'Careless People' is the final girl-boss memoir

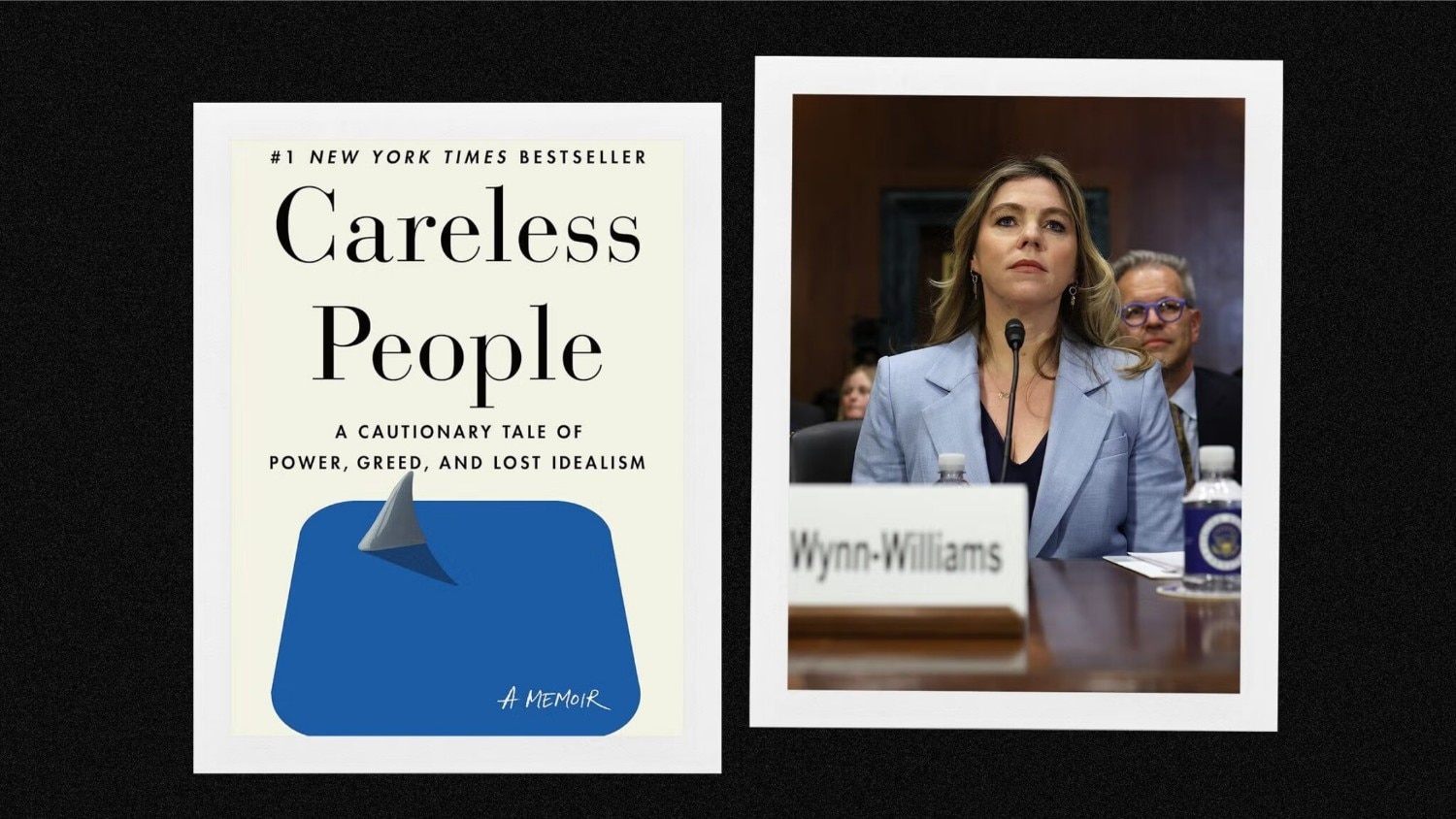

Sarah Wynn-Williams’s tell-all, about the early days of Facebook, reminds us how hard it is to change the world.

The first two chapters of Sarah Wynn-Williams’s memoir, Careless People, an account of her time as head of global public policy for Meta (birth name: Facebook), are full of scenes of her excitedly telling anyone who will listen that the company is on track to “change the world.” At the start of the book, it is 2009 and Wynn-Williams is a New Zealand diplomat at the United Nations. She’s living in Washington, D.C., halfway around the world from her hometown of Christchurch. She is working on global environmental policy. Her job is painstakingly dull. Even though she’s mingling with people from all over, working on projects of great import, she feels the immense frustration that so many do at the start of their careers, when their burning ambition feels constantly undermined by the ways their workplace has always done things.

In between endless meetings, far away from her friends and family, in a city that “still felt foreign” to her, Wynn-Williams begins to understand the power of Facebook. She uses the platform in all the ways we have become comfortable with: keeping track of birthdays, life milestones, and general family news. But she understands its true potential when the platform becomes the only place where she can get real-time information about the fate of her sister, who is trapped in the devastating 2011 earthquake that leveled Christchurch. She evangelizes Facebook to anyone who will listen, touting its power to transform the way we connect with one another and our lives. Her zeal leads her to pitch herself to the company as a potential global public-policy head, though, in her accounting, the company is so new that it doesn’t even really understand why it might need someone in that position.

What follows is a history of the rise of Facebook, from a woman who was there to witness and help facilitate much of it. It’s a history of the past quarter century of life on Earth, a book that succinctly sums up how we find ourselves in 2025 with a tech oligarchy determining much of the planet’s fate and a seemingly cheerful mass capitulation to widespread, continual surveillance and personal data collection.

Still, in those headier, more optimistic days, there were moments of levity to find in it all. The opening chapters are full of anecdotes about the silliness of working for a quickly growing tech behemoth. On her first day on the job in 2011, Wynn-Williams forgets to bring her laptop, because at her previous job, internet access was an afterthought. There she is embarrassing herself with a social gaffe in front of Sheryl Sandberg, then COO of Facebook and later the author of Lean In. It’s the kind of relatable millennial work content that would fill an episode of The Mindy Project or 30 Rock or Parks and Recreation—all those comedies of labour and femininity that defined the 2010s.

There’s also some good petty observational material, like a delicious description of what it’s like to be at Davos: “Around this dull Swiss town, the World Economic Forum has constructed a byzantine social structure where they control the minimal resources available. These are then dished out by their grace and favour according to status. Everything at Davos–every speaking slot, every car pass, every drinks invitation, every meeting room, the distance you sit at dinner from the front table–is distributed according to social status. … The narcissism of small differences … Maybe that’s why they all seem to love this place. … [It’s] a chance for them to measure themselves not just against their own industry but across business, politics, entertainment, and media. A bunch of the richest people in the world.”

Wynn-Williams is good at finding the comedy in all of it. Her time in Davos ends with a high-ranking Facebook exec, former Republican party operative (and Sandberg's ex) Joel Kaplan, blaming Wynn-Williams for losing his cowboy-inspired snow boots. He wore them to Davos to prove he wasn’t a member of the liberal global elite. But, as he tells Wynn-Williams, “there’s a bunch of people I know here.” When he can’t find his footwear, he sends a group email that contains only one line: “SWW lost my sweet boots.”

Soon, though, the book takes a darker turn. At a certain point, Facebook execs, aware of the company’s fast-ascending profile, search for a cause to rally behind to show that the network can be used for good. Kaplan suggests the U.S. Army. When Wynn-Williams points out that the American military may not be universally beloved across the globe, her colleagues look at her blankly. Despite being full of graduates from the “best” colleges, this aspect of American foreign policy seemingly hasn’t occurred to any of them. “Don’t you love our troops, Sarah?” Kaplan asks her.

Eventually, there is the suggestion that Facebook could be used as a directory for organ donation. When Wynn-Williams points out the ethical conundrum of this, that it might encourage human trafficking, Sheryl Sandberg becomes angry. “Do you mean to tell me that if my four-year-old was dying and the only thing that would save her was a new kidney, that I couldn’t fly to Mexico and get one and put it in my handbag?” Wynn-Williams recalls her boss asking. In Wynn-Williams’s telling, Sandberg, who would become famous for encouraging women to “lean in,” winds up throwing her under the bus and pinning the idea on her, and Mark Zuckerberg immediately shoots it down.

“[The engineers] don’t think Facebook should be using the platform to push people to do anything—donate their organs, vote, eat more vegetables, floss, adopt stray puppies, anything,” Wynn-Williams writes. “I agree with them. If we get into the business of advocacy, we’ll have to make all sorts of choices about what causes Facebook does and does not support. We’ll very quickly find ourselves in a world of impossible choices.”

Careless People would have made a splash whenever it was published, but it got a super boost of publicity when Meta took legal action and won the right to enforce a gag order against Wynn-Williams. She is barred from personally promoting the book in the U.S., but that action has made it a hot commodity; it hit number one on the New York Times bestseller list the week it debuted, and Wynn-Williams has been giving interviews in Australia and her native New Zealand.

I’m about the same age as Wynn-Williams and entered the workforce around the same time that she did. Back then, people used to say they wanted to change the world. Nearly every place I worked at in my 20s had this mantra around it, even when it was paying me and everyone who worked there $26,000 a year. People said it earnestly, without embarrassment or any hint of irony; it was something it was okay to openly aspire to if you were of the generation who were teenagers just before 9/11. I don’t think you could understand it if you were born anytime after that period. Back then, it was understood that the world’s problems were fixable and could be solved in the near term through hard work and philanthropy. Changing the world came with no downside, no period of social ostracism or loneliness. If you were thinking in the right way, success was all but guaranteed.

When you said you wanted to change the world, it was around big, vague catchphrases that glossed over inequities, history, and hurt. End racism. Feed the hungry. Peace in the Middle East. A Black president. A woman president. What these things might materially mean—whose rights or pains or frustrations might have to be squelched or ignored; what structures of greed or complacency might have to remain in place to get there—was deemed too negative to think about, part of the language of people who did not want to actually do anything, who maybe did not really want to change the world.

That phrase is pretty much meaningless now, as we sit in the midst of multiple apocalypses. But my most toxic millennial trait is that I wish that it could come back into favour, even just for a bit. Whatever is coming our way in this strange new future that companies like Meta have helped build, we’re going to need dogged optimism and a kind of blind faith to fix it.

Lead image: Hearst Owned

This article originally appeared on Harper'sBazaar.com

Also read: Must-read books to add to your reading list this month

Also read: If you love a good scare, add these horror films to your watchlist