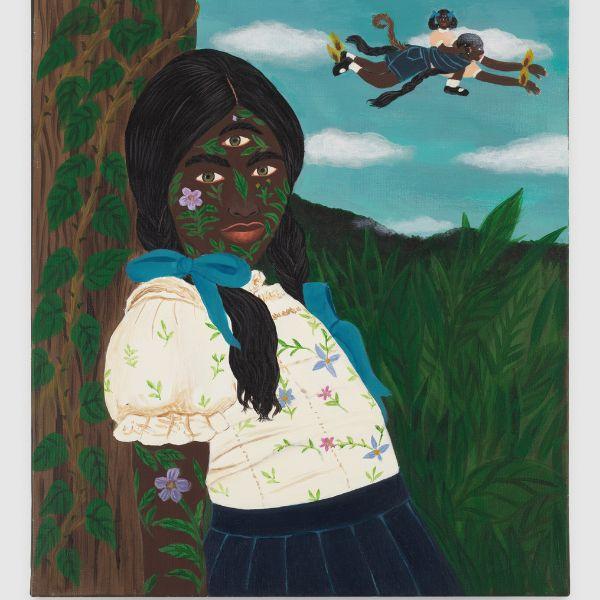

And yet, while I cannot deny the criticisms for many segments of NRI culture, I see the same conditions that produce the “tacky NRI” as producing a powerful counterbalance. My bias as a gallerist is obviously towards art. My recent exhibition, Non-Residency, at the Jaipur Centre for Art, identifies what I call the “Non-Resident School”: A cohort of artists who thrive in the uncanny, hybrid feeling of non-residency. Unlike the tacky NRI, trying unsuccessfully to reproduce “authenticity,” these artists revel in inauthentic hybridity. Their work is simultaneously shifting the cultural landscapes of India and the West, entering major museum collections worldwide. They are thinking not just about the literal experience of being neither here nor there, but the form and feel of that dynamic. Melissa Joseph, for example, uses felt to evoke the fuzzy sensation of memory; Anoushka Mirchandani creates figures that are simultaneously assimilating and multifaceted, like the diaspora itself. Artists like this produce aesthetics that both feel rooted in questions of belonging and Indianness, but also feel fundamentally global and innovative.

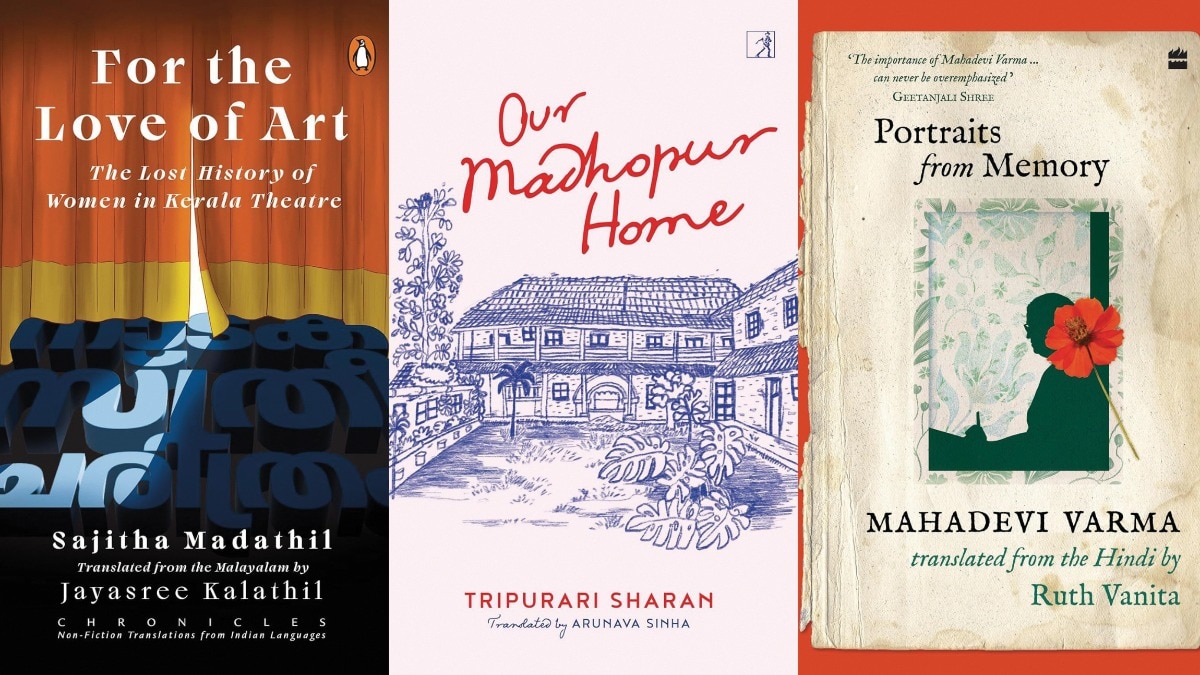

But this is also a larger cultural movement above and beyond art: A Non-Resident New Wave. Literature was arguably an early ground for South Asians transforming global culture. Salman Rushdie, Jhumpa Lahiri, and Kiran Desai paved the way for other mediums to take on this type of global influence. In fashion, the epicentre of DietSabya’s NRIGate, I am struck by labels like Kartik Research and NorBlackNorWhite, who thrive in hybridity and are shifting the way the world dresses. In creative direction, Anita Chhiba of Diet Paratha is altering the way South Asians appear online, not as try-hard like-chasers, but as genuine visionaries and groundbreakers. The list can go on and on, in music, film, and theatre, suggesting a cultural wave that extends to every imaginable medium.

The future possibilities feel most clear when I look to an NRI experience often overlooked in India: That of Indo-Caribbean communities. In Non-Residency at the JCA, artists Suchitra Mattai and Kelly Sinnapah Mary draw upon legacies of migration, indentureship, and cultural mixing to produce aesthetics that feel genuinely fresh and influential. Removed from India by many generations, Indo-Caribbeans are often the first to be labelled inauthentic by Indian or even other more recent diasporic communities. But their global impact is undeniable. Scholar Tejaswini Niranjana writes about this in her ethnographic text Mobilising India, noting that Indo-Caribbean music genres like Chutney, blending local and Indian elements, went on to integrate into wider Caribbean music genres. Both historically and presently, Caribbean genres like Reggae and Soca are deeply influential on the global mainstream, and it is impossible to remove Indian influence from that dynamic. This is the hope I have for the Non-Resident New Wave: Undeniably groundbreaking, influential innovation unconcerned with the shallow politics of authenticity. When I look at the global cultural landscape of today, the spectre of the “tacky NRI” is a distraction; the Non-Resident New Wave is the future.

Lead Image: An untitled artwork, 2025, by Anoushka Mirchandani—oil, oil stick, and oil pastel on canvas

This article first appeared in the August-September 2025 issue of Harper's Bazaar India

Also read: Arundhati Roy on grief, memory, and her most personal book yet

Also read: These South Asian voices are driving a creative revolution in London (and beyond)